We’ve gotten a lot of questions on China, including what’s happening there and how it’ll impact the US, and potentially, financial markets. We’re going to tackle all of those in this blog.

1. What’s happening in China?

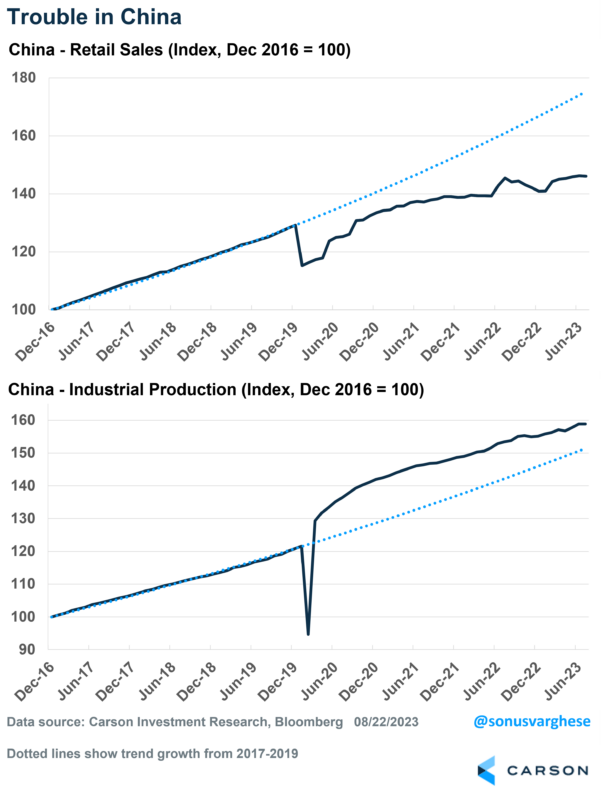

The economy is in trouble. Retail sales are up just 2.5% year over year, well off the pre-pandemic average pace of 7-10%. Usually, the industrial side of the economy makes up for slow consumer spending, but not this time. Industrial production is up just 3.7% since last year, which is well below the average 6% pace we saw before the pandemic.

Over the last few years, exports have been a big driver of growth, but exports have fallen almost 15% over the past year as the rest of the world shifts spending from goods, China’s main source of exports, to services in the current post-pandemic environment. Perhaps even more concerning was that imports also fell 12% over the past year, which is a sign that internal demand in China is really slowing down.

2. What does that mean for their economy?

Economic growth in the second largest economy in the world is set to slow meaningfully. In inflation-adjusted terms, the Chinese economy grew an average of 7.7% per year between 2010 and 2019. That’s slowed to 4.4% over the last 3 years (2020-2021), and it looks like growth is likely to slow even further, perhaps to 3-4%.

3. Why is the economy slowing anyway?

In the US, just under 70% of the economy is made up of consumer spending. However, in China, that’s under 40%. It’s the supply-side that matters more, and that’s driven by investment spending, which accounts for 44% of GDP (versus about 20% in the US).

