I’ve noted in the past how the US economy primarily relies on consumer spending, and since consumer spending is driven by income growth, the employment situation is pretty much the ballgame. And right now, things are getting a tad uncomfortable. We’re not quite worried yet, but simply recognize that risks are rising.

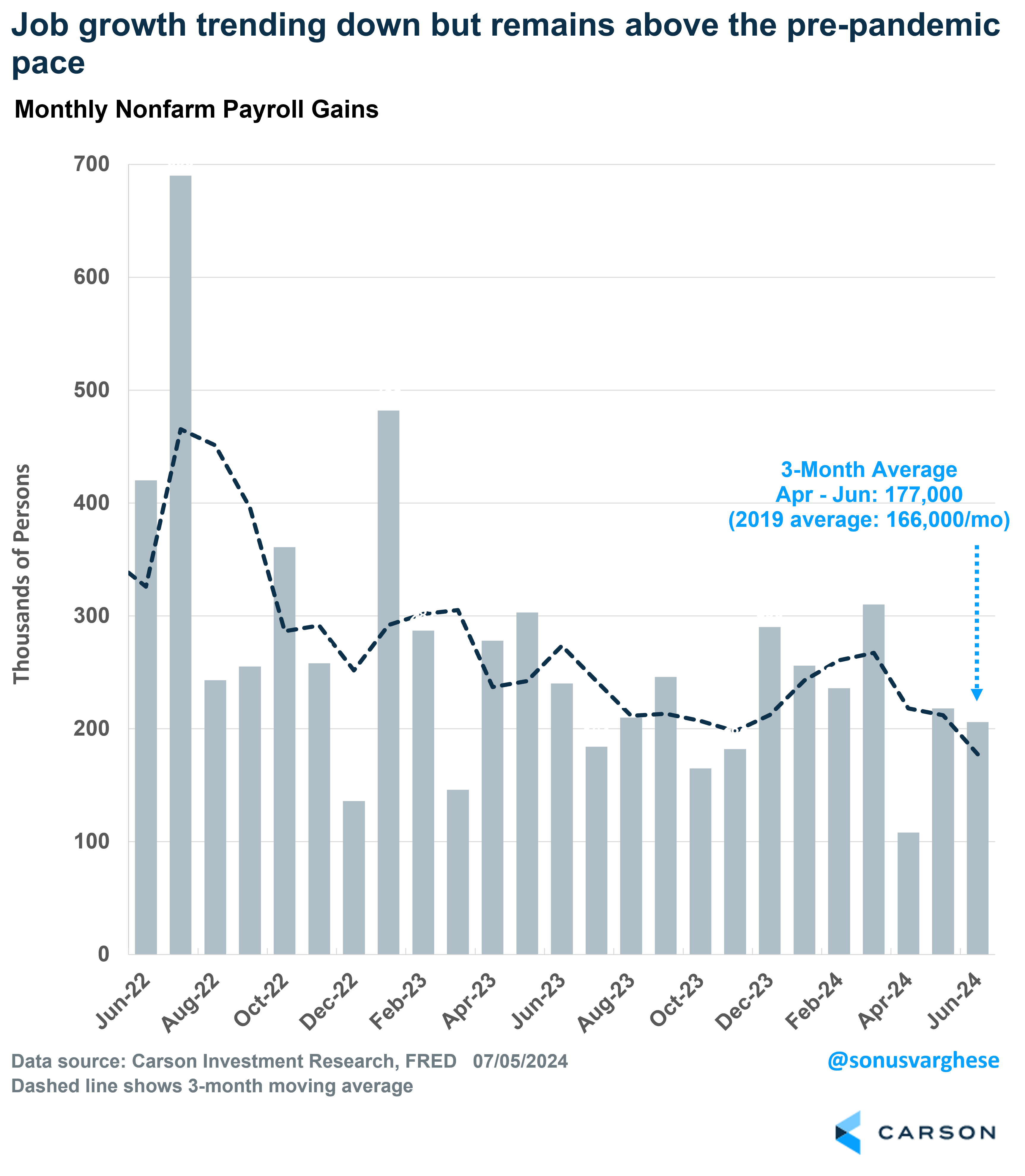

What’s running strong, month after month, is payroll growth. The economy created 206,000 jobs last month, above expectations for a 190,000 increase. These numbers can and will be revised, and so it helps to look at the 3-month average. That number has been trending down since earlier this year, but it’s at a healthy 177,000 right now, above the 166,000 average pace in 2019.

