Risk vs. reward. How do we balance both? Consider the child who calculates whether sneaking a cookie from the cookie jar is worth the risk of getting caught by an angry parent. Or the adventurer who knows the risks of scaling a tall mountain, but imagines the reward of reaching the highest peak.

The risks associated with investing can be just as scary and the rewards just as gratifying. The risk-return tradeoff can be encapsulated by the common saying, ‘no risk-no reward.’ At Carson we like to say, ‘volatility is the toll we pay to invest.’ Regardless of how it is phrased, the underlying assumption is the same. When seeking higher profits, an investor must be willing to accept a higher possibility of losses.

In the stock market, risk is typically measured in terms of volatility. A common measure of volatility is standard deviation. Standard deviation is a measure of how data is dispersed in relation to the mean, or average. In simple terms, a lower standard deviation indicates that the price of a stock does not fluctuate as dramatically as a stock with a higher standard deviation.

Another measure of risk for stocks is beta. While standard deviation can be characterized as the absolute risk of a stock, beta is a measure of relative risk. Beta measures the expected increase or decrease of a stock in proportion to the stock market as a whole. It’s systematic risk. In theory, a beta greater than 1 indicates more volatility than the market, while a beta less than 1 indicates less volatility than the market.

Regardless of the risk measure used, a higher number would indicate the expectation of a higher return. More risk should equal more reward. This is exactly what is postulated by the capital asset pricing model (CAPM). Using CAPM, an expected rate of return can be calculated for a stock based on its riskiness relative to the rest of the market (beta).

Developed in the late 1960s, CAPM predicts a positive and linear relationship between risk and return. On average, more risk equals more return. Empirical tests carried out since have challenged this theory, including a study by Robert Haugen and James Heins (1972) which showed that low-beta stocks in the United States outperformed in the period from 1929-1971. Essentially a low-volatility anomaly.

An anomaly exists in financial markets when a security, or group of securities, performs contrary to what would be predicted by a model such as CAPM. Since the original Haugen and Heins study, evidence for, and the persistence of, the low-volatility anomaly has been well documented by both academics and investment professionals. Not only within the United States, but also across global stock markets.

Stay on Top of Market Trends

The Carson Investment Research newsletter offers up-to-date market news, analysis and insights. Subscribe today!

"*" indicates required fields

Why may this be the case? One explanation is rooted in behavioral finance. The ‘lottery effect’ states that at times, investors are more willing to chase high-beta names (stocks with higher market risks) after they have spiked in price, to achieve lottery like returns. Simply stated, even if the probability of winning is low, the chance at a large payout is too enticing to ignore. The increase demand on these high-beta names pushes prices up artificially, potentially decreasing future returns.

Other theories exist including the inability or unwillingness to short high-risk stocks, the oversized attention high-risk stocks tend to receive in the media, which can attract buyers, and asset managers who tend to tilt toward high-risk stocks in an effort to beat performance benchmarks. Then there is just simple math.

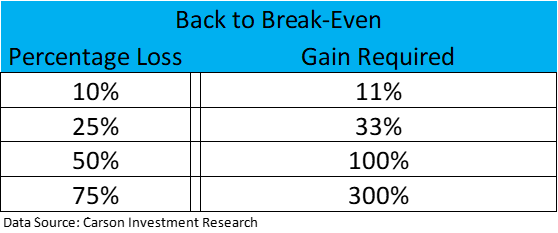

While low-volatility stocks tend to lag during bull markets, their defensive characteristics mean they tend to outperform during bear markets. As the table below shows, a stock that loses 50% of its value has to subsequently return 100% just to get back to even. While a stock that loses 25% of its value only has to return 33% to get back to even. This helps to explain how a low-volatility portfolio can keep pace over a full business cycle.

This smoother ride is the primary objective of low-volatility strategies. For risk-adverse investors, smaller drawdowns can provide confidence to stay invested in equity markets during difficult periods. Additionally, low-volatility strategies tend to be less correlated with broader-based equity strategies, enhancing their diversification benefit in a larger portfolio.

Assessing and balancing risk vs. reward is important in all aspects of life, not just investing. In doing both, the ethos typically has been more risk brings a greater chance for more reward. For stocks anyway, the low-volatility anomaly challenges that notion.

02355039-0824-A