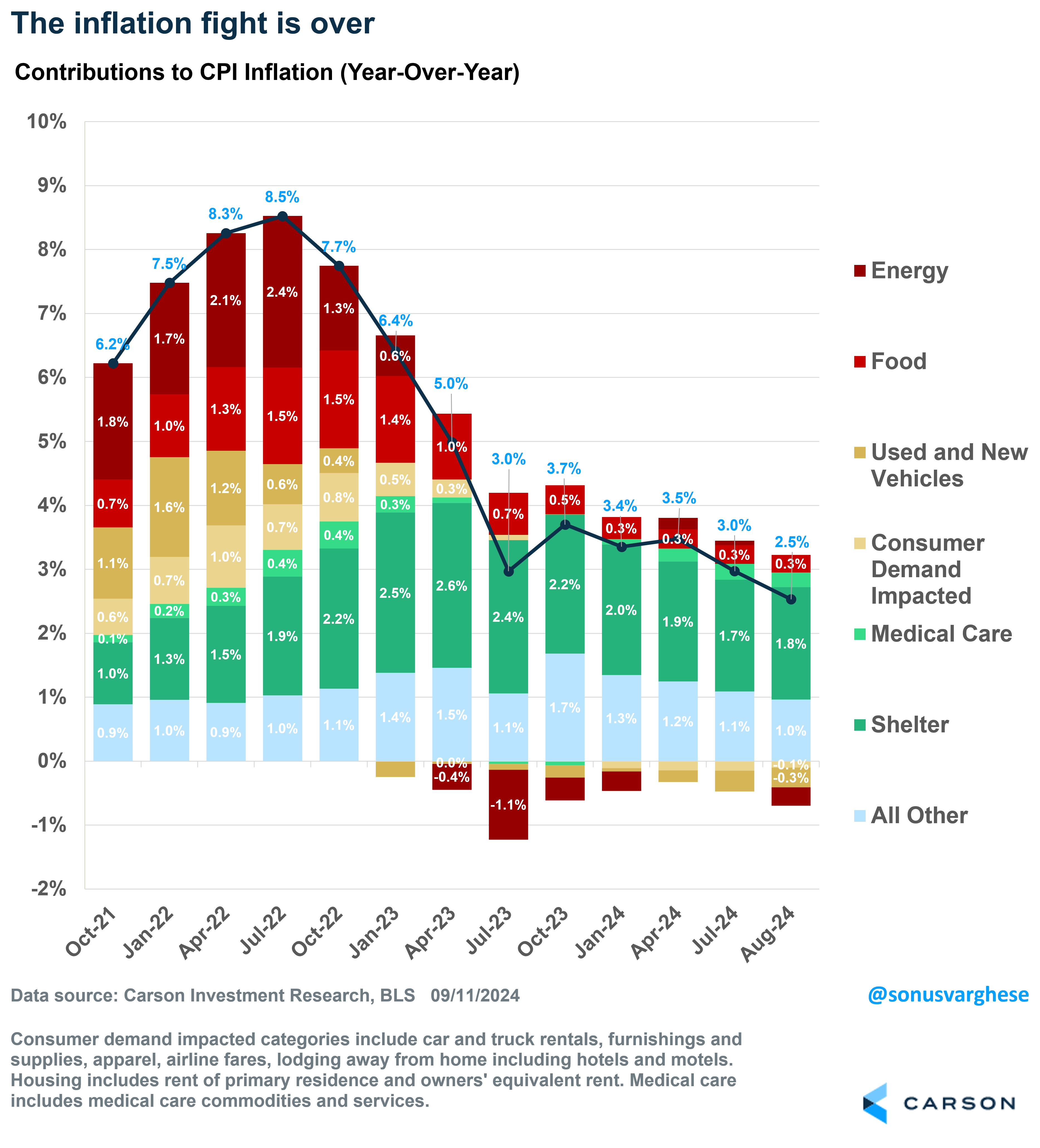

We’ve consistently said for several months now that inflation was last year’s problem. The latest consumer price index (CPI) data confirms this. Headline CPI is up 2.5% year over year (y/y) through August, which is the slowest pace in three and half years. Here’s some perspective on how far we’ve come:

- A year ago (August 2023), headline CPI was 3.7% y/y

- Two years ago (August 2022), it was 8.3%

- At the end of 2019, it was 2.3%

The inflation fight is done. This is welcome news for American households and even the Federal Reserve (Fed) as it seals the deal for the Fed to embark on a series of interest rate cuts over the next few months.

