Of all the commodities that course through the veins of our world, it seems that none has the power to influence nations, economies, and daily lives quite like oil. It’s the lifeblood of industry, the force that propels most of our cars and planes, and an underlying current of geopolitics. Oil prices have been steadily rising since midsummer and recently jumped higher on news that Saudi Arabia and Russia would continue production cuts through year-end. Supply and demand are in a delicate balance where even a small disruption in production could lead to a shortage of oil and substantially higher prices. Mike Wirth, CEO of Chevron, recently commented, “supply is tightening” and “inventories are drawing” suggesting conditions are ripe for $100 oil prices. This is good news for oil producers but could spell trouble for consumers and the global economy, which is why oil has been an acute focus of economists as of late.

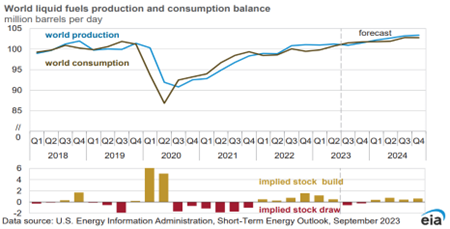

Saudi Arabia’s decision to continue its voluntary cut of one million barrels a day through the end of the year is expected to cause a slight decline in global oil inventories during the third and fourth quarters. This comes at a time when global demand is expected to increase by nearly two million barrels per day, likely to fuel China’s and India’s increasing consumption. Despite the cuts from OPEC, total oil supply is expected to increase by more than one million barrels per day in 2023 with further increases expected in 2024, which should bring the market back into balance. The gains are primarily coming from increased US production. The US is already producing a record 12 million barrels daily and is anticipated to eclipse 13 million barrels by 2024. This compares to the roughly 10 million barrels per day Saudi Arabia is capable of producing. All told, the world extracts about 100 million barrels per day and uses just as much. It’s a balanced but precariously fragile market where a minor 1% disruption in production could lead to a shortage of oil and significantly elevated prices.

Rapidly rising oil prices tend to raise alarms for economists because nearly all post-World War II recessions in the US were preceded, or accompanied by, a sharp spike in energy prices according to the St. Louis Fed.1 However, this view is largely influenced by the extreme fluctuations witnessed in the 1970s and 1980s following the creation of the oil cartel OPEC. In the wake of the 1973 Arab oil embargo, OPEC established a powerful grip on the global economy by wielding significant control over oil production and pricing. However, over the years, the landscape of the oil industry has evolved. The United States now claims the crown as the world’s largest oil producer and OPEC’s dominance has faced increased challenges. The emergence of new oil sources, notably shale, and the diversification of energy supplies have eroded OPEC’s once unassailable influence. While the cartel still plays a crucial role in oil markets, its ability to hold the global economy hostage has diminished.

Stay on Top of Market Trends

The Carson Investment Research newsletter offers up-to-date market news, analysis and insights. Subscribe today!

"*" indicates required fields

Today’s economy is notably different than it was five decades ago, rendering it more resilient in the face of rising oil prices. In the early 1980s, the Energy Sector accounted for a substantial 28% of the S&P500. In contrast, today it occupies only a 4% share in the index. During that era, other sectors, like Industrials and Materials, relied heavily on energy inputs, further amplifying the ripple effect of oil price fluctuations throughout the economy. This intricate web of interconnectedness left the world particularly vulnerable to the whims of oil prices.

Energy companies have also undergone a transformation over the past decade. At the turn of the century, oil and gas businesses operated with a wildcatter mentality, displaying a willingness to undertake substantial risks in pursuit of new oil and gas reserves. This approach was motivated by the rising oil prices observed in the early 2000s and the belief that substantial untapped reserves still existed. Governments and shareholders alike provided their support, leading companies to explore some of the world’s most challenging and remote regions. For some this daring approach paid off. Exxon Mobil discovered the giant Kashagan oil field in 2006, the largest oil field uncovered outside of the Middle East. However, many companies incurred losses, particularly those that heavily invested in U.S. shale exploration before the technology matured. Oil prices peaked at a staggering $147.30 per barrel in 2008, with global demand reaching 86 million barrels per day. Subsequently, the industry entered a prolonged downcycle characterized by overproduction and a wave of consolidation among companies.

Today, oil companies have shifted towards a more disciplined operating model. Investors are increasingly focused on the return of capital rather than funding the discovery of new reserves. These companies honed the technique for shale drilling and have embraced digital technologies, resulting in reduced operational costs and significantly enhanced profitability. Furthermore, they have dramatically reduced their debt burdens over the past three years after reaping windfall profits. With consensus expectations calling for Energy Sector earnings to grow at a low single digit rate over the next two years, we think there is upside on the table given the current price of oil.

01911714-0923-A