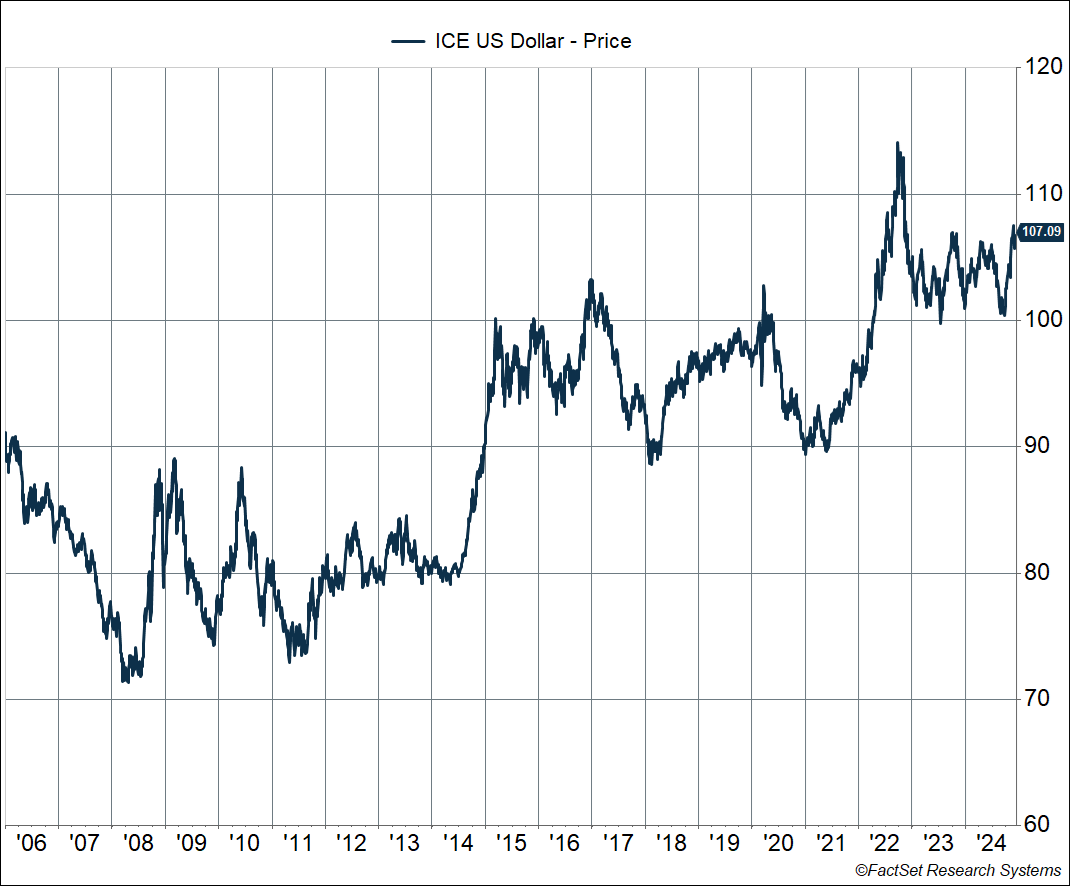

The dollar has been on a tear since the end of September, and especially post-election. It took a bit of a breather over the Thanksgiving week but swung up again over the last couple of weeks. The dollar is now up over 6% since the end of September (through December 12th). Just before the Thanksgiving break, I wrote a piece on why the dollar was surging and the risks posed by a strong dollar, including headwinds for US manufacturing, US company earnings, and international equity investors (in USD terms). Looking at the chart below, the dollar is clearly elevated relative to the last decade (when the dollar had already strengthened relative to the mid-2000s and early 2010s).

A big driver of the dollar is relative growth rates between the US and everyone else, and US economic data has come in strong over the last few months. Expectation for stronger economic growth in the US means interest rates are likely to remain high, with the Fed keeping policy rates higher relative to other countries. That means interest rate differentials are likely to run high, driving the dollar higher.

