Carson’s VP, Global Macro Strategist Sonu Varghese and Chief Market Strategist Ryan Detrick spoke with Dr. Jeremy Siegel in our latest Facts versus Feelings podcast, and I couldn’t but help borrow the title of this blog from the title of his must-read book, Stocks for the Long Run. Dr. Siegel has had such a strong influence on the investing landscape that I have no doubt, in my opinion, that every good idea in this blog in some ways has its roots in his work.

One of the aims of our blogs is to share the basic principles of investing that help people avoid the biggest investing mistakes. One of the biggest is selling stocks for the wrong reasons, and the #1 “wrong reason” is poor decisions about market timing. It is perfectly appropriate to choose to limit stock exposure to match one’s risk tolerance. It’s the moves around that risk tolerance where the mistakes happen. We see it every time there’s a frenzy of selling when stocks have sold off. As my colleague Ryan Detrick often repeats, markets are the only place where things go on sale and people run from the store screaming.

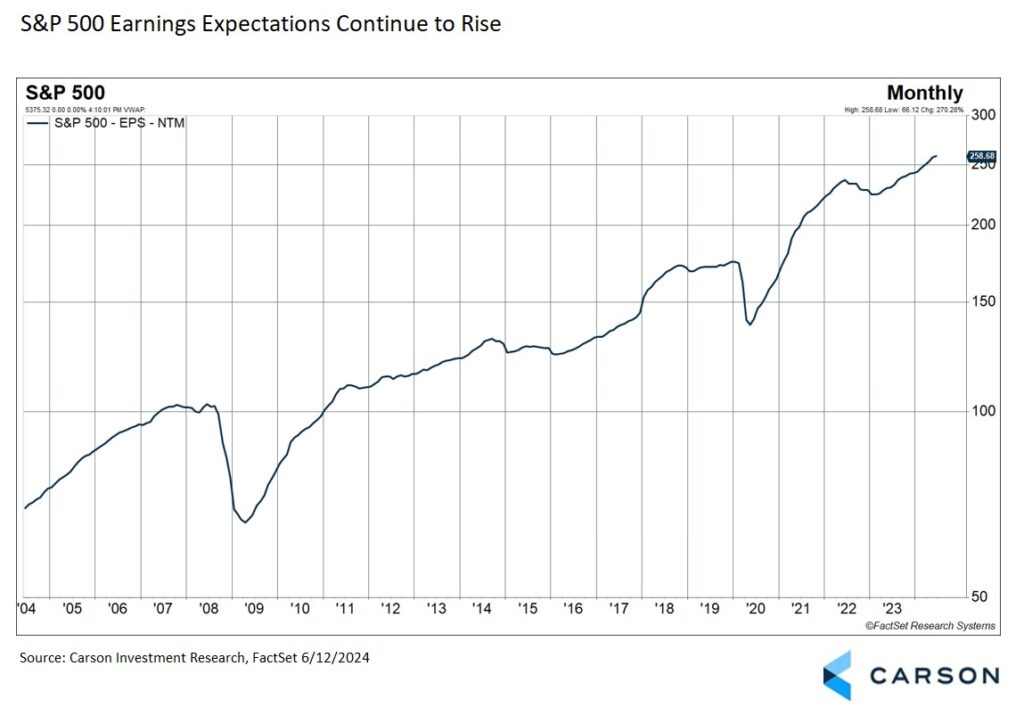

A better baseline perspective to take: Stocks are a long-term investment that can continue to provide returns above more conservative assets as long as companies can continue to grow earnings. And, historically, companies can grow earnings as long as the global economy grows, which is something it has been doing much more often than not. As Sonu Varghese wrote late last year, that likely makes stocks the best investment over the next five years.