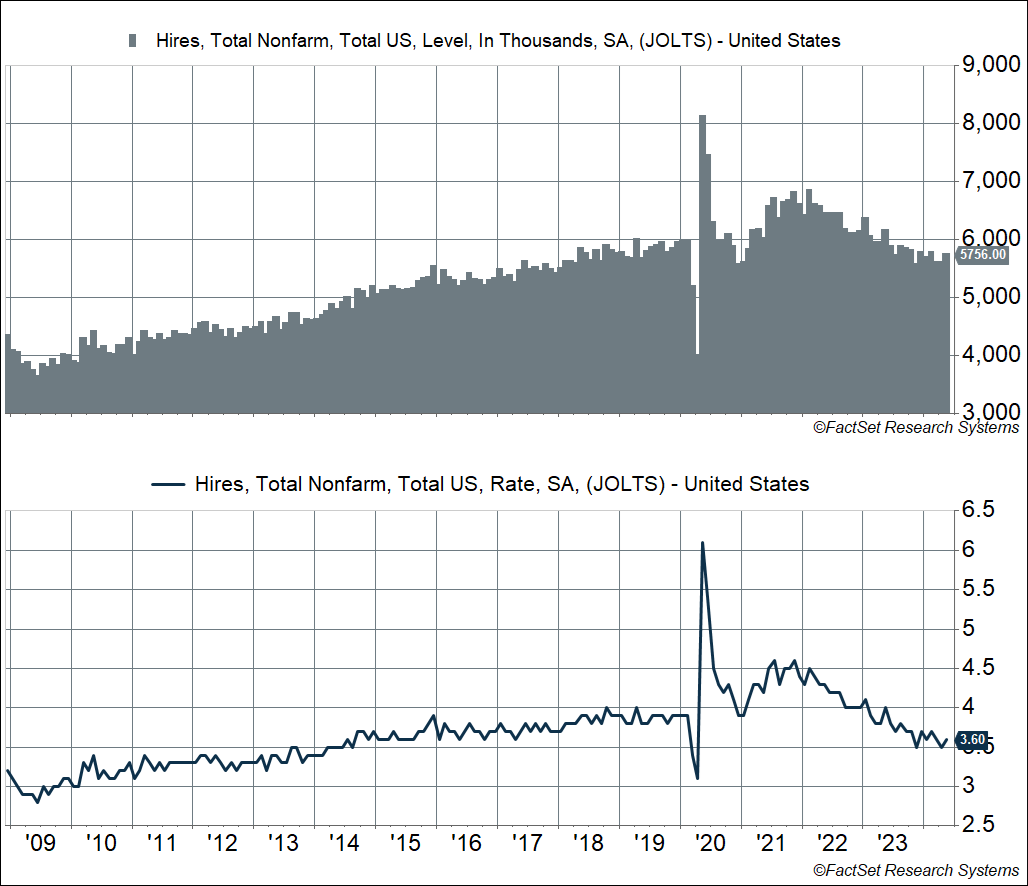

The payroll growth numbers I quoted above are “net employment numbers,” i.e. overall hiring net of separations, whether voluntary (people quitting jobs) or involuntary (layoffs). Breaking it down, overall hiring has eased. It’s now running around 5.8 million, which matches the 2019 average. However, the labor force is much larger, and hiring as a percent of overall employment is currently at 3.6%. That’s below the 2019 average of 3.9% and matches what we saw all the way back in 2014. Not exactly weak (the hiring rate collapsed below 3% during the 2008-2009 recession), but not too hot either. In other words, it isn’t easy to find a job if you’re looking for one right now, a very different situation from what we saw in 2021/2022 through early 2023.

