The Fed’s policy arm, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), meets on Tuesday and Wednesday and is widely expected to keep the fed funds target range unchanged at 5.25 – 5.50%. Since March, 2022 the Fed has raised rates at every meeting except the meeting before last in June.

With the Fed raising rates as sharply as it has in decades and the yield curve decidedly inverted (short-term rates higher than long-term), often seen as a precursor to a recession, we are often asked why we went against the broad consensus going into 2022 and didn’t call for an imminent recession and still aren’t.

It is a practically iron law of economics that higher interest rates slow economic growth, and historically has usually slowed the economy enough to push it into a recession when the Fed is pumping the brakes. But even if economic growth slows, it could simply lead to slower growth, not an outright contraction, and we saw several mitigating factors this time around that are largely still in play.

Stay on Top of Market Trends

The Carson Investment Research newsletter offers up-to-date market news, analysis and insights. Subscribe today!

"*" indicates required fields

Here are 10 reasons things have, in fact, been different this time so far.

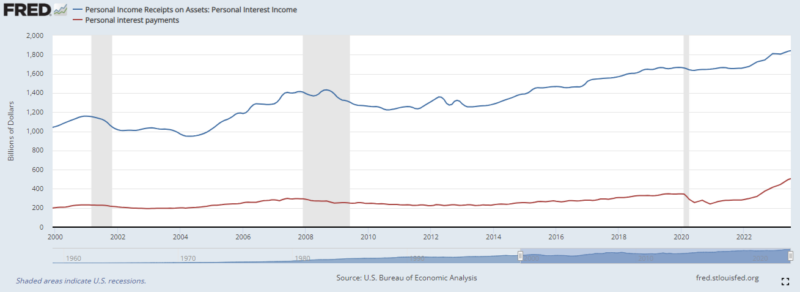

- It’s not all downside. Higher rates are positive for savers and with the population skewing older and wealthier over time that effect has increased. Since February 2020, Personal interest income has increased by $182 billion while personal interest expenses have increased $162 billion (through July 2023).

- Being able to borrow long-term at very low rates over the last decade is blunting some of the effect of higher rates. Higher mortgage rates, for example, are having an impact, but many current mortgages are still at historically low rates. The combination has had some negative economic impact, but not as much as higher rates might have in the past. This is true for many corporations as well—many borrowed aggressively when long-term rates were historically low.

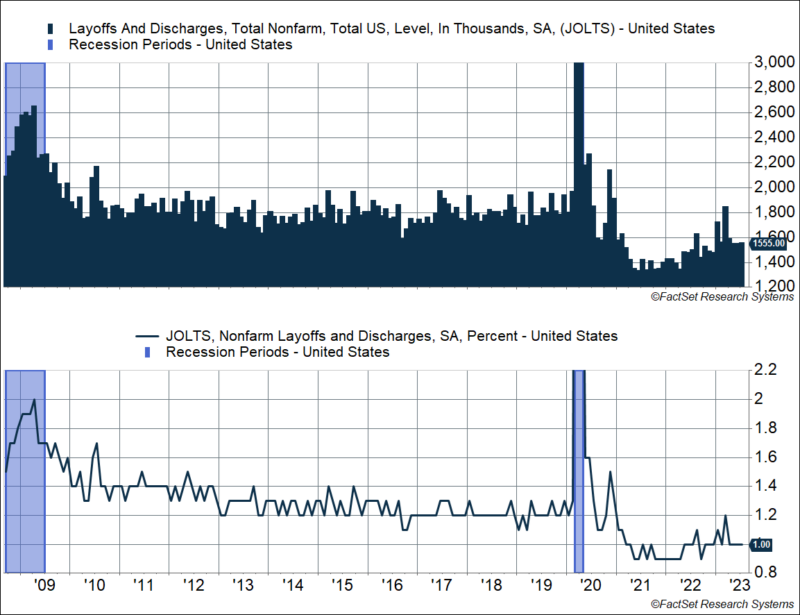

- Employers are reluctant to let employees go after the challenges of the “great resignation,” making the job market more resilient. Layoffs, as a percent of the employed workforce, is at 1%, versus 1.2% before the pandemic.