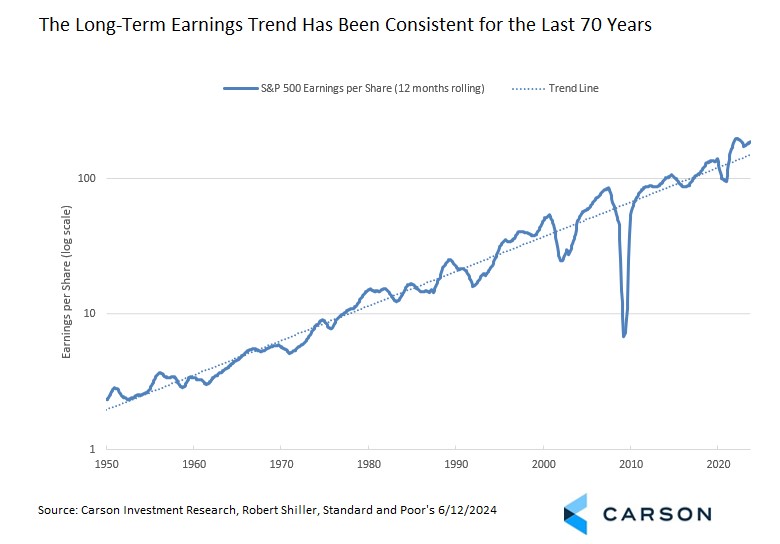

On a much more reasonable scale than millennia, as seen below S&P 500 Index companies have been able to grow earnings along a fairly steady trend over the last 70 years. There have been short-term fluctuations based on the economic environment, but the overall trend has been strong. Next time you’re wondering why own stocks over the long run, ask yourself if you think companies can grow earnings over the long run. If you’re not sure of that, ask yourself if you think the U.S. economy can grow over the long run, then work your way backwards.

Stock gains are fundamentally about earnings growth. There is a more cyclical element related to valuations, but over time that tends to average out to near flat. Valuations generally reflect what investors are willing to pay for future earnings. They can get high when investors are overly enthusiastic and low when investors are pessimistic.

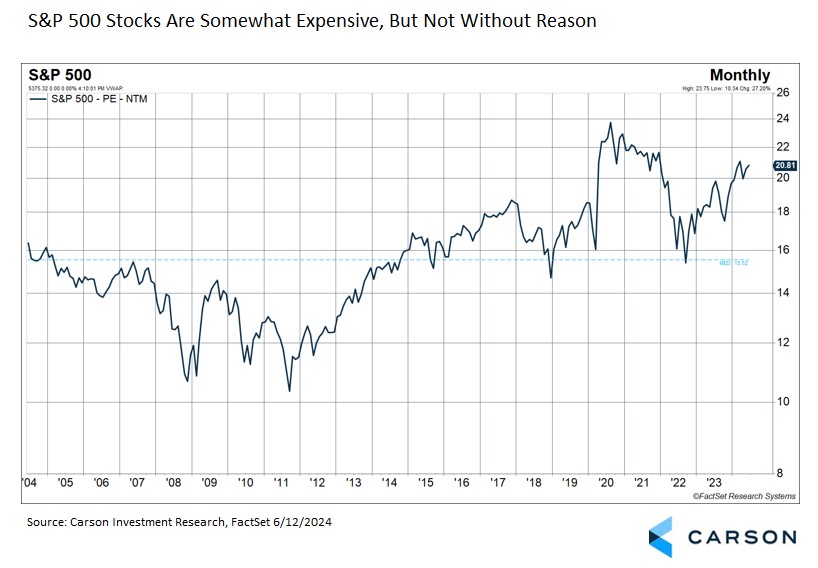

The most well-known valuation measure is the price-to-earnings ratio (P/E), which captures the amount investors are willing to pay for a dollar of last year’s or next year’s earnings as a kind of proxy for long-term earnings. The higher the P/E, the more expensive valuations are. In between, there is some level that markets will tend to return to over time, which can have some impact on the longer-term outlook.

But there are a couple of tricky things above valuations. First, they have very little value as a market timing mechanism (say, the next 1-3 years or sometimes longer). Stocks can stay over- or undervalued for extended periods. Second, the neutral level of valuations depends on a lot of factors, some of which are changing all the time. Some factors, like higher expected inflation and high interest rates, generally weigh on valuations, although inflation and rate uncertainty can help justify higher stock valuations if it makes bonds (as an alternative to stocks) more volatile.