Stay on Top of Market Trends

The Carson Investment Research newsletter offers up-to-date market news, analysis and insights. Subscribe today!

"*" indicates required fields

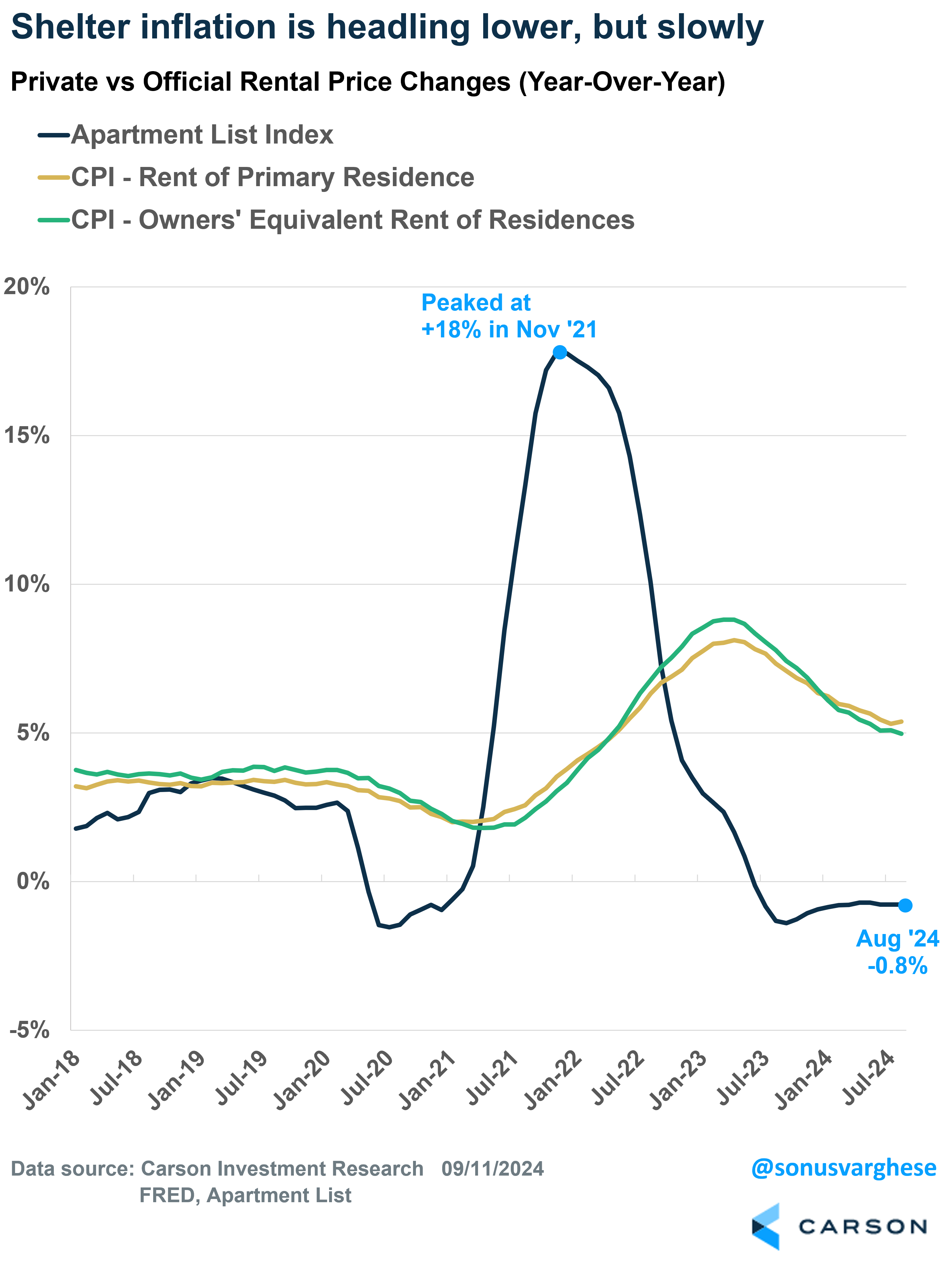

There’s actually good reason to believe that CPI data is overstating things. As you can see in the chart below, the big contributor to inflation is shelter, which is severely lagging more real-time private market data on rental inflation.

