So said Fed Chair Jerome Powell in his much-awaited Jackson Hole speech. The “job” in this case refers to getting inflation down to their 2 percent target. That was really the big story.

It really is about achieving price stability as Powell and company see it. In their view, without price stability the economy will not be able to achieve a sustained period of strong employment.

However, there are unfortunate costs. Powell admitted that getting inflation back to target will bring pain to households and businesses, amid higher interest rates, below trend economic growth and softer labor market conditions. But the failure to restore price stability is worse.

This is a very honest admission since the only real tool they have is interest rates, which impacts the overall level of demand in the economy. It is not a tool that allows for fine-tuning. But use it they will – to fulfill their responsibility to maintain price stability. They DO NOT want a repeat of the 1970s.

However, the path ahead is tricky.

A tough needle to thread

The Fed lifted interest rates by 200 basis points over just three months, taking it to the 2.25% -2.5% range (1 basis point or 1 bps = 0.01%). After the July meeting Powell said they thought rates have gotten to a moderately restrictive level.

And today, Powell said they expect to move to a sufficiently restrictive level to get inflation back to target.

Translation: they are going to continue raising rates.

But it also raises two big questions:

- What is the “terminal interest rate”, i.e. the highest rate they will get to in this cycle?

- And how fast do they get there?

After the June FOMC meeting, when they last put out assessments of appropriate monetary policy (via the “dot plot”), the median target rate for 2022 was 3.4%. The median target rate for 2023 was not much higher at 3.8%.

If they continue to raise rates by 75 bps at each of the remaining three meetings this year, interest rates would be at 4.50% -4.75% by year-end. Which would be higher than the maximum target estimated by any single member on the committee (the highest dot in the chart above).

We do not believe the Fed wants to get to that level. Recall that the June dot plot assessments came on the back of CPI inflation spiking to 9.1% year-over-year. Clearly there was some panic. The Fed did away with their prior forward guidance – that rates would increase at a 50 bps pace – instead choosing to raise rates by 75 bps in June and July.

They may yet revise their assessments higher in September. But even if you assume they want to get to a 4 % target rate by year-end, it implies a slowdown in the pace of rate hikes at some point this year. If it does not happen in September, it will happen in November and December.

But therein lies the tricky path they must navigate.

How do they convince the market that a step down from 75 bps to 50 bps is still a tightening of financial conditions, as opposed to a 25 bps cut?

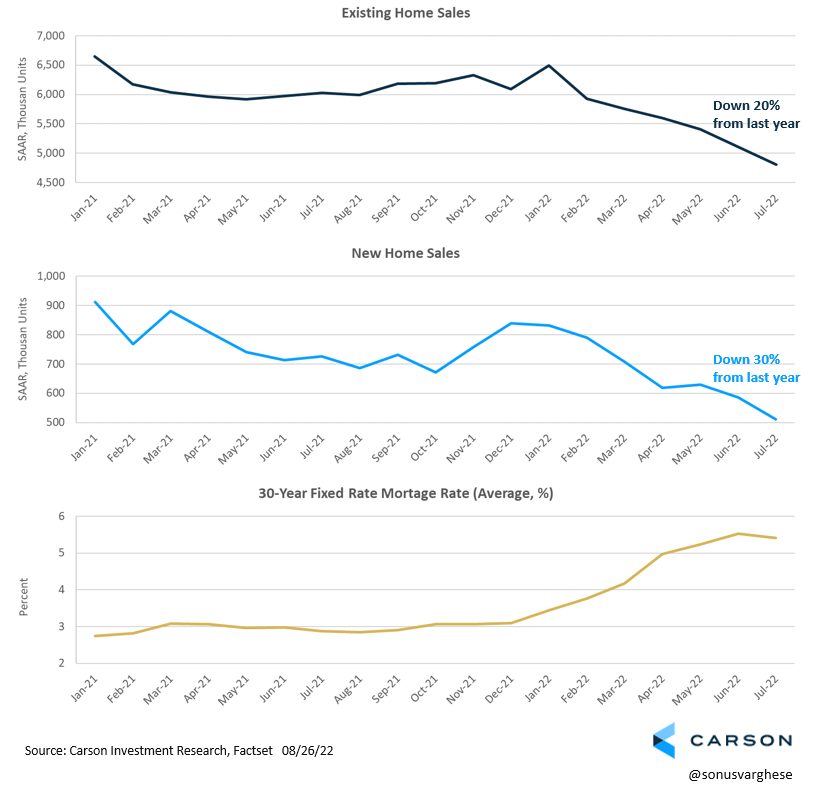

Up until July, aggressive rate hikes and hawkish comments meant financial conditions also tightened – which did a lot of work in slowing demand. The prime example is the housing market, where higher mortgage rates have resulted in significantly lower sales.

However, financial conditions have eased since July, as markets believed data dependency implied a quick pivot away from tightening. Softer economic data led markets to expect rate cuts in 2023. An easing of financial conditions means that some of the tightening conducted by the Fed has reversed.

Today, Powell pushed back hard on that.

