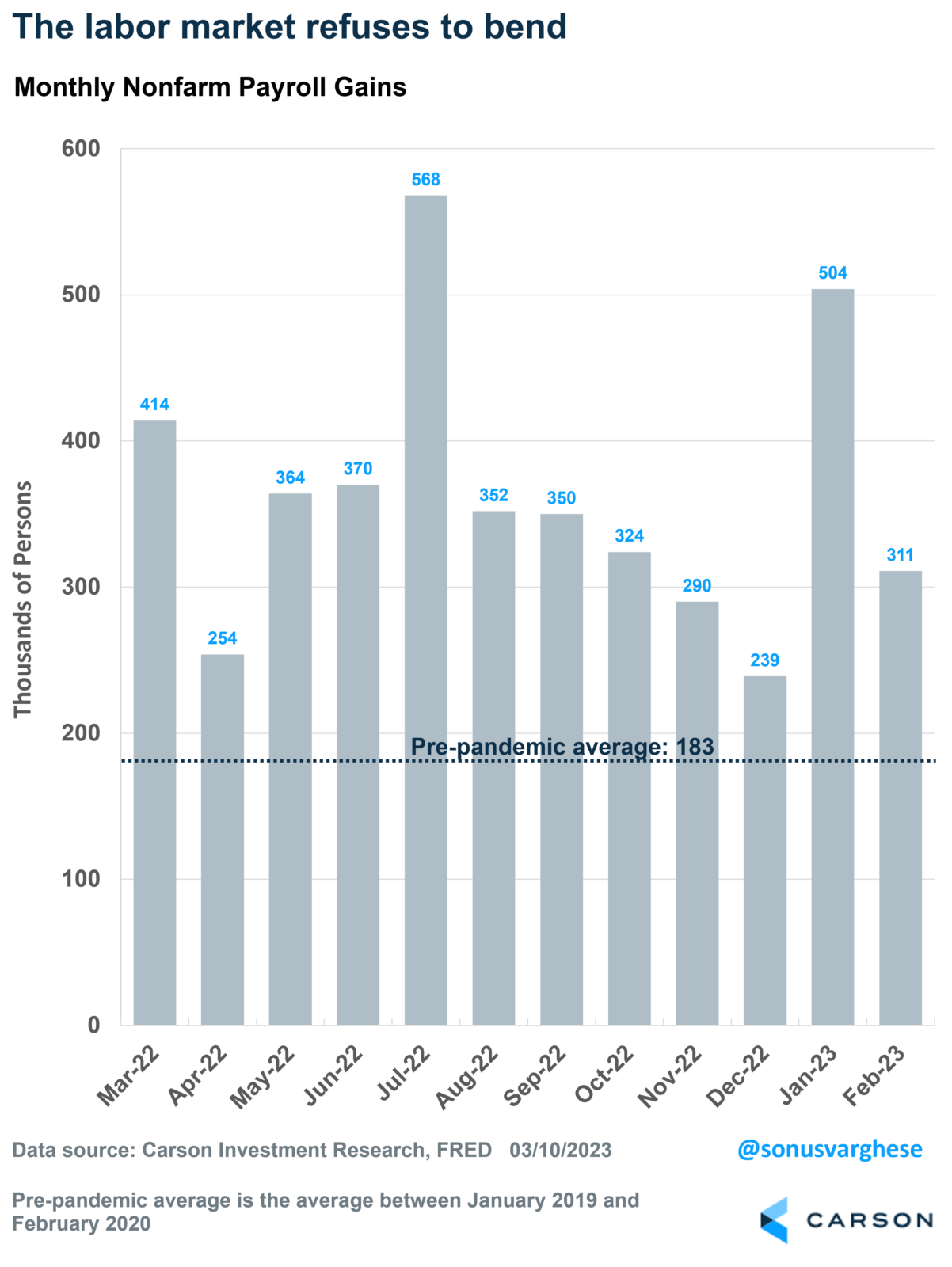

Another month, another solid employment report. Employment rose by 311,000 in February, on the back of 504,000 in January and 239,000 in December. It’s certainly been a warm winter. This is the labor market that refuses to give in, despite the Fed throwing almost 500 bps (5%-points) of rate hikes at it and gearing up for more.

But the unemployment rate rose …

Yes, the unemployment rate rose to 3.6%, up from 3.4% in January. However, that was entirely for positive reasons.

The unemployment rate, as the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) measures it, is the number of people unemployed who are looking for work divided by the size of the labor force. Last month, the number of unemployed people that are looking for work rose by about 240,000. However, that’s because 419,000 people “entered” the labor force, i.e., started looking for work. That’s a sign of a healthy labor market. People will start looking for work only if they think they can get a job.

The labor force measure has issues related to how participation is measured – they count someone as being in the labor force only if someone is looking for work. But a lot of people may not do so for any number of reasons, including not feeling confident in the job market or non-economic reasons like not having access to childcare. The measure also can fall over time because of a lot of retiring baby-boomers.

