Happy Tax Day! Or not. Though if you’re a large multinational, tax day in the US doesn’t really matter. In fact, to “celebrate” Tax Day, I’m going to discuss how the US tax code impacts the trade deficit. This is very relevant now because of everything going on around tariffs, with one of the stated goals being to reduce the trade deficit. In fact, the Liberation Day “reciprocal tariffs” had nothing to do with tariffs imposed by other countries on American goods and everything to do with the US trade deficit in goods with each country (I wrote about this at the time).

Take Ireland for example. In 2024, Ireland exported $103 billion of goods to the US and imported just $16 billion of goods from the US. That resulted in an $87 billion trade deficit for the US with Ireland. That’s about 7% of the US trade deficit in goods with the entire world (total $1.2 trillion in 2024) and a whopping 37% of its trade deficit with the European Union ($236 billion in 2024).

Keep in mind that Ireland is a tiny country whose GDP is under $600 billion, which is just about 0.5% of total world GDP. The population is about 7 million. I’m sure the Irish have a darn good work ethic and are extremely productive relative to the rest of the world, but their US exports clocking in at 17% of GDP should immediately make you suspicious. Turns out there is more than meets the eye.

Ireland: A Pharma Haven Created in DC

Most of America’s trade deficit with Ireland is actually just pharmaceuticals, and overall, pharmaceuticals accounts for about half of America’s trade deficit with the EU. As Brad Setser, a trade expert at the Council on Foreign Relations, points out, Ireland’s success is a direct result of incentives in the 2017 Tax Cut and Jobs Act (TCJA). It was signed into law by President Trump in his first term and ironically, the goal was to reshore US production, and profits. That didn’t turn out to be the case. Instead, it accelerated pharma imports into the US and widened the trade deficit in pharmaceuticals significantly. Some numbers:

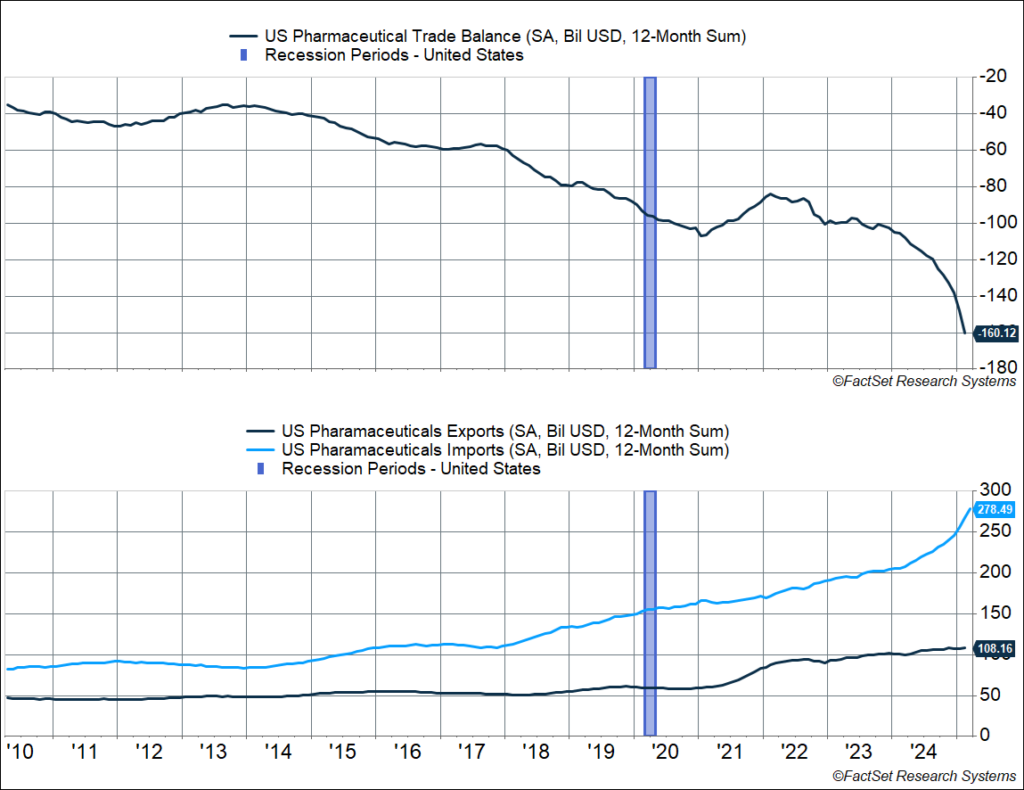

- In 2017, the US imported $110 billion of pharmaceuticals from the rest of the world. That’s risen by 153% to $278 billion over the 12 months through February 2025.