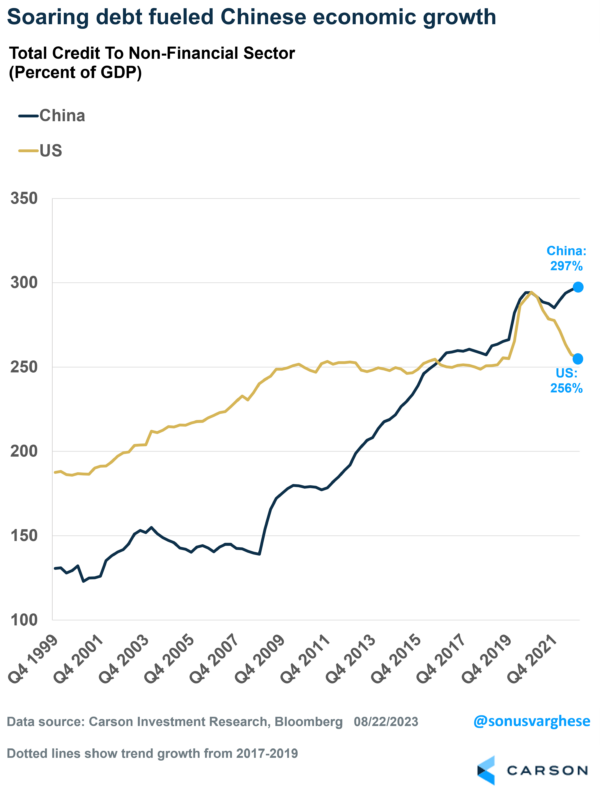

The problem is that a lot of this investment spending was in the real estate sector, and that was on the back of rising debt. Overall debt to the non-financial sector soared over the past decade, from about 140% of GDP at the end of 2008 to almost 300% at the end of 2022. Contrast that to the US, where it’s stayed relatively steady around 250% of GDP. This was how China grew after the Great Financial Crisis. A lot of the debt went to goose up real estate activity, which by some estimates accounts for just under 30% of GDP (versus about 17% in the US).

However, authorities were aware that it drove a lot of unproductive “investments,” including infrastructure, like airports, bridges, and highways. Overbuilding is present on the residential side as well. The that about one-fifth of apartments in urban China (about 130 million units) were estimated to be unoccupied in 2018 (when the latest data was available).

Authorities started clamping down a couple of years ago. You may have heard of problems with Evergrande, China’s second largest developer. They experienced massive losses amid new regulations, ended up defaulting on debt payments, and eventually filed for bankruptcy. And they were just one among many.

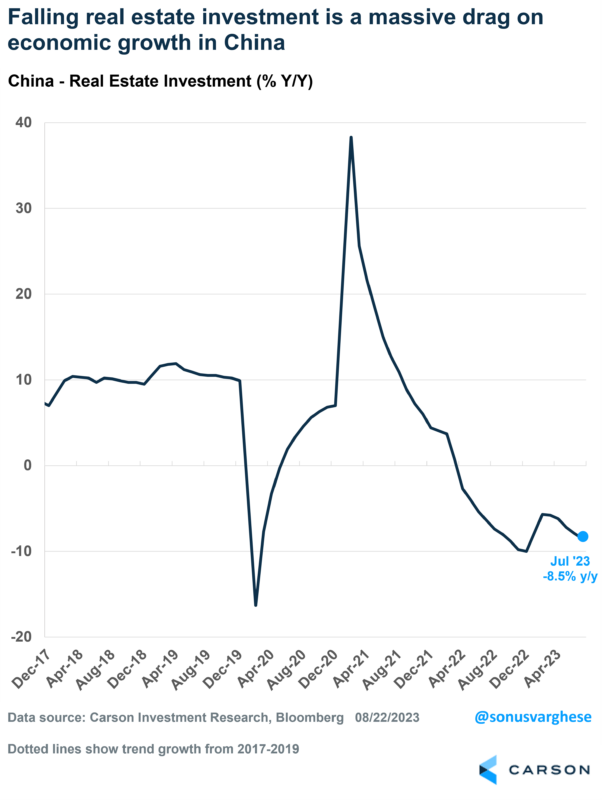

Investment in the real estate sector was running around 10% annually before the pandemic. As of July, real estate investment is down almost 8% year over year (y/y). So, it shouldn’t be a surprise that real estate activity has crashed.

- Property sales are down 15% y/y in volume terms

- Floor space under construction is down 7% y/y

- New home starts growth is down 26% y/y

This is not good news for Chinese households. The absence of safety net programs (like social security and Medicare) mean Chinese households save a lot, and they typically invest income and savings in real estate/homes. Crashing prices means they’re less likely to spend their savings on real estate. But that also means there’s less money going into the sector.

