We came into 2023 with a view that stocks would rebound quite strongly, and the economy would be able to avoid a recession. As a result, we were overweight stocks over bonds in our tactical portfolios. We continue to maintain this overweight, since we believe equities could see even more gains before the end of the year – we discussed this in our Mid-Year Outlook.

We were in a lonely camp at the beginning of the year (though it’s become less so lately). As a result, we’ve gotten several questions as to what drove our conviction to overweight stocks. Anyone would be lying if they answered they had 100% conviction in any particular view, and in any case, it would be folly to construct a portfolio based on that.

While we look at the macroeconomic data and what markets may be trying to tell us, one thing that is key in anchoring us is our longer-term strategic positioning. This forms the starting point of our tactical views, upon which is layered our current views on the economy, policy, technicals, and valuations. One way to think of it is that the burden of proof to shift away from our long-term views is large.

Using more than one lens

One of my favorite authors in finance is Anti Ilmanen (AQR). In his book “Expected Returns”, he recalled the parable of 6 blind men and the elephant. Each one approached an elephant, hoping to learn much. But each of them only had a narrow perspective. The first felt the Elephant’s side and described the animal as a wall. Another felt the tusk, and though the elephant was like a spear. The third touched the trunk and imagined it to be like a snake. The funniest one in my view was the man who seized the swinging tail and thought the elephant to be like a rope. They all got into bit of a fight after that, with each strong in their own opinions.

The problem was that each one was partially right, but none of them saw the whole picture (or animal in this case).

The same problem can exist in investing. Instead, you need multiple lenses to see the full picture. You cannot rely on any single model, especially since future expected returns are unpredictable, and can vary across time.

For our strategic views, we combine:

- Historical data

- Investing theory, and behavioral explanations

- Discretionary perspectives

These are probably best illustrated with a couple of examples.

Why We Overweight Stocks Over Bonds

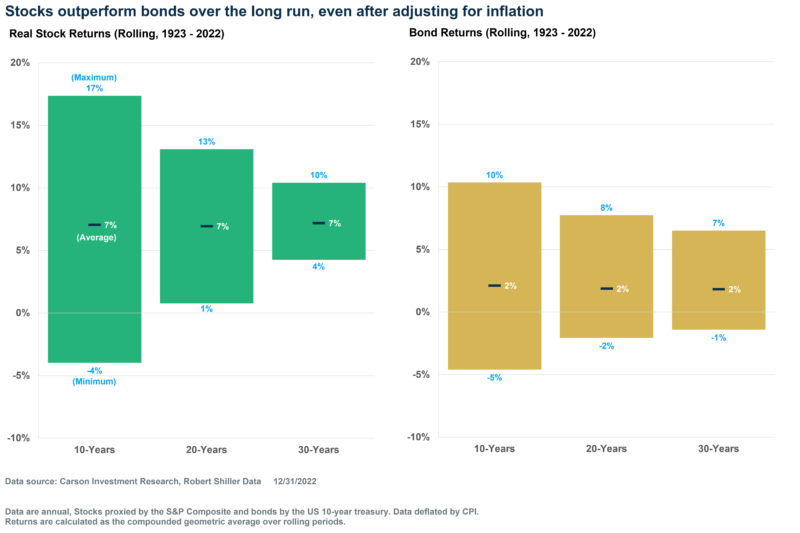

Historical evidence suggests that stocks outperform bonds over the long-term, even after adjusting for inflation. It would be straight-forward to simply overweight stocks on the weight of that evidence. Of course, stocks are riskier as well, and so we should be “rewarded more”.

But why? An important question, because answering that allows for more conviction in our views.

Stay on Top of Market Trends

The Carson Investment Research newsletter offers up-to-date market news, analysis and insights. Subscribe today!

"*" indicates required fields

What’s interesting is that the “equity risk premium” cannot be explained by standard economic models. Historically, this premium. i.e., the difference between equity and “risk-free” cash, has ranged between 4-8%. Economic models say that is simply too high, even after accounting for higher risk.

Professor Jeremy Siegel pointed out in his book, “Stocks for the long run”, that the compounded annual real return on US stocks from 1802-2021 is 6.9% per year, versus 2.5% for treasury bills (after inflation). That’s almost double the growth rate of GDP. In fact, the real return on stocks has been remarkably stable over major sub-periods, and the variability reduces as you extend the time horizon. This may surprise you – after adjusting for inflation, bond returns have similar variability to stocks over long periods of time, and even more so if you extend the time horizon to 30 years.