- In 2017, the US exported $51 billion of pharmaceuticals to everyone else. That’s risen 112% to $108 billion as of February 2025. Not bad, but not as much as imports have surged.

- As result, the pharmaceutical trade deficit has surged from $59 billion in 2017 (7% of the overall goods trade deficit) to $160 billion in February 2025 (12% of the overall goods trade deficit).

The chart below starkly illustrates what’s happened since 2018 (post-TCJA). Pharmaceuticals are now the second largest manufactured import into the US (after automobiles) and a key driver of the trade deficit. And this one is actually made in DC. If I were to place odds on the likelihood of new tariffs bringing manufacturing back to the US, the unintended consequences of the TCJA would certainly incline me to lower them some.

Ireland has been a well-known tax haven for over a decade now, with US tech companies, cola firms, and pharma companies rerouting profits through the country to avoid US taxation, so much so that Ireland’s GDP is completely skewed by multinationals shifting profits and intangible assets (intellectual property, including cola formulas) to Ireland. It’s even skewing EU GDP growth, but it has nothing to do with domestic demand in Ireland. For example, in 2023, Irish GDP fell by 5.5%, but that’s because multinational activity contracted by 16.2%. Their statistics office releases another measure called “modified domestic demand,” and that grew 2.6%.

But since 2018, we’ve seen a shift with pharmaceutical imports surging. Here’s a brief look at what happened, courtesy of Brad Setser at the Council of Foreign Relations. TCJA made big changes to the corporate tax code, lowering the corporate tax rate from 35% to 21%. But it really created 3 tax rates:

- A new 21% corporate tax rate

- A reduced 13.125% rate on the export of intangibles – as a result of which tech companies like Google and NVIDIA on-shored their intellectual property

- A 10.5% global minimum on intangible income (“GILTI”)