Developers in China have historically raised capital by selling apartments they’ve yet to build and used that capital to finance operations. This was an easy game to play when prices were rising and demand was high. Now, it’s gone the other way, and there’s no easy way out. Developers are scrapped for capital, leading to even more defaults. Another large developer, Country Garden, is in the news now for this very reason (they recently missed a couple of interest payments).

4. Can’t they just bail out the real estate sector?

They probably could, but they’re reluctant to do so. Authorities have been clear that the country cannot depend on real estate for economic growth. They seem to recognize that putting more money behind bad investments is not the way to go. As the economists now estimate that China now has to invest $9 to produce each dollar of GDP growth, up from $5 dollar a decade ago. There’s going to be a period of hard adjustments ahead.

5. Can China boost households by sending checks, like the US?

Historically, any “stimulus” has been on the supply-side, typically by making it easy to borrow. However, they seem wary to do so now, for a lot of the reasons I mentioned above, they’re only nibbling around the edges with a few interest rate cuts.

But Chinese authorities appear to believe that empowering households to consume more would undermine state authority, and as such, they are.

More importantly, transforming the economy from one led by investment to one led by consumption would involve a lot of income redistribution, for example by shoring up China’s weak social safety net by introducing something akin to social security and better unemployment benefits. But that would mean less money would be going to the local governments and the industrial/property. Those kinds of changes just aren’t politically palatable, and hence the economic adjustment is going to be hard.

6. Will this impact the US economy?

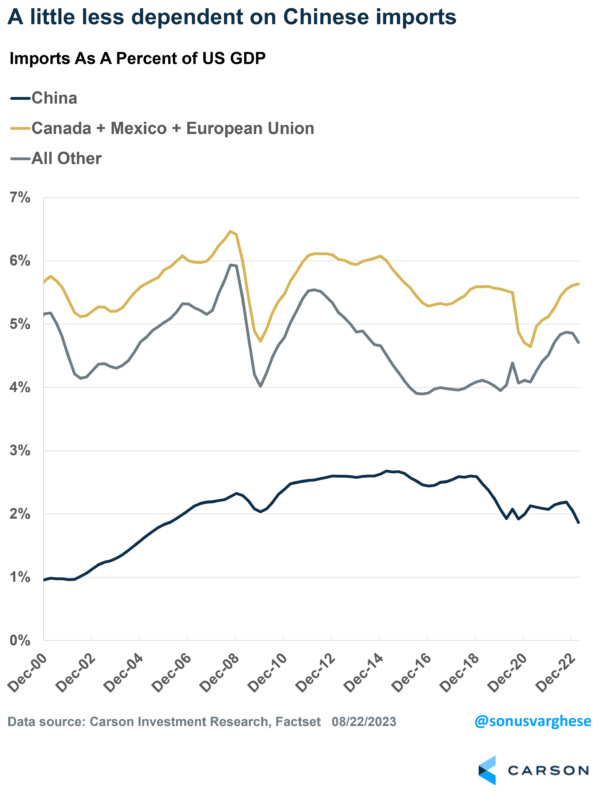

From an economic perspective, not much. The reality is that US imports from China have been falling a lot over the past year – we need less of pandemic related materials and other goods as people continue to spend more on services now. There is some decoupling going on as well, with goods imports from China falling as a percent of GDP. It’s fallen to below 2% of GDP right now – the lowest since 2006. Instead, imports from everywhere else have picked up.

Trade with China is not going to zero but it’s likely to get relatively smaller. Note that part of what’s happening is increased trade with Asian nations like Vietnam, Philippines, and India, as imported goods get re-routed from China to the US via these countries.

The reality is that China needs the US more than the other way around. The US economy is reliant on consumption, and that’s internally generated demand. Whereas China is very dependent on investment and exports, and for that they need demand outside to be strong.

7. Can they “hurt” the US by selling treasuries?

If the Chinese sell treasuries, we see it as more of a sign of their weakness than anything else.

