The Federal Reserve (Fed) reduced the federal funds rate by 0.25%-points at their December meeting, taking the federal funds rate to the 4.25-4.5% range. This was expected, but it was completely swept aside. The market reaction should give you a sense of how bad it was:

- The S&P 500 fell almost 3% on Wednesday (December 18th).

- The small cap index, the Russell 2000, fell 4.4%.

- There was little comfort in bonds either, with the Aggregate Bond Index falling 0.8%.

- This was on the back of interest rates moving up, with the 10-year yield rising from 4.4% to 4.5%.

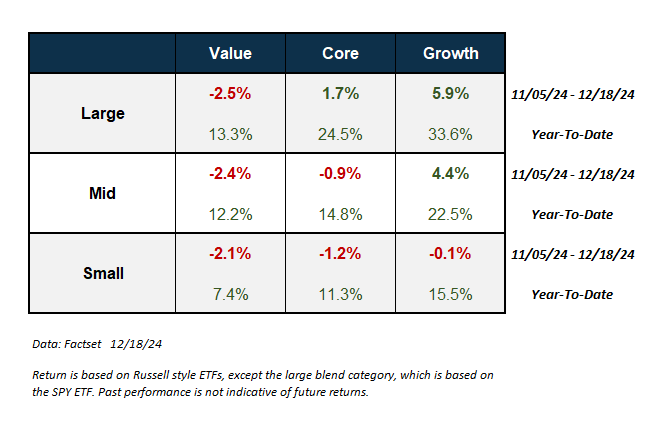

The fallout from the Fed meeting wiped out post-election gains across large swaths of the market, including value stocks and mid-cap and small-cap stocks, though looking back over the entire year, almost every major category is up double-digits so far, across style (value – core – growth) and capitalization (large – mid – small). For comparison the MSCI All-Cap World ex US Net Index is up just 7.2% year to date. That should tell you how strong of a year 2024 has been for US stocks, even with the recent pullback.

But let’s walk through why markets reacted so negatively to what the Fed did.

Higher Rates for Longer, Much Longer

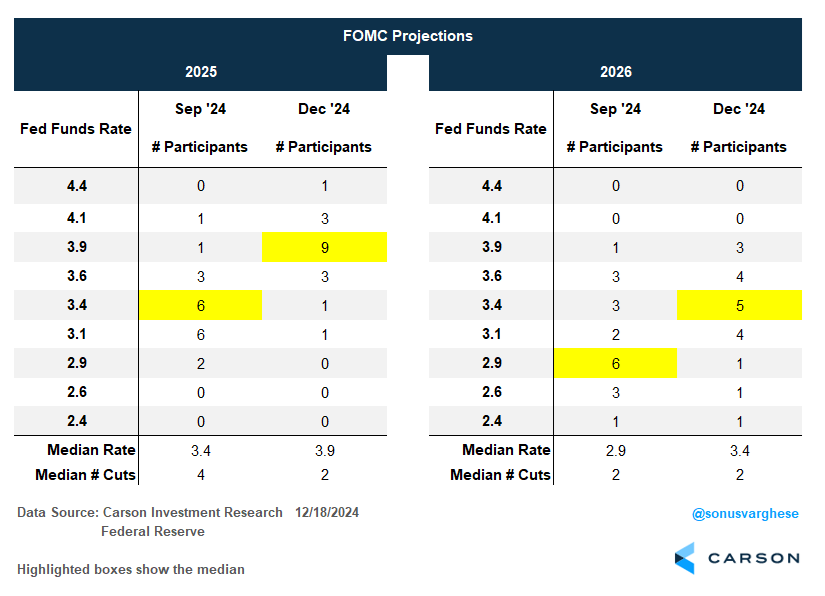

Every three months, the Fed updates their Summary of Economic Projections (the “dot plot”), which contains individual member estimates of the fed funds rate over the next few years, and estimates of economic variables (unemployment rate, inflation, GDP growth) under appropriate monetary policy. The last update was in September, and that was widely regarded as dovish. Not so this time around. We saw some big shifts in their thinking, especially with regard to where they estimate policy rates to be in 2025.

In September, the median dot projected the 2025 rate at 3.4%, implying 4 rate cuts (each worth 0.25%-points). In their latest update, they shifted that to 3.9%, i.e. just 2 cuts. The number of participants that are dovish relative to the median also dropped off significantly. Back in September, eight members projected 2025 policy rates below the median. The December median shifted 0.5%-points higher, and only 5 members are below it. That’s a big hawkish shift across the committee.