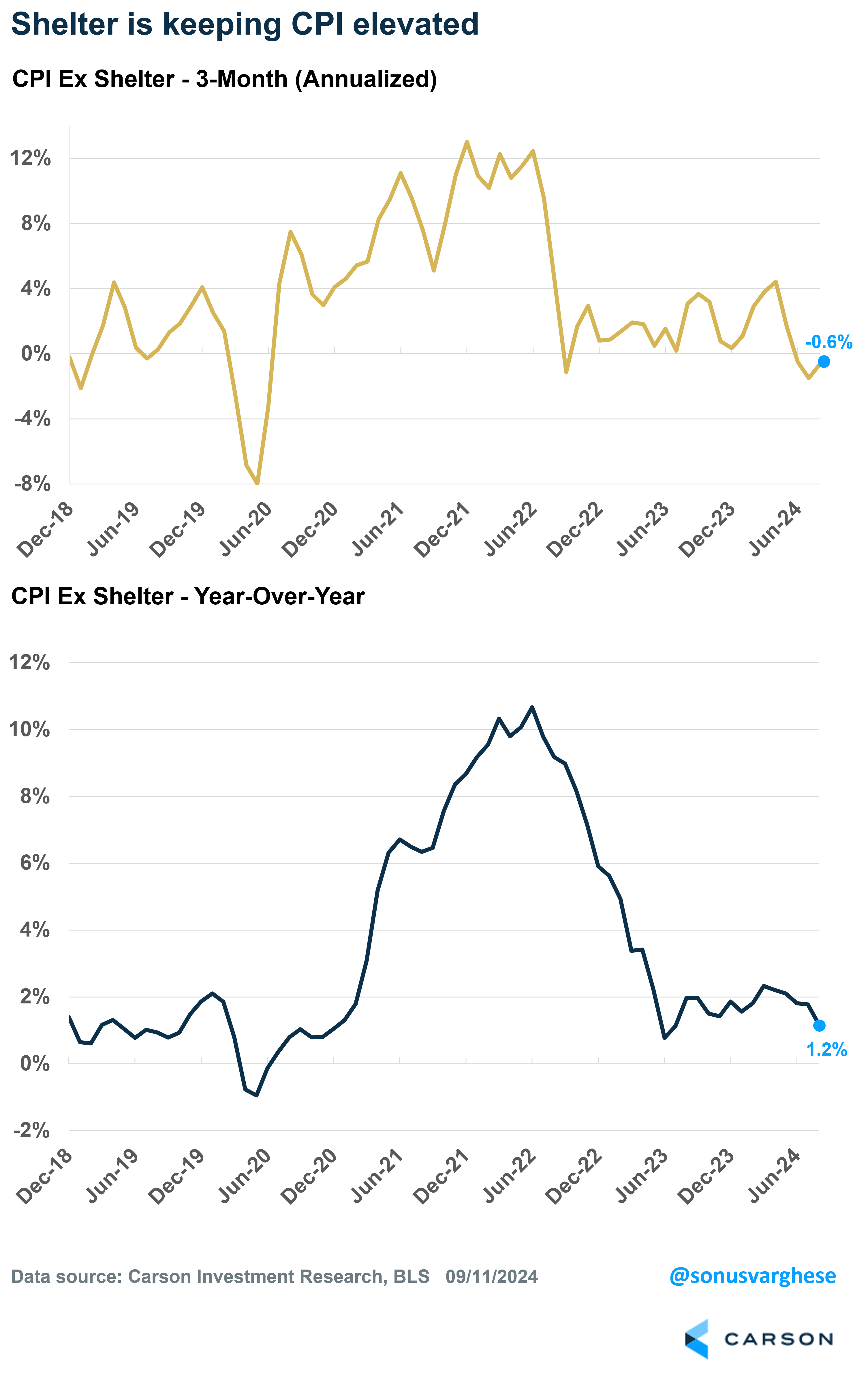

If you exclude shelter, inflation is running well below what we saw just before the pandemic hit, whether you look at short-term trends or the long-term trend. CPI excluding shelter is running at an annualized pace of 0.5% over the past three months, and it’s been in negative territory for the third month in a row. On a year-over-year basis, CPI ex shelter is up only 1.2%.

The problem created by lagging shelter inflation is magnified when you look at core inflation, which excludes food and energy. It’s the number the Fed typically likes to focus on. Core CPI is running at 3.2% year on year, with shelter contributing 2.2%-points of that. For perspective, at the end of 2019, core CPI was running at 2.3% year on year with shelter contributing 1.4%-points of that. In other words, the “excess” core inflation of about 0.9%-points we’re seeing now is coming almost entirely from the shelter component.

We’ve tackled the issue with official shelter inflation data a lot over the last couple of years. Shelter makes up 43% of core CPI, and the data runs with significant lags to what we see in actual rental markets. Rents of primary residence account for 10%-points of that, while “owners’ equivalent rent” (OER) accounts for the other 33%-points. OER is the “implied rent” homeowners pay, and it’s based on market rents as opposed to home prices. Private market data, like those from Apartment List, have been telling us that rents have actually been declining for over a year now. The good news is that official data is turning toward what the private data is telling us, but it’s happening ever so slowly. We’re not going to see the official data show outright deflation eventually, but it’s likely to stabilize around where it was pre-pandemic—it’s just going to take a while.

All Eyes on the Fed, but the Onus Is on Chair Powell

It looks like Fed members have gotten comfortable with the notion that the inflation fight is more or less over. The problem is that labor market trends are going in the wrong direction. I wrote about this last week. Note that the Fed has two mandates: low and stable inflation, along with maximum employment. At this point, they’ve mostly achieved the former, but the latter is clearly at risk.