- The residual effect of COVID-related stimulus has lasted longer than expected. This trend is likely on its last legs. But there has been some new infrastructure and business-oriented legislation (the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, the CHIPS and Science Act and the Inflation Reduction Act) that are providing a modest offset.

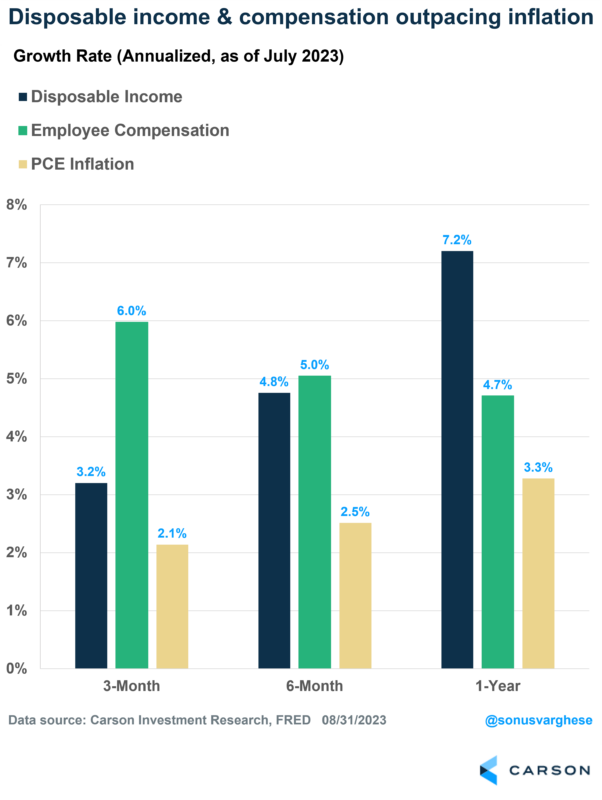

- Post-COVID pent-up demand is still in play. This is likely fading as well, but the increase in demand for services (think vacations, entertainment, and dining out) is still being felt. Consumption has been supported by strong income growth, on the back of strong employment gains and wage growth. Receding inflation has also boosted real incomes.

- Inflation has been hot and labor markets tight, but the economy, while doing well over the last several quarters compared to history, is not overheating. As a result, the Fed’s aim remains slowing inflation but not necessarily breaking the economy, which far from being irrationally exuberant appears to be irrationally sullen.

- The stock market and housing prices have been resilient, leaving wealthier consumers very comfortable with their balance sheet as a complement to a strong job market. This is probably why the savings rate is not rising back to pre-pandemic levels. As Neil Dutta from Renaissance Macro put it: “If my stock portfolio is rising and home prices are climbing, I don’t feel like I need to be saving as much.”

- The normalization of rates after a long period of suppressed low rates may be less of a shock than a jump in rates from a more normal historical level.

- There may be some structural changes in how businesses operate that may make them less dependent on short-term borrowing, both slowing and limiting the impact of higher rates.

- Economic policy acts at long and variable lags, as Milton Friedman famously argued based on his extensive research into rate hiking cycles, so this cycle the lag of the impact may just be longer. “Long and variable lags” may be the phrase everyone loves to hate right now following the debacle of “transitory” higher inflation. But the idea is not dead yet. What’s the statute of limitations? We’ll have to be empirical about it. If the Fed starts lowering rates at some point simply to normalize them rather than to jumpstart a flailing economy, we will have reached it, and inflation pulling back.

The way we would put it, a Fed hiking cycle is often enough of a shock to the economy that it causes a recession in itself. Higher rates do make us more vulnerable to an additional shock that could cause a recession, but after more than a year of an aggressive hiking cycle, they haven’t been enough of an adverse shock to offset a positive backdrop, in contrast to history. Due to various circumstances, the economy just had too much going for it. It still does, at least for now.

1906085-0923-A