So, the outlook for the dollar really depends on how you think the US economy will do relative to everyone else.

Outlook for Global Growth Ex US Is Very Different From 2017

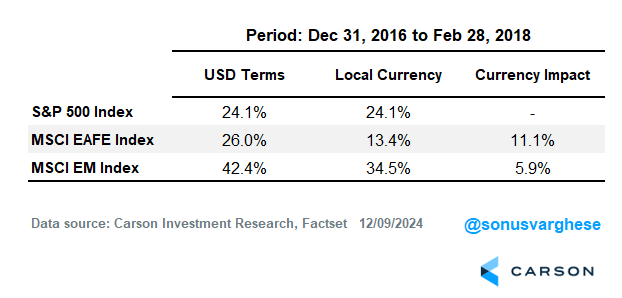

The dollar plunged about 14% in 2017 through February 2018, Trump’s first year in office. But back then, the global economy was recovering. Europe showed signs of growth after several years mired in debt crises, and China was re-stimulating its economy after the weakness in 2015-2016. Note that this also helped international equities outperform US equities in 2017 (through Feb 2018). As I’ve pointed out previously, Emerging Market (EM) returns are helped by a weaker dollar even in local currency terms. This is because a lot of EM companies borrow in USD, and so a weaker dollar helps their balance sheets.