Historically, they’ve been able to hold their currency relatively lower to help the export sector. How did they do that? The Chinese central bank sold their currency (CNY) and bought USD assets, namely treasuries. Though over the last decade they’ve purchased more agency-mortgage backed securities (MBS). They weren’t buying US treasuries as a favor to the US, but rather, because they had to. They were reliant on exporting to Americans and got dollars in return. With those dollars, they bought US treasuries/securities, and kept their currency relatively low.

Stay on Top of Market Trends

The Carson Investment Research newsletter offers up-to-date market news, analysis and insights. Subscribe today!

"*" indicates required fields

The problem now is that capital is trying to leave China because of slowing growth. That puts downward pressure on their currency – more than they would like. So, they’re starting to sell off some of their “war chest” of reserves (Treasuries and US agency mortgage-backed securities) to defend the currency. That’s essentially the equivalent of selling US dollars and buying yuan.

So, as I said, it’s a sign of economic weakness more than anything else.

8. Will this impact financial markets?

If there’s any impact, it’ll be in financial markets via headline risk, similar to 2015-2016 when China devalued their currency. The difference is that the US economy is now on firmer footing.

- If the Chinese are selling down their reserves of MBS and Treasuries, that could put more upward pressure on US Treasury yields, though only at the margin since we’re talking about the most liquid market in the world.

Most of what happens with yields is still going to be driven by US growth prospects and Fed policy expectations. US economic growth, in sharp contrast to China, has been resilient – rising 2.6% over the past year, which is faster than pre-pandemic. And it may be accelerating in the 3rd quarter, based on a slew of solid economic data we received recently.

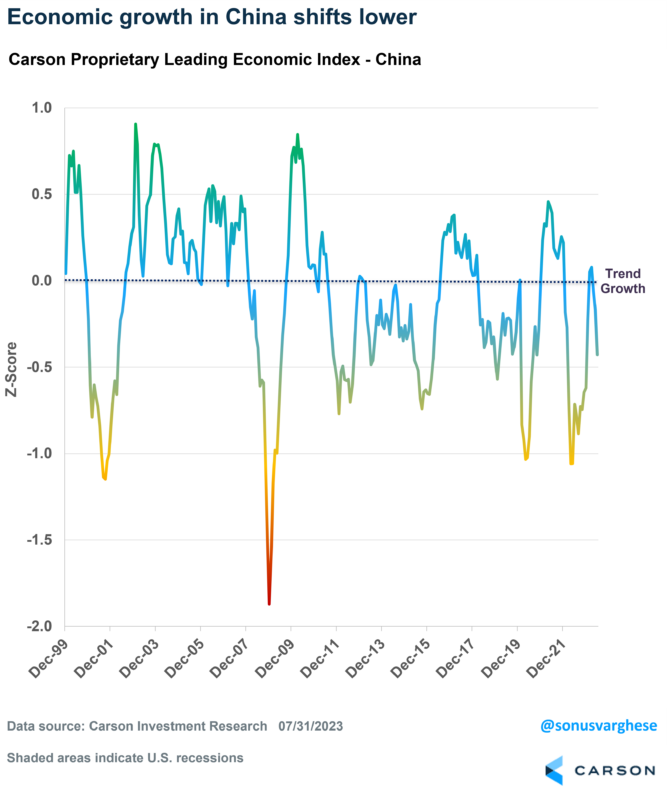

China’s problems didn’t start this year. I’d argue it started a decade ago as growth became increasingly reliant on debt. Our leading economic index for China has shown economic growth downshifting below trend for several years now, with only brief periods when activity picked up.

It’s quite amazing to think that the US economy is probably growing faster than the Chinese economy at this point. That’s something we haven’t seen in decades, and right now, the US economy’s relative strength looks set to continue. That’s a big reason why we continue to be overweight US equities and underweight emerging markets, where China as the largest constituent.