Neither did the Fed push the lost two rate cuts out to 2026. They estimated two rate cuts in 2026 in their September dot plot and stuck to that in their latest. With the 2025 median moving higher to 3.9%, that meant the 2026 rate estimate also moved up from 2.9% to 3.4%.

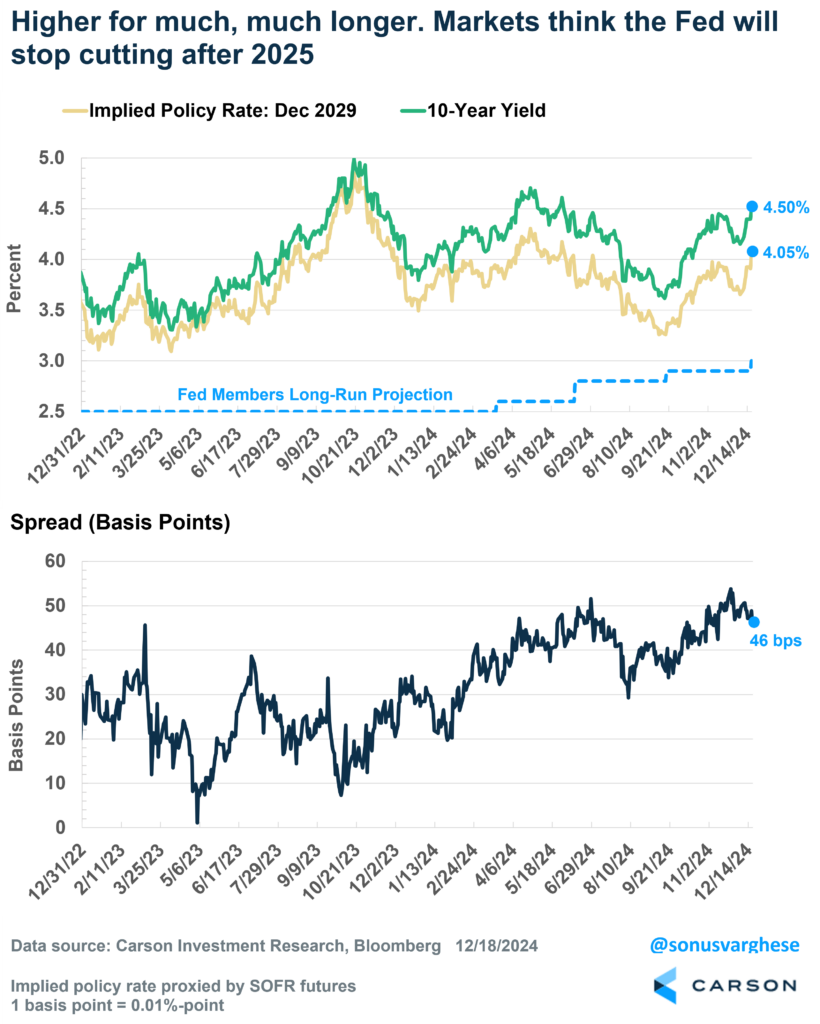

Interestingly, investors are even more hawkish than the Fed and are currently expecting the policy rate for 2025 to be just over 4%, and no cuts at all in 2026. In short, the economy and markets are looking at elevated interest rates over the next two years.

In fact, markets think interest rates will be elevated even going further out. Investors currently expects policy rates for 2029 to be at 4.05%, which implies investors don’t expect any rate cuts beyond 2025. That’s significantly more hawkish than the Fed. The Fed’s estimate of the long-run rate is at 3.0%. (It’s been gradually moving up from 2.5% over the course of this year.) This move up in estimates of long-run policy rates, by markets and the Fed, is a function of higher estimates of future economic growth (including productivity).

The 10-year Treasury yield can be thought of as a combination of 1) expected short-term policy rates in the future, and 2) a term premium, which captures uncertainty about supply and demand for US Treasuries and inflation uncertainty. A higher expected long-term policy rate should by itself drive the 10-year yield higher, which is what happened recently. But the term premium is also rising. I roughly proxy it here as the difference between the 10-year yield and the market’s implied policy rate for 2029. In 2023, when inflation was higher, it averaged about 0.2%-points. It’s now closer to 0.5%-points, perhaps driven by inflation uncertainty and higher expected deficit spending (which means there’ll be more supply of Treasuries on the market).