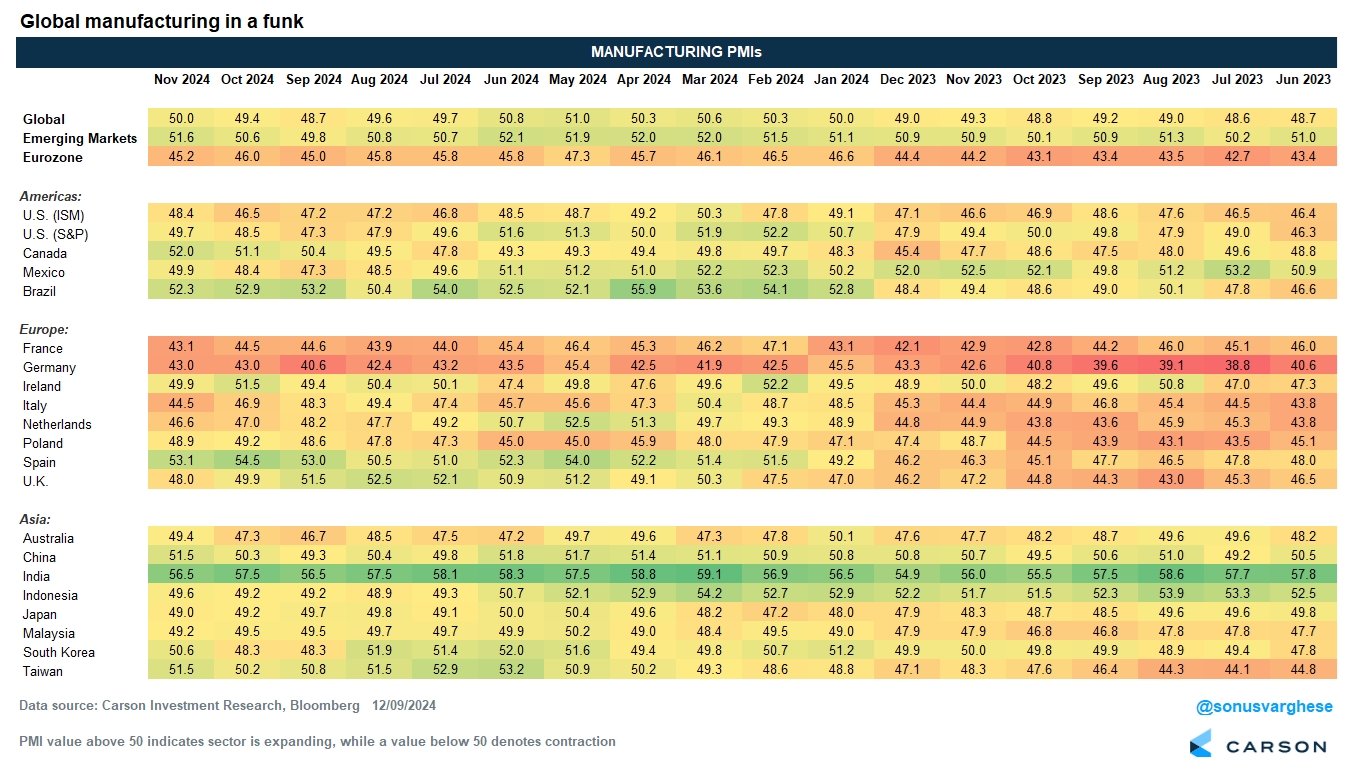

The situation is very different now. Global manufacturing is in a funk as we enter 2025. US manufacturing PMI woes are well known, but the one advantage for the US is that manufacturing is not a big part of the economy. So, a slowdown in manufacturing, or even contraction, is not enough to push the economy into recession. However, that’s not true outside the US, especially for countries like Germany and South Korea. As of November, 13 of 18 major countries across the globe had manufacturing PMIs below 50, indicating their respective manufacturing sectors are contracting — including powerhouses like Germany, France, Japan, and even Mexico. India is a notable exception, with a manufacturing PMI of 56.5, but then India is not known for its manufacturing prowess.

What’s the Problem with Germany? (Hint: It’s China)