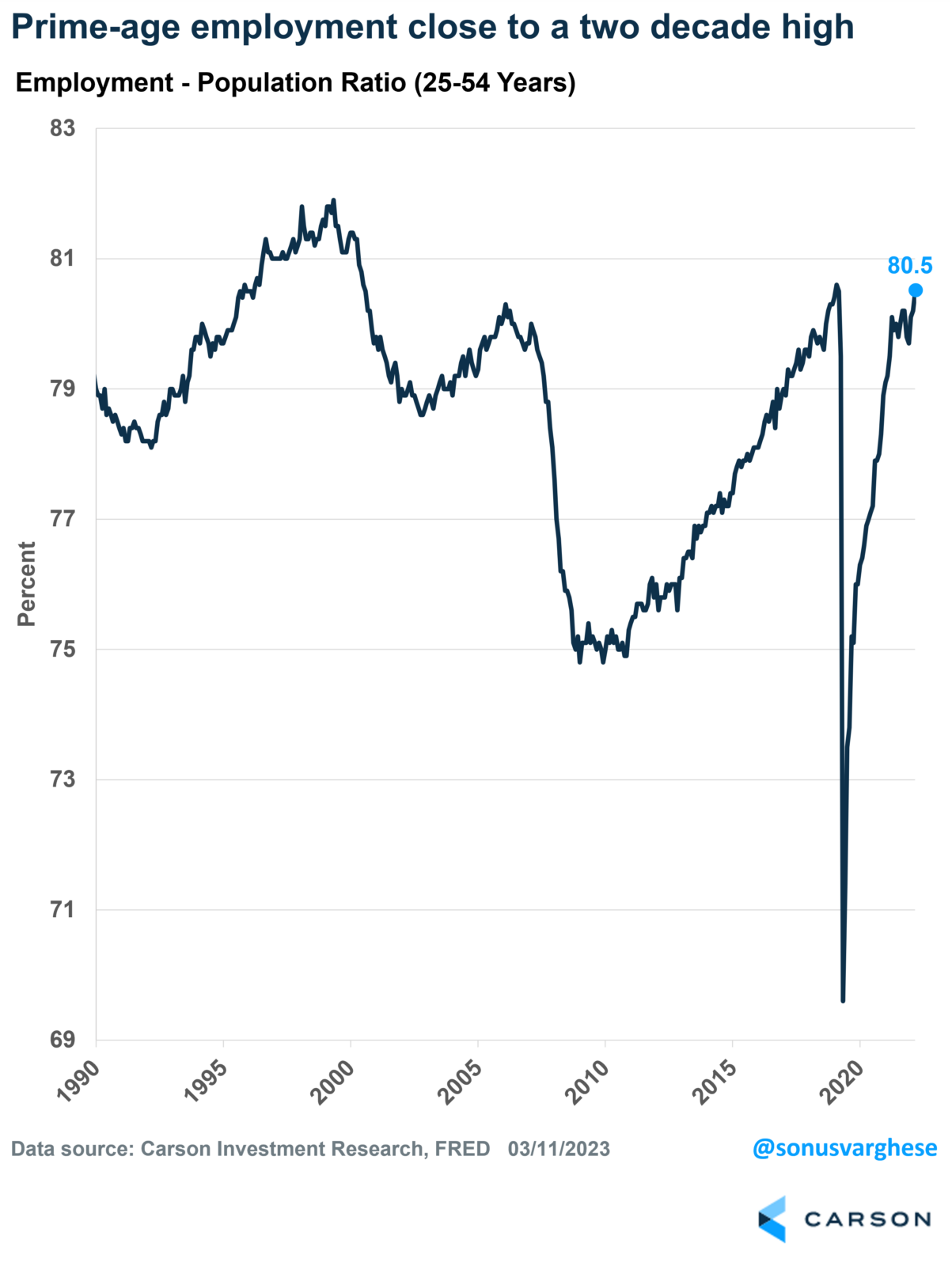

One way to get around these issues is to look at the employment-population ratio for prime age workers, i.e., workers aged 25-54 years. This measures the number of people working as a percent of the civilian population – think of it as the opposite of the unemployment rate, and because we use prime age, you get around the demographic issue as well.

The good news is that the prime-age employment-population ratio just hit 80.5%, which is close to the highest level we’ve seen in a couple of decades.

It helps to recall that we just had a multi-generational black swan event in the form of a pandemic. But once everything re-opened, the expectation was that things would bounce back immediately. And a lot of numbers did, including GDP, employment, and consumption.

However, there were also a lot of people who left the labor force amid the pandemic. And what we’re seeing now is that each month there’s a continuous flow of people back into the labor force, and these people are finding jobs quickly. Just over the past six months, 1.5 million more people have come into the labor force as prospects for finding a job improve.

Make no mistake, this is a really strong labor market in my opinion.

Is the labor market too strong?