Long-term interest rates matter a lot. For one thing, an elevated 10-year yield means mortgage rates remain higher, and that’s not good for housing affordability. At the same time, elevated interest rates on the back of stronger growth expectations is not necessarily a bad thing. In fact, even for the Fed, December shifts in the dots came about as a result of:

- More optimism on the economy (though keep in mind that the Fed doesn’t have a GDP growth mandate)

- More comfort with where the labor market is

- Worries about inflation, and possible upside risk

The first two are positive, but the last one is curious given where the inflation data is.

The Fed Is Really Worried About Inflation Uncertainty

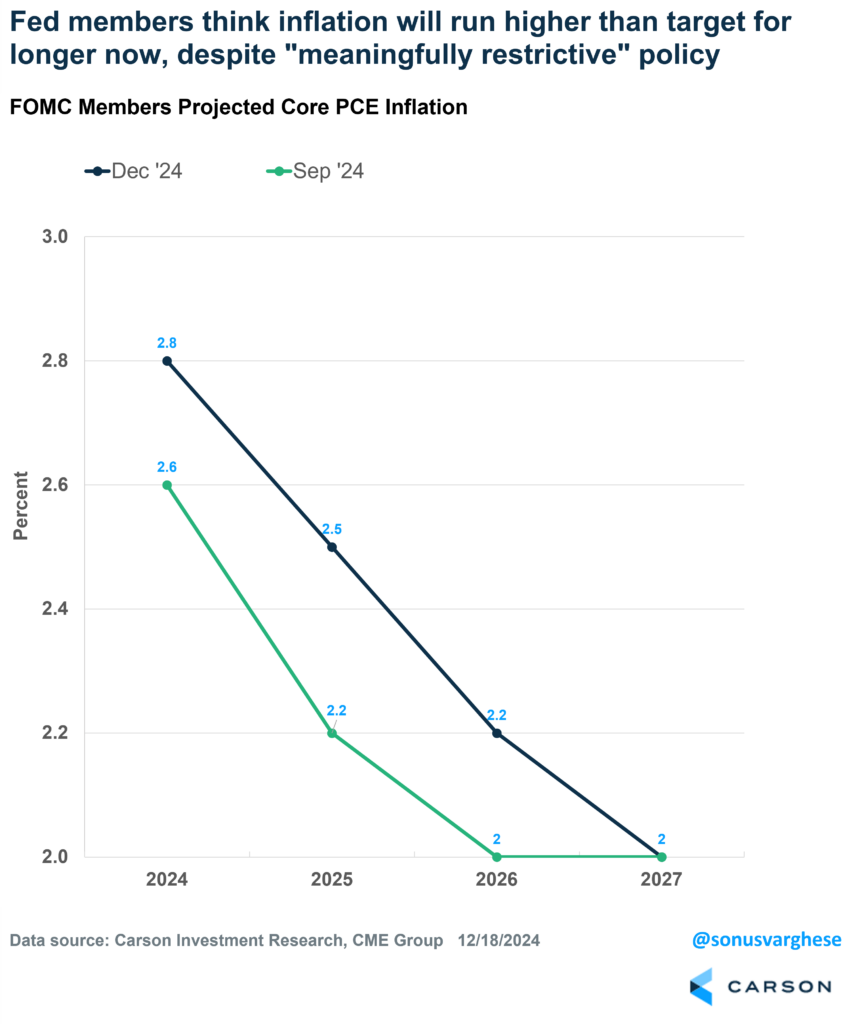

The Fed’s estimates for their preferred inflation metric, the core Personal Consumption Expenditure Index, was revised higher:

- 2024: Up from 2.6% to 2.8%

- 2025: Up from 2.2% to 2.5%

- 2026: Up from 2.0% to 2.2%

They expect to hit their target of 2% only by 2027 now. This explains why the dots moved in a more hawkish direction. But Fed Chair Jerome Powell struggled to articulate why they projected even two rate cuts in 2025 if they expected inflation to run at 2.5%, above their target. His answer was that policy would still be “meaningfully restrictive.”