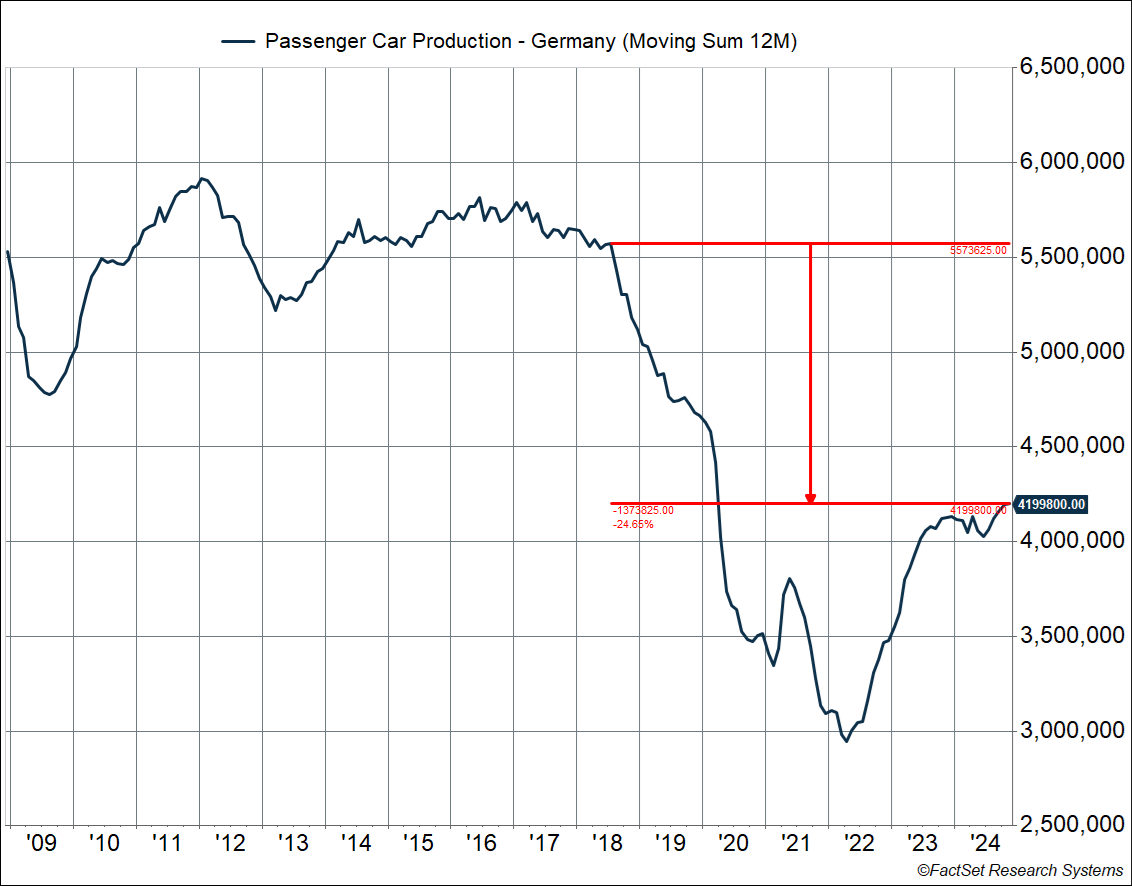

As you may have noticed above, Germany’s PMI of 43.0 is amongst the worst of the lot. Industrial production in Germany has completely collapsed. It’s down 2.7% year to date (through October) and down a massive 15% from the end of 2018. Note that 40% of Germany’s economy relies on exports (and hence, manufacturing), versus just 7% for the US (for goods exports). The big story is really the collapse in German auto production. Germany used to produce on average 5.6 million vehicles a year between 2014 – 2018. That collapsed in late 2018, and through the pandemic. Despite a recovery in 2023, production has now stagnated to around 4.2 million vehicles — a whopping 25% below the 2014-2018 average.

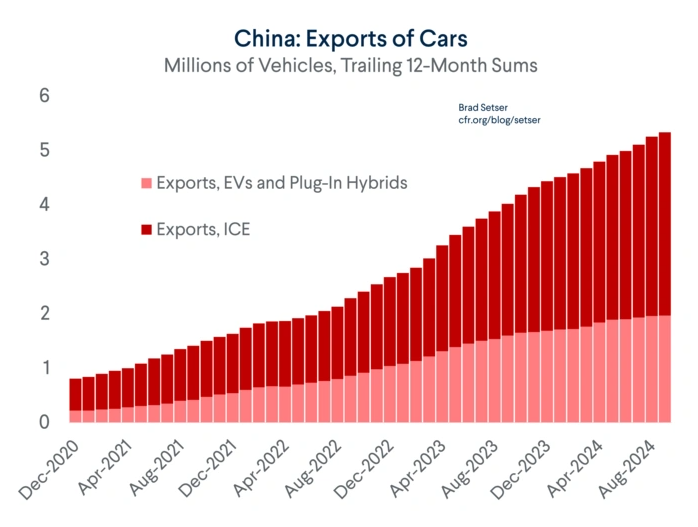

A big reason for this is the takeover of global auto manufacturing by China. Brad Setser (an economist at the Council of Foreign Relations) recently wrote about how China became the world’s largest car exporter, with 6 million cars exported in 2024. Five years ago, that number was less than 1 million. China is now on track to export over 5 million vehicles on “net” in in 2024 (exports minus imports). Back in 2020, it was a net importer of vehicles!

China now has enormous capacity to produce cars — over 40 million internal combustion engine (ICE) cars a year, and about 20 million electric vehicles (EVs) by the end of 2024. This means China has the amazing capacity to supply over half the global market for cars. Globally, about 90 million cars are sold a year.

Of course, as Setser points out, China has nothing close to this level of internal demand. The internal market is about 25 million cars, and it’s not growing. Interestingly, domestic EV sales are rising rapidly (expected over 15 million next year). And as a result, ICE vehicle capacity is geared to exports — especially to Europe and other EMs (US and India are notable exceptions because of tariffs imposed on Chinese vehicles). And China’s massive overcapacity is a revolution for the global manufacturing and auto industry. China’s also added shipyard capacity for exports.