Behavioral finance explains the equity risk premium via myopic loss aversion and mental accounting. If an investor evaluated their portfolio very often, they’d probably see their investment outperform bonds only about half of the time (even annually, stocks outperform bonds only 65% of the time). That kicks in loss aversion, i.e., losses are valued more than gains. It’s as if people are saying:

“Yes, we get that stocks could go up next year. But it could also go down, and I hate losses. So, I don’t want to invest in stocks. It’s too risky.”

And so, investors require a higher premium to overcome that hurdle. Even worse, loss aversion varies based on prior experience, including gains and losses an investor’s experienced. And typically, investors become even more conservative amid down markets. As Warren Buffet said:

“The stock market is the only place where investors run out of the store during a sale.”

Why We Prefer US Stocks over International Stocks

This is a tough one, especially because we are deeply aware of home-bias. On top of that, international stocks are valued cheaper than US stocks currently, and so it can seem like a straight-forward bet to at least keep international stocks at neutral weight, let alone overweight them. Nevertheless, our discretionary perspectives form our view in this case.

For one thing, US companies are global and capture revenue and profits from across the globe. In fact, 40% of S&P 5000 company revenues come from outside the US.

Going forward, we also believe economic growth will be relatively faster in the US than in other countries. Europe may struggle to cohesively bring together the divergent goals of the northern countries versus their southern neighbors (who must deal with the straight jacket of the euro). The UK looks set to struggle with the consequences of Brexit, and Japan has significant demographic challenges.

We are also cognizant of the growth risk in emerging markets (EM), especially China. Beyond the political risk (which is not insignificant), we also believe emerging markets have economic challenges going forward. The heyday for EM investors was in the 2000s, when a lot of investment in these countries was geared towards satisfying Western demand. That boost can happen only once, and now the question is whether they can grow based on internal consumption. Household share of national income must rise for that to happen, but that involves redistribution – and that’s where the challenge lies.

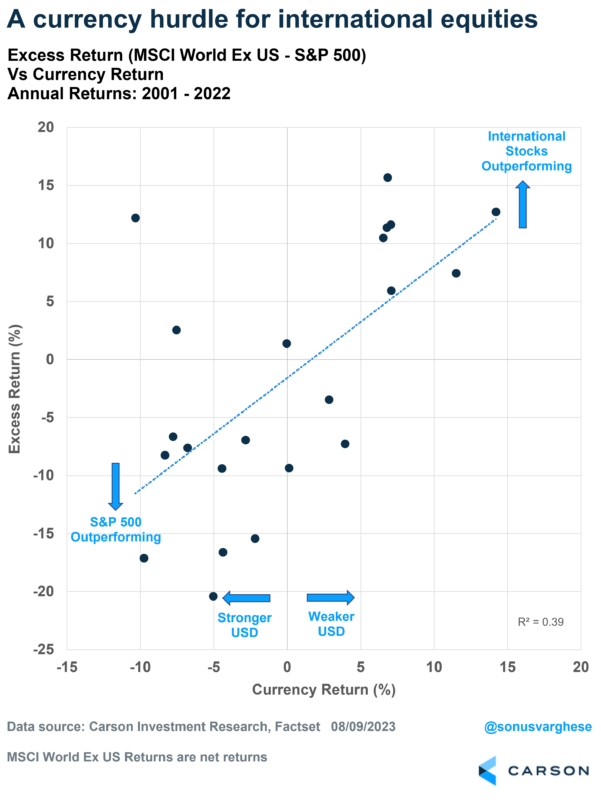

Why does this matter? Relatively stronger economic growth in the US means the US dollar is likely to remain strong for a while, with the Federal Reserve keeping rates higher than what we’ve been used to over the past decade. The US dollar is inversely correlated with international equity returns (denominated in USD), and so a strong dollar could act as a drag on international equity returns.

We could write a lot more on all our views, but this is intended to give you a lens into how we develop our strategic house views. They are a critical anchor for our portfolios. Of course, we realize we could be wrong, and that is why continuously evaluate our views, and update them if necessary.

1862386-0823-A