Right now, S&P 500 valuations are somewhat expensive relative to history (about 20.8 versus a 20-year median of 15.5) but not without reason.

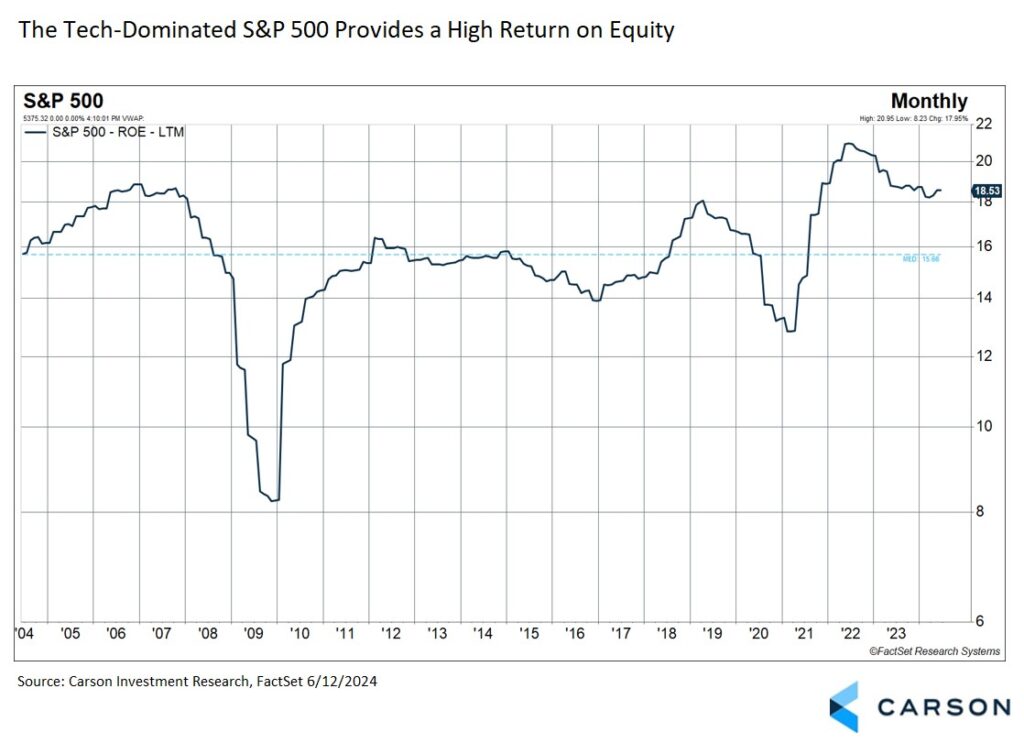

The S&P 500 is now dominated by technology-oriented companies that are able to run very efficient businesses. That has boosted the overall profitability of the broad index. One way to measure this is return on equity, profits as a percent of owners’ equity (aka shareholders, although as an accounting measure). While not as far above its historical median as valuations, it does help show why valuations are justifiably elevated, even if it doesn’t account for all of it. (And note that ROE is backwards looking.)

Big picture, we don’t think there’s a reason right now for investors to shy away from US stocks in the long run. In our own portfolios we have mitigated some valuation risk by adding to lower valuation small and mid-caps. When we mention this, we do often hear concerns about the weak price momentum they’ve exhibited relative to the S&P 500. But that’s how markets work. Segments of the market showing strong momentum are usually expensive; weak momentum segments of the market are usually cheap. Our goal is to find the best mix of opportunities. The S&P 400 Index of mid-cap stocks currently has a P/E of 15.1, close to its long-term median. For the S&P 600 Index of small cap stocks, it’s 14.0, below its long-term median.

Stay on Top of Market Trends

The Carson Investment Research newsletter offers up-to-date market news, analysis and insights. Subscribe today!

"*" indicates required fields

The key takeaway is that the long-term trend for earnings growth is still solidly in place and 12-month forward near-term earnings expectations continue to rise. With little sign of a recession on the near-term horizon, we continue to overweight equities and have high conviction in earnings in the long run.

For more content by Barry Gilbert, VP, Asset Allocation Strategist click here.

02279071-0624-A