This has all come on the back of massive subsidies from the Chinese state, including for downstream manufacturers like battery and chemical industries (along with cheap steel). This gave Chinese car companies a huge leg up over Western companies that don’t benefit from subsidies. These subsides also go towards building out industrial robots. An interesting story is that Volkswagen apparently uses only one German robot in its latest Chinese factory. The other 1,074 robots were made in Shanghai. I should note that China hands out subsidies dime a dozen, but the competition for those is fierce. China has about 100 different EV companies. But a true market economy wouldn’t be able to support them all. It’s generous government funding that provides crucial support to all of them, allowing them to scale up.

Stay on Top of Market Trends

The Carson Investment Research newsletter offers up-to-date market news, analysis and insights. Subscribe today!

"*" indicates required fields

What does this have to do with the dollar? Well, if global manufacturing remains in a funk due to Chinese overcapacity, along with continued subsidies for the Chinese industrial sector, manufacturing-dependent economies in particular will continue to struggle. This means global central banks are likely to ease rates more rapidly than the US. That’s going to put upward pressure on the dollar.

Global Political Dysfunction Is Another Factor

On top of slowing growth abroad, global crises mean there’re even more potential tailwinds for the dollar. There’re the events in the Middle East (Syria), but what happened in South Korea and France is perhaps more relevant.

South Korea’s President imposed martial law last week, only to withdraw it a few hours later. But it’s plunged the country into political chaos. France’s government, led by Michel Barnier, collapsed last week, as left-wing and far right-wing parties voted for a no-confidence motion. Their main gripe was a proposed budget that looked to rein in the deficit, with spending cuts and tax hikes.

The common theme was that these events arose amid political dysfunction, both in South Korea and France. But the problem is that political dysfunction in these countries (and even in Germany) is not a scenario for economic growth to pick up. In fact, in Europe, EU rules mean we may even see the straight jacket of government austerity imposed on budgets, which is not what you need amid slowing growth prospects. This could result in more political upheaval as left- or right-wing governments gain power.

Keep in mind that all this is happening while the US economy continues to remain solid and likely to be supported by fiscal policy over the next couple of years. Again, this is a scenario under which the dollar strengthens.

But What Exactly Does Trump Want?

President-elect Trump clearly wants to revive American manufacturing and one pathway to that is a weaker dollar. He’s said that that US has a “big currency problem,” which reflects what you saw in the first chart of this piece — the dollar is near its strongest level in a long time. In fact, in real terms the dollar has been stronger than now in only four months since the 1985 Plaza Accord. That was when the leading nations got together and agreed to devalue the dollar. Interesting side bar, Trump bought the Plaza hotel, where the accord was signed, in 1988. (He sold at a loss in 1995).

Yet, proposed policies inadvertently lead to a stronger dollar. In my prior blog, I noted how expected tariffs are being front-run by a strengthening dollar. Policies to boost US growth (even as other countries struggle) is another dollar tailwind.

Trump also wants to protect the reserve currency status of the dollar — including threatening tariffs against the BRICS countries if they move away from the dollar. For one thing foreigners don’t trade in USD out of charity. It’s because they sell a lot of stuff to Americans and get USD in return. Those USD are used to buy US assets. In a sense, they have no choice, given their own policies to run trade surpluses. If the US wants to revive domestic manufacturing and reduce the massive trade deficit (by boosting exports), that implies the rest of the world will receive fewer dollars on net, as they’ll be using the USD they receive for selling goods to us to turn around and buy American manufactured goods. You can’t really have it both ways. Ultimately, the administration will have to choose which direction to go in, and that’s really the question for 2025. And that will potentially have big implications for the dollar, and probably other assets tied to the dollar as well.

For more content by Sonu Varghese, VP, Global Macro Strategist click here.

02551958-1224-A