Carson Investment Research just released our 2024 Market Outlook, “Seeing Eye to Eye”. While our view on the economy leads us to favor stocks over bonds in 2024, we believe that bonds are poised to return to their traditional roles as a portfolio stabilizer and source of diversification. One traditional role they’re already playing again: bonds are now once again acting as a strong source of income, even at shorter maturities.

Many investors’ fixed income holdings still heavily favor short- or ultra-short maturity bonds or cash-like vehicles. According to quarterly Federal Reserve (Fed) data, money market assets were over $6 trillion at the end of Q3 2023, roughly double what they averaged from 2011 to 2017. We believe 2024 may see substantial in-flows to bonds as market participants anticipate the Fed beginning to lower short-term rates, which may help anchor yields despite some likely continued volatility.

Our outlook for the total return of the Bloomberg US Aggregate Bond Index (Agg) in 2024 is 4-6%, based on a yield of 4.65% as of January 16 and a stable yield outlook overall given our expected path for inflation, the Fed, and the economy. It is possible that some bond gains were pulled forward when yields plunged in the fourth quarter of 2023, but we still maintain a favorable outlook.

Stay on Top of Market Trends

The Carson Investment Research newsletter offers up-to-date market news, analysis and insights. Subscribe today!

"*" indicates required fields

While our outlook is for a favorable economic backdrop for credit-sensitive bonds, we’ve grown somewhat more cautious more recently only because credit spreads are already tight and we see more upside for equities, including some pockets of attractive valuations. We recently raised the credit quality of our bond allocation while still maintaining some overweight exposure to credit-sensitive bonds.

LONGER-TERM YIELDS MAY NOT FOLLOW SHORT-TERM YIELDS LOWER

There are basically two competing forces on yields in the coming year: the typical pattern of falling short-term yields from prospective Fed rate cuts pulling longer-term yields with them. That force is opposed by some likely normalization of a still heavily inverted yield curve, which would make long-term yields less responsive, or even unresponsive, to short-term yield changes, especially in the absence of a recession.

Since 1963, the three-month Treasury yield and the 10-year have moved in the same direction, using annual data, 74% of the time and when they have moved in opposite directions, the changes have typically been small. The change also scales nicely in general—larger changes in one means larger changes in the other. On average, the 10-year yield moves 0.5 – 0.6%-points for a 1%-point move in the 3-month yield. From that alone, you would expect four Federal Reserve rate cuts by the end of the year (our current base case as discussed in Sonu Varghese’s recent blog) to lead to about a 0.50%-point decline in the 10-year yield.

On the other side, the yield curve is still very inverted (long-term yields lower than short-term yields). Currently, the 10-year yield is about 1.38%-points below the three-month yield. Historically, on average, it’s 1.32%-points above it. That would mean the 3-month Treasury yield, which runs at about the level of the fed funds rate, would need to fall 1.70%-points, or the equivalent of almost seven cuts, without the 10-year Treasury moving at all to get back to an “average” level of steepness.

Because of that, our base case scenario is relatively stable 10-year yield over the course of the year with a slight downside bias supported by demand depending on the path of rate cuts. But even if yields end near where they began, the path may be somewhat bumpy. Nevertheless, we don’t think the path will be nearly as volatile as 2023 when the 10-year yield finished about where it started, but with giant swings in between.

THE RISK OF SHORT-TERM BONDS

Probably the main bond question we’ve received over the last year is when it’s safe to lengthen the maturity profile of bond holdings and hold a more traditional core bond portfolio again. That question is just as relevant for 2024.

The main risks with short maturity bonds are not so much losses (although they can experience some short-term losses) but that you may have to settle for a lower rate if yields drop (reinvestment risk) and that you lose the added portfolio ballast if equity markets become volatile and bonds return to their role as a diversifier.

At the same time, there are bond features that make core bonds less likely to experience the types of losses they have experienced over the last several years. First, higher yields mean higher coupon payments to offset potential price losses from raising rates, making fixed income more resilient. Over the long run coupon payments are overwhelmingly the main driver of bond returns, not price changes, since every bond’s eventual price at maturity is fixed at the par value of the bond. That’s what makes bonds a “safer” investment. It doesn’t matter what the price is now—you know exactly what the price will be at maturity (outside default risk). In early 2020, the Aggregate Bond Index (Agg)’s yield would have had to climb just 0.2%-points over a year to result in a flat return. Anything more than that would have resulted in a loss. Now it would require a move four to five times as large. (Some of that resilience can also come from the natural price movement toward par over time.)

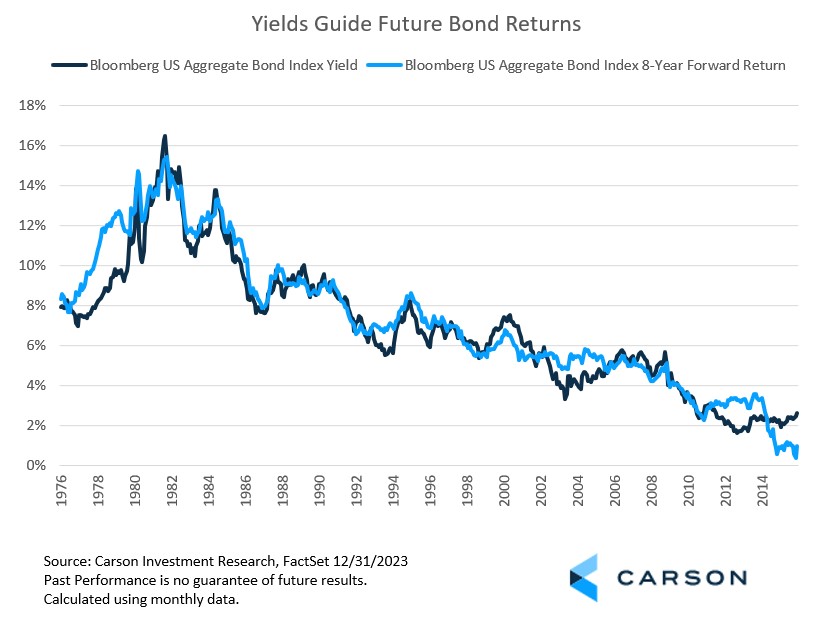

These features of bonds also make the Agg’s yield a strong predictor of returns over the long run. Of course, climbing yields are why bonds have seen losses the last several years, but those bond losses do point to stronger return prospects in the future. As noted above, the yield to maturity for the Agg on January 16 was 4.65%. The average yield from 2010 – 2021 was just 2.34%.

As shown in the chart below, annualized returns for the Agg over the next eight years tracks the yield at the beginning of the period fairly closely, coming within +/- one percentage point annually 74% of the time. By contrast, current short-term bond yields are a weak predictor of future long-term returns because the yield is only good for a short amount of time before the bond needs to be rolled over, and it’s hard to forecast where short-term bonds yield will be in the future, especially as you move further out.

Another way of saying it: Short-term bonds have low short-term return uncertainty but high long-term return uncertainty. Long-term bonds have relatively high short-term return uncertainty but relatively low long-term return uncertainty.

Our recommended maturity profile for bond holdings was quite short at the beginning of 2023. We slowly faded rising rates over the course of the year and moved just short of the Agg toward the end of the year. This final move was based on the historical pattern that intermediate maturity bonds start to outperform ultra-short maturity bonds in the six months before the first rate cut after a hiking cycle. This isn’t surprising, as markets are forward looking. We believe the effect in 2024 may be consistent with the past but somewhat weaker, since many initial cuts historically are in response to an economy entering a recession following Fed overtightening, which is not what we expect to see next year.

02075650-0124-A