While he did say another unusually large rate hike in September may be appropriate, i.e. 75 bps, he also noted at some point it will become appropriate to slow the pace. But more importantly, getting inflation back to target will require sufficiently restrictive policy for quite some time.

And that is how they are going to thread the needle. They will pivot, but it will be a pivot to pause as opposed to pivot to cuts.

In the initial phase of rate hikes what mattered was the pace, as the Fed took rates from extremely accommodative levels to moderately restrictive territory over just three months. But in this next phase, it will be the level that matters – with the Fed keeping rates at very restrictive levels for an extended period.

There will be no accommodation. At least not until inflation starts to move lower in a convincing way. But therein lies uncertainty.

Data dependency

Ultimately, the path of monetary policy is going to come down to the data, something Powell mentioned again today.

But inflation is easing.

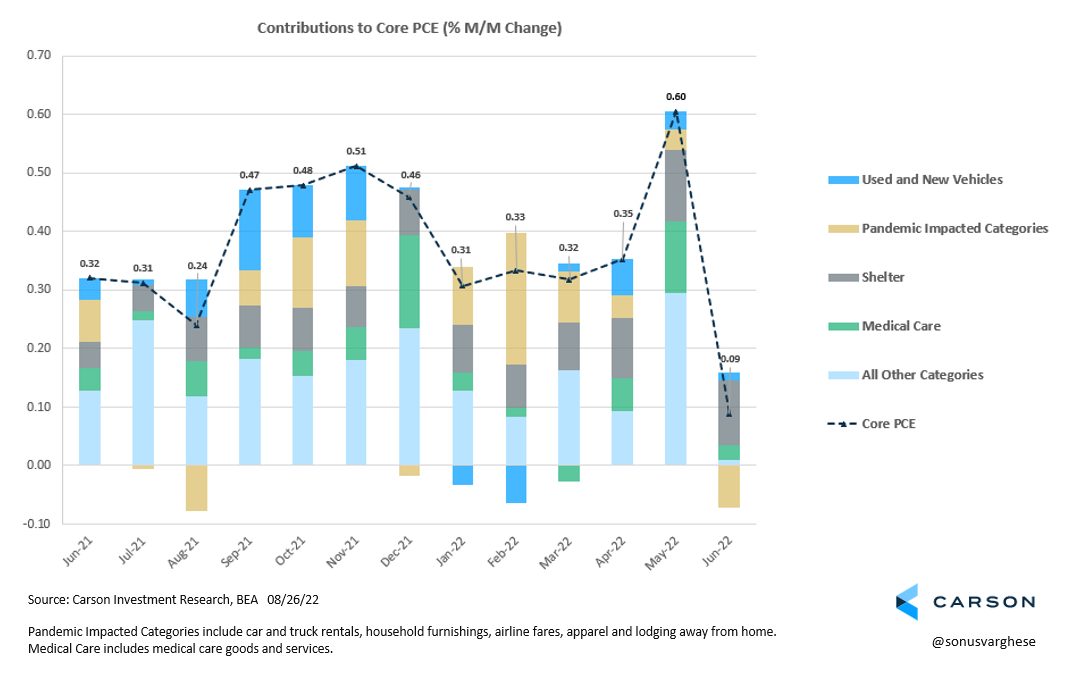

This morning the PCE price index (the Fed’s preferred inflation indicator) was reported to have fallen 0.1% in July. Core PCE, which strips out more volatile food and energy prices, was also much lower than expected, rising just 0.1% in July. The Fed typically uses core PCE to gauge the future path of inflation.

This is good news, but Powell was clear that one month of improvement is not enough.

The chart below illustrates how pandemic-impacted categories like airline fares, hotel prices, etc. are now imposing a deflationary force on core inflation. This is a big reversal from what we’ve seen over the past year, when these categories were driving inflation much higher.

Going forward, we expect used and new vehicle prices to also impose a deflationary force on inflation. Furthermore, it appears that housing inflation may have peaked.

Which means there is a high probability that core inflation falls quite rapidly over the next few months. Hypothetically, if core inflation rises at a 0.2% monthly pace over the final five months of this year, the year-over-year change in core prices would drop to 3.5% by December – down from 4.6% in July.

This would still be above the Fed’s target of 2% inflation, but we are curious whether this will lead them to a lower terminal interest rate. Of course, this could go the other way too, especially if energy prices surge again.

What we know for sure is that right now the Fed is clearly biased towards being more hawkish. This is a big shift from last year’s dovish bias, but the persistence of inflation caught them offside because of that. They have had to be aggressive to catch up, and they surely don’t want to be on the wrong side of inflation again. Once bitten, twice shy.

However, at some point they will shift. Especially if inflation falls faster than expected.

How soon and at what level? Only time, and data, will tell.

Final takeaways

To summarize quite simply,

The Fed is very committed to getting inflation back to their target, and there is a long way to go.

With that;

- The pace of interest rate hikes will eventually slow, which seems kind of obvious.

- The level of rates will stay higher for longer, i.e. a pivot to pause as opposed to pivot to cuts.

- Data dependency means markets will be parsing each data point for clues as to how high they will go and how long they’ll stay there.

So, we could see significant volatility ahead, as the data goes one way or the other.