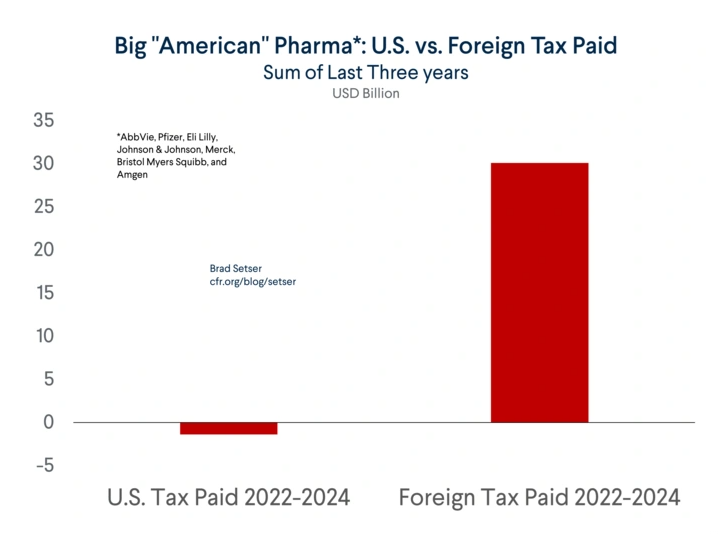

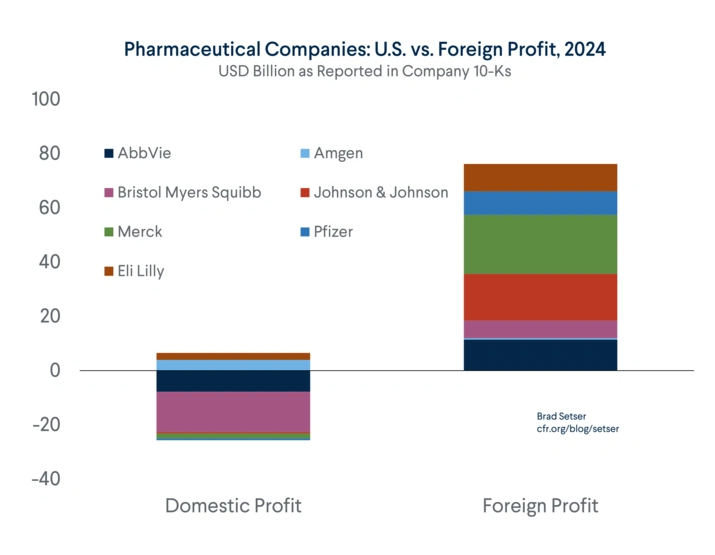

The last one is important for pharma companies as their profits are mostly driven by intangibles like patents and marketing. The cost to produce isn’t that high. Since 10.5% is lower than the new corporate tax rate of 21%, pharma companies shifted production outside the US, making significant investments in tax havens like Ireland, and even places like Singapore. Thanks to a combination of offshore production, offshore taxation (often negligible), and the 10.5% GILTI rate, Large US pharma companies pay a lot less in taxes — with big US pharmaceuticals not paying any tax in the US at all.

What’s remarkable is that the big US pharma companies reported losses on US operations, with the entirety of their profits generated abroad. Ironic, because drug pricing is pretty steep in the US and so you’d think the US would be a profit center. But TCJA incentivized moving production offshore.

To summarize, here’s where we ended up post-TCJA

- Lower tax revenue

- A shift of production (and jobs) offshore

- A higher trade deficit

No wonder Brad Setser called TCJA the Pharma Tax Cuts and Irish Jobs Act.

But this may be ending and not in a great way. Ideally, the US would be fixing the TCJA, and there’s a good opportunity to do it because Congress is in the middle of figuring out a new tax bill. Instead, the “fix” is coming via tariffs, which is basically compounding the bureaucracy now. The Trump administration is looking to use national security grounds to investigate imports of pharmaceuticals (and semiconductors), in a bid to impose 20-25% tariffs — these goods are currently exempt from the 10% baseline tariffs that the US started collecting on April 5th (rates over this were suspended for 90 days for most countries).

All this is also why negotiations are going to be extremely difficult. As part of the “reciprocal” tariffs, the US imposed 20% tariffs on EU goods. Ireland kind of got away with one here because if they were not part of the EU, their reciprocal tariff rate would have been about 40% using the calculation the administration used for everyone else. Still, if the administration’s goal to reduce America’s trade deficit with the EU, they’re going to have to discuss how the US tax code is a big part of the problem here. The Trump administration will argue that “non-tariff barriers” have to go away, but in Ireland’s case, their non-tariff barrier is that their corporate tax rate is really low. It’s highly unlikely they increase taxes in Ireland as part of any deal. You can see how all this gets complicated very fast.

At the end of the day, the bottom line is if the goal is to reduce the trade deficit, you’re going to have to tackle the pharma trade deficit. Either you put heavy tariffs on pharmaceuticals and/or get countries like Ireland to increase their tax rates. That’s how you disincentivize offshoring of production and try to get it back to the US. However, you can see how this means one or both of two things:

- Prices will go up (including for generics, which are mostly coming from India and China)

- Reduced profit margins for pharmaceutical companies (they do have high margins)

It gets to the point that a trade war doesn’t simply involve realigning trade flows across the world, and in and out of the US. It’s also going to change how companies make profits around the world, and this is important because 40% of S&P 500 company revenues come from outside the US. If you break how the global trading system works right now, you’re going to break how capital (and profits) flows around the world as well. Over the last 20 years, US multinationals (and thereby the US stock market) have been big beneficiaries of the existing trade regime. That may be ending. This is not to say they’ll stop making profits (even if it means higher prices for consumers), just that there’re likely to be a transition and right now there’s a lot of uncertainty as to how exactly the transition is going to happen, and how painful it may or may not be.

Stay on Top of Market Trends

The Carson Investment Research newsletter offers up-to-date market news, analysis and insights. Subscribe today!

"*" indicates required fields

For more content by Sonu Varghese, VP, Global Macro Strategist click here.

7863171.1-0425-A