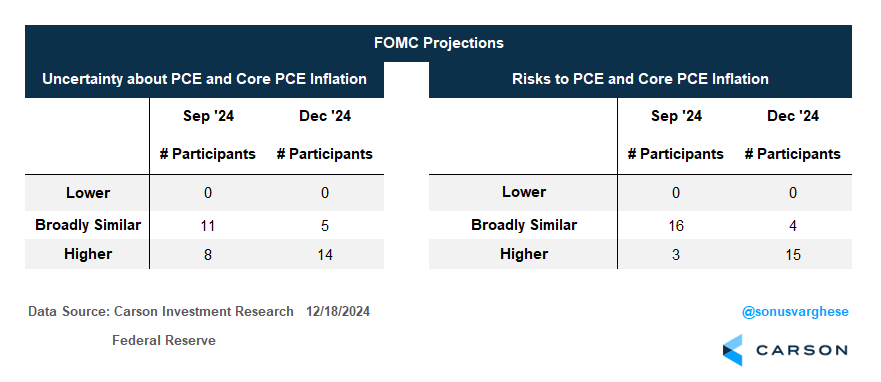

The Fed also thinks there’s much more upside risk to inflation now. In September, 8 of 19 members thought inflation uncertainty was higher, while 11 thought it was balanced (downside and upside risk about equal). Just 3 of 19 members thought inflation risks were “weighted to the upside.”

In their latest update, 14 of 19 members now think inflation uncertainty is higher. And 15 of 19 members think inflation risks are “weighted to the upside.” That’s a big shift, and clearly driven by two things: one, recent hotter-than-expected inflation readings in September and October (though November is expected to be quite soft); two, inflation uncertainty amid tariffs and deficit spending under the new Trump administration.

This is quite confounding to me. For one thing, PCE inflation is elevated right now because of lagging shelter data and financial services (thanks to portfolio management services inflation driven by higher stock prices). I wrote about this in a prior blog. Powell did say they won’t overreact to a couple of months of inflation prints but it seems like they’ve done exactly that.

Powell also mentioned that there’s considerable uncertainty about tariffs, including whether we’ll get any, the type of goods on which it’ll be imposed, the level of tariffs, and importantly, whether or not they’ll add to inflation (I wrote about how a rising dollar mitigates this risk). So it’s baffling that Fed members are accounting for this already. Also, deficits have been rising for the last year and half and during that time, inflation has pulled back, a lot. In fact, PCE inflation ran at an annualized pace of 1.5% in Q3 2024, while core PCE ran at 2.1%.

Small Measure of Solace: They Still Want to Protect the Labor Market

The one positive thing that came out of the Fed meeting was that they don’t want to see further cooling in the labor market even as they pulled down their estimates for the unemployment rate in 2025 (from 4.4% to 4.3%), which means the bar for tolerating any downside risk in the labor market is lower.

But there’s confusion even here. Powell noted more than a few times that the labor market is no longer a source of inflationary pressures. i.e. there’s no demand-side pressure since wage growth has eased (because labor market demand and supply are more balanced). Crucially, he said they don’t need further cooling in the labor market to get inflation to 2%. But this begs the question as to why they think meaningfully restrictive interest rate policy will drive inflation lower.

The pathway by which Fed policy operates is by creating lower demand in interest-rate sensitive areas of the market (like housing and manufacturing), which lowers demand for labor, creating more unemployment and lower demand-led inflation. But if they don’t want this to happen, and don’t think it’s even necessary, the question is why they’re keeping rates in restrictive territory.

I suspect we won’t find satisfactory answers anytime soon, at least not until the Fed is forced to make a larger-than-expected pivot to lower rates if the labor market deteriorates further (I wrote about these risks recently). To be clear, interest rates staying where they are is not likely to drive the economy into a recession, especially with income growth running strong. But elevated interest rates hit cyclical areas of the economy like housing and investment spending. I still expect the Fed to cut at least 2-3 times in 2025, but we may be on pause for an extended period, while hoping something doesn’t break in the meantime. That’s a recipe for elevated volatility as 2025 starts, a taste of which we got this week.

Stay on Top of Market Trends

The Carson Investment Research newsletter offers up-to-date market news, analysis and insights. Subscribe today!

"*" indicates required fields

For more content by Sonu Varghese, VP, Global Macro Strategist click here.

02560374-1224-A