What is worrying is that several Fed members have talked about cutting rates in a “gradual,” or “careful,” or “prudent” manner, indicating they don’t see any urgency to get ahead of declining labor market trends. Meaning they are inclined to start with a 0.25%-point cut at their September meeting next week and proceed at that pace over the remainder of the year. The slightly hotter core CPI data from August, albeit on the back of lagging shelter inflation, further reduces the odds of them starting the rate cut cycle with a big 0.50%-point cut. But this also makes it even more likely that they find themselves further behind the curve in a few months and will have to play catch-up by going big later on, a rerun of when they waited too long to raise rates as inflation was picking up in late 2021/early 2022—but from the opposite side.

A notable exception to the gradualist approach appears to be Fed Chair Jerome Powell himself. At his Jackson Hole speech about three weeks ago he made no mention of following a “careful” or “gradual” approach. Instead, he said they would not tolerate further cooling in the labor market. Since then, we got a slew of labor market data, including August payrolls, showing things are slowing down further. There’s a reasonable chance that Powell may buck the opinion of other Fed members and decide to “go big” with a 0.50%-point cut at their September meeting. That will also show intentionality that they do intend to support the labor market—and hence the economy, since incomes drive consumption.

While the economy is in a reasonably healthy place today, that may not be the case 6-12 months from now if the Fed starts to fall further behind the curve. Safe to say we’re not in a recession now, nor is one imminent over the next few months, but the odds of one by mid-2025 is starting to increase. This raises the stakes for the Fed’s September meeting and all eyes will be on Chair Powell.

For more content by Sonu Varghese, VP, Global Macro Strategist click here.

02405888-0924-A