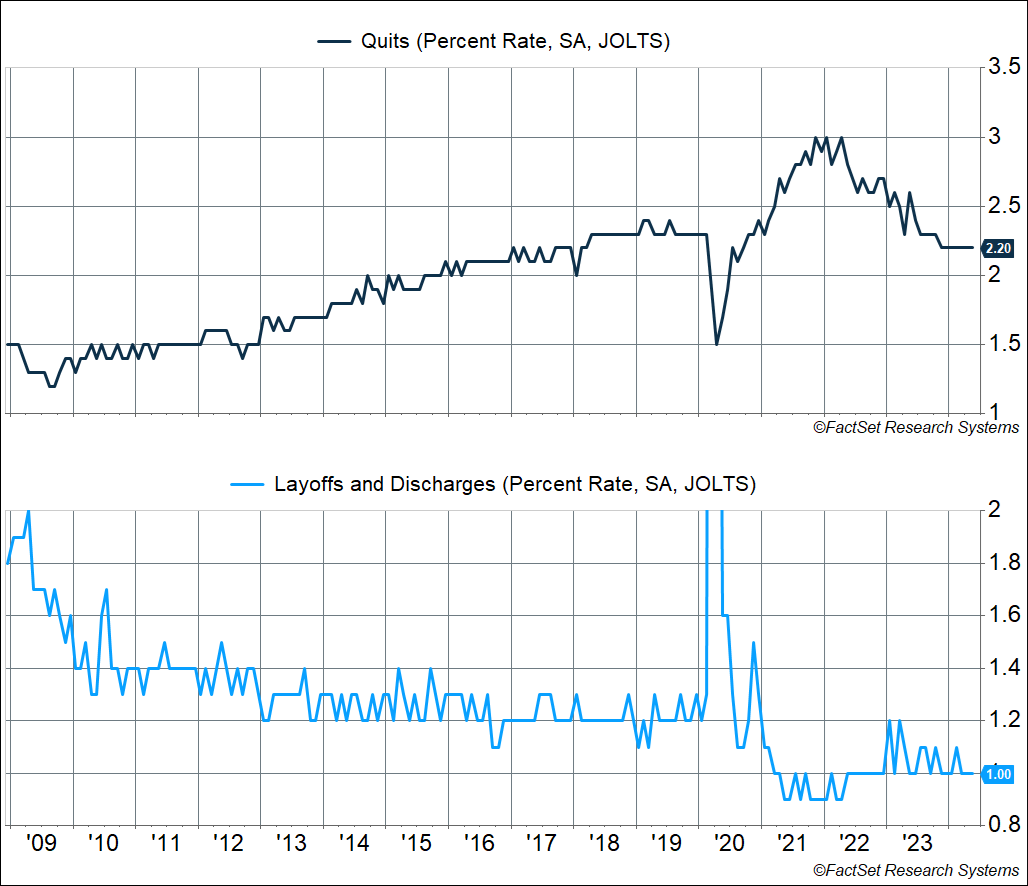

At the same time, “net employment” is high because separations are low. People are quitting their jobs at a much slower pace than before – the “quit rate” has been unchanged at 2.2% for 7 months now. That’s only a tick lower than what we saw in 2019 and is indicative of a healthy employment situation. If the labor market were weak, the quit rate would be much lower. Even better, layoffs are running historically low. As a percent of the employed workforce, the “layoff rate” is at 1%. It averaged 1.2% in 2019, which was considered really low.

What’s likely happening is that companies did a lot of hiring in 2021/2022 (maybe too much) and are now easing up. If companies were truly pessimistic about sales and profits, they would be letting more people go. One positive aspect of this is that workers who stay in their jobs longer get more productive.