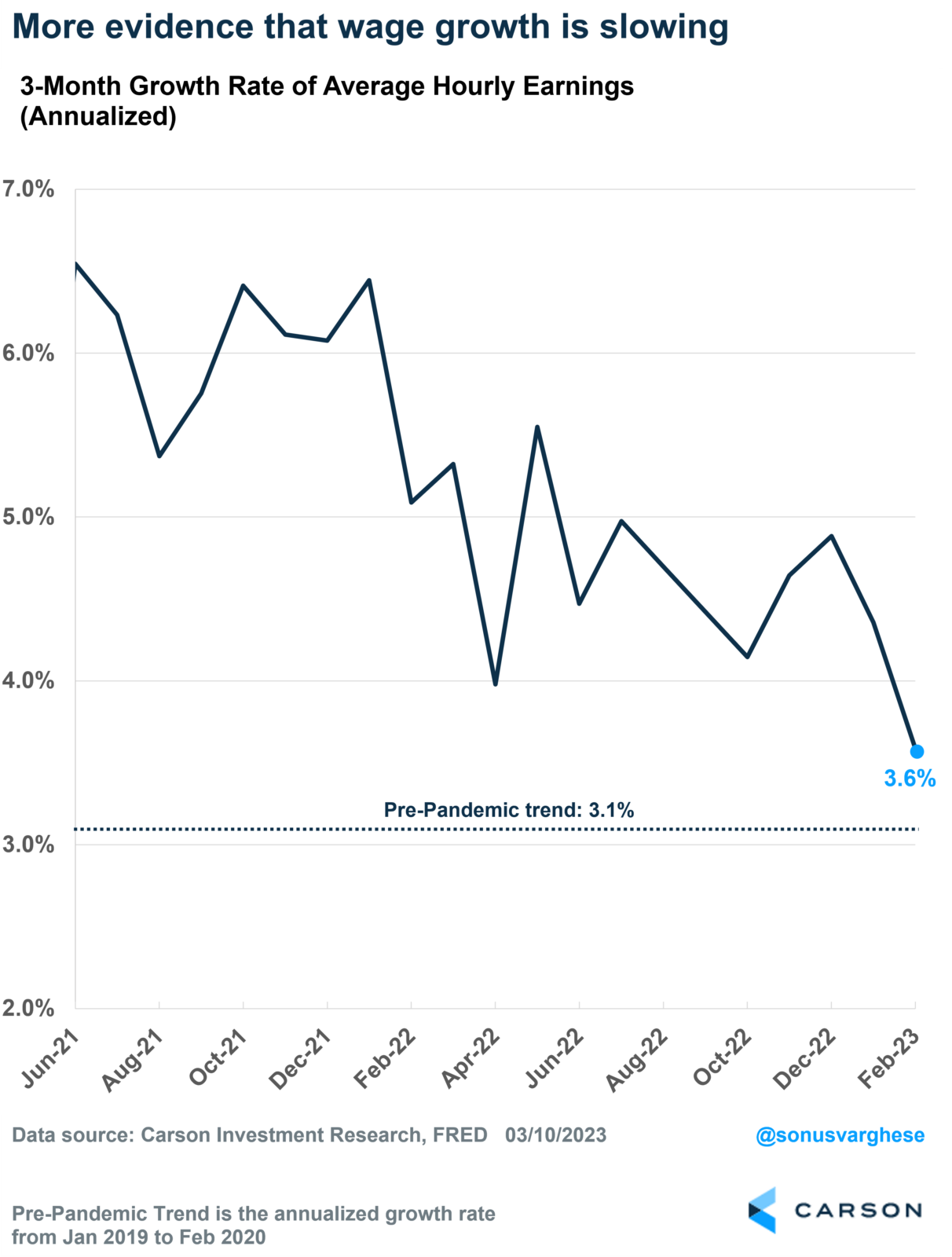

It’s weird to even ask that question, but it matters for the Federal Reserve. In their model for the economy, they see a tight labor market as one that results in stronger wage growth. And strong wage growth can drive demand higher, pushing up prices and inflation.

Well, hopefully, they can rest a little easy on that front. Average hourly earnings rose just 0.2% in February. Over the past three months, wages have been growing at an annualized pace of 3.6%, well below the 6%+ pace we saw last year. It’s getting very close to the pre-pandemic pace of 3.1%.

This backs up other evidence that wage growth is indeed easing, including the Employment Cost Index, which is the gold standard of wage growth measures. The ECI was running at an annualized pace of 4.2% in Q4 2022, down from 4.8% in Q3. The January-February hourly earnings data suggest that wage growth continues to decelerate.

The big question is whether the Fed buys this. Powell’s comments this week in front of Congress did not inspire confidence. It looks like a string of hot economic data has left them questioning their decision to ease the pace of rate increases from 50 bps to 25 bps (as of February) – and wondering if they should move that back up to 50 bps at their March meeting. At this point, markets think the outcome is a coin toss, which is not great as Powell simply injected maximum uncertainty into markets.

But looking beyond the Fed’s March meeting, the big picture is that the labor market appears to remain really strong. This means the economy also remains strong, and that’s not a bad thing as far as markets are concerned. Though it also means the Fed is likely to keep interest rates higher for longer.