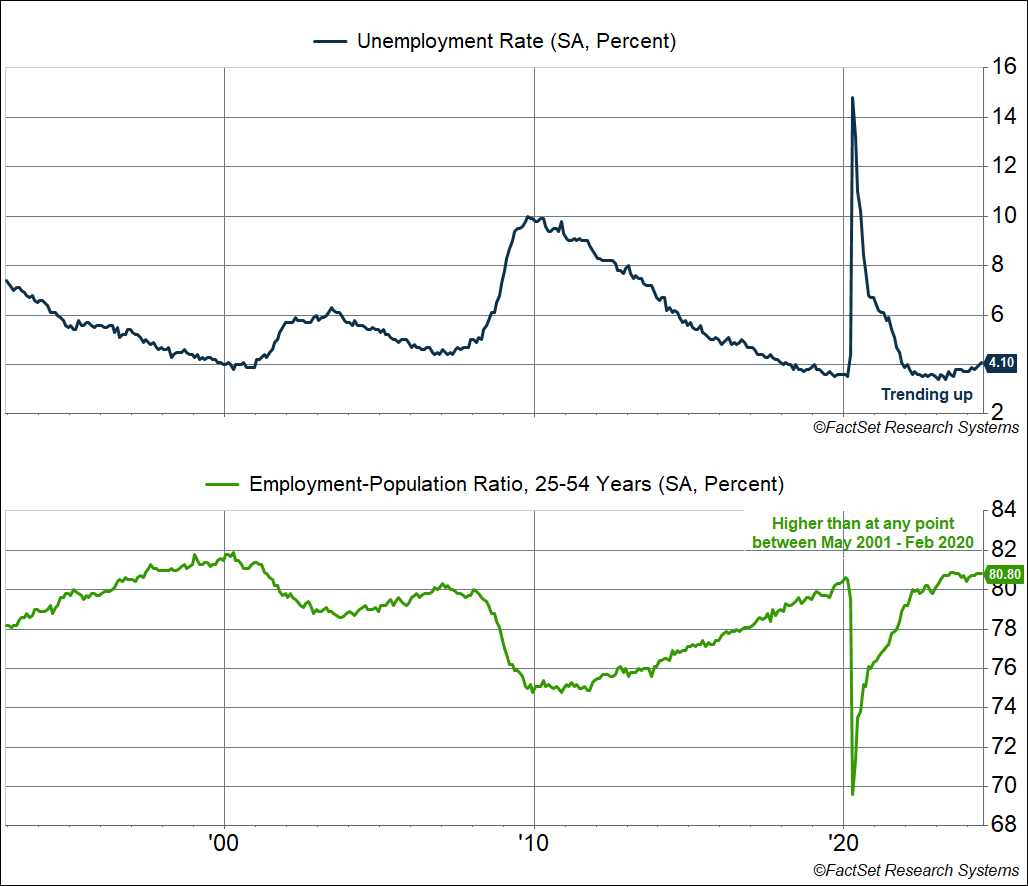

The other side of all this is that we’re seeing the unemployment rate inch higher and that’s the most visible sign that employment is cooling. It rose to 4.1% in June, up from 3.7% a year ago. That’s still relatively low, but the recent uptrend is not encouraging. Now, part of this is because people who don’t have jobs are looking for work more actively than they did before.

Stay on Top of Market Trends

The Carson Investment Research newsletter offers up-to-date market news, analysis and insights. Subscribe today!

"*" indicates required fields

I’ve mentioned in previous blogs how I prefer looking at the “prime-age” (25-54 years) employment-population ratio, since it gets around definitional issues that crop up with the unemployment rate (someone is counted as being “unemployed” only if they’re “actively looking for a job”) or demographics (an aging population with more people retiring and leaving the labor force every day). The prime-age employment population ratio was unchanged at 80.8% in May. That’s only slightly below the high from last summer, and above anything we saw between 2001 and 2019 (when it peaked at 80.4%). This by itself should tell you the labor market is strong, with more people participating in it.

The Fed Needs to Act

The upshot of all the above data I cited is that the labor market remains healthy, but risks are rising. Once the labor market really starts to weaken, you can get a snowball effect, and it’s hard to tell when it stops. That is why there’s really no such thing as a mild recession – the three recessions prior to the pandemic recession (1991, 2001, 2008-2009) were all bad from an employment perspective, as it took years for the labor market to recover. Once the labor market starts to weaken, the economy gets into a negative feedback loop of low hiring, high layoffs, weak income growth, and falling consumption. At the end of the day, one person’s spending is another person’s income, or company profits. More than anything, it also adversely impacts the productive capacity of the economy in future years.

This is why the Federal Reserve needs to act and pull back on their economic brake pedal, i.e. interest rates. Rates are clearly restricting some cyclical activity right, most notably in the housing sector thanks to 7%+ mortgage rates.

Fed Chair Powell recently admitted that the risks to their double mandate – low and stable inflation and stable employment – are now two-sided. He noted that cutting rates too soon could “undo the good work we’ve done bringing down inflation,” but, cutting rates too late “could unnecessarily undermine the expansion.” This two-sided view of the risks is a big change from a year ago.

Powell and other Fed members continue to maintain that they need to gain more confidence that inflation is headed back to their target of 2%. Yet, recent data have been very encouraging on that front. Inflation is running around 2.5-3% only because of how the government calculates shelter inflation, which really lags real-time, private market data.

At this point, the risks are likely skewed toward the side of the labor market cooling more rapidly than inflation re-heating. The Fed should have enough data to justify starting their rate cut cycle as early as their July meeting in three weeks. However, given their proclivity to waiting, it looks like we’ll have to wait until September. In any case, we’re very likely to see the Fed pull interest rates back this year, so that the expansion can keep going.

For more content by Sonu Varghese, VP, Global Macro Strategist click here.

02310817-0724-A