Being an effective stock picker is a specialized skill that requires a combination of deep knowledge of a company’s business model and prospects, fierce self-discipline, a hard-earned feel for market psychology, and knowledge of portfolio construction to help limit risk. In the end, you need to have an informational advantage that isn’t already “priced in” to the market. (The market collectively is pretty smart but not all-knowing.)

Also, since it’s easy to invest in the “average” stock these days through index-tracking funds, stock picking is basically a zero-sum game. For every winner who picks an above-average stock, there’s a loser who picks a below-average stock. And you’re competing not just against the general public, but large institutional investors.

Stay on Top of Market Trends

The Carson Investment Research newsletter offers up-to-date market news, analysis and insights. Subscribe today!

"*" indicates required fields

Stock picking is hard to do well, but there are people who are successful. Just realize that they are relatively rare. It’s healthy for us to believe in our own minds that we have the unique combination of street smarts and common sense that may give us the ability to stay ahead of the markets. But it’s even healthier to understand that almost everyone believes that. Of course, some of them will be right, but many will be wrong. Thankfully, we can avoid the problem altogether and still participate in broad markets through a well-diversified portfolio.

Risk Matters

Just by the numbers, it’s easy to see the risk involved in stock picking. Outside of a diversified portfolio, individual stocks, even the more stable ones you might find in the S&P 500, are incredibly volatile. Why? Every stock’s price is influenced by the broad economy. That more systematic risk is reflected in the risk of the broad index. But a lot of the risk in an individual stock is idiosyncratic to the particular company, from their strategy, their leadership, their funding strategy, and a myriad of other factors.

One of the basic principles of investing is that you want to be compensated for higher risk with a higher expected return. The high risk of a single stock within a broader portfolio will be somewhat diversified (depending on the size of the position and what’s in the portfolio), but probably not as much as many people think.

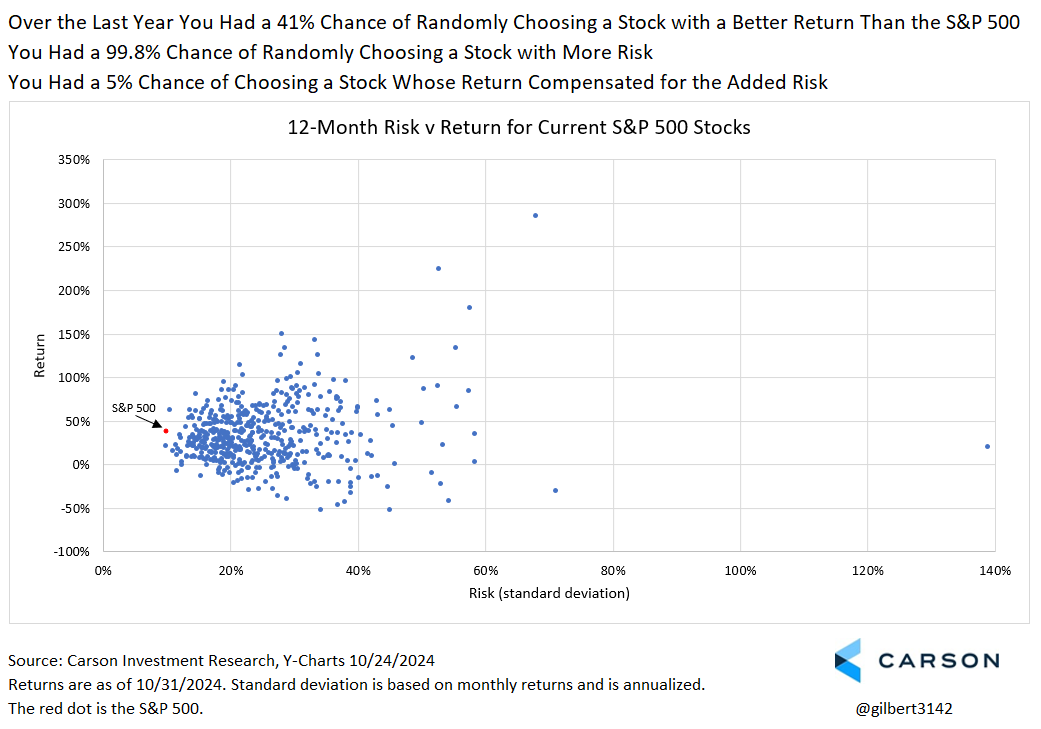

Here are some numbers to bring the point home. As of the end of October, there were one-year returns available for 498 current S&P 500 stocks. Of those 498 names, 497 were riskier (more volatile as measured by standard deviation) than the S&P 500 Index. (For the curious, General Dynamics was the exception over that time period.) At the same time only 204 names, or just over 40%, had a higher return. Finally, only 5% were more risk efficient than the S&P 500 (outperformed their expected return given their level of risk). That super risky dot way off to the right that made me make my chart much bigger than I wanted to? That’s Super Micro Computer.

Be Disciplined

If picking stocks is interesting or entertaining for you and you’re genuinely comfortable losing your investment (not saying you will, but you need to accept the possibility), then it may make sense. But even doing that takes discipline, because “fun” stock picking always has some risk of turning into something worse if the money at risked starts to get out of bounds. Most people are by nature generally risk averse when investing. Gambling, though taps into a part of our brain that’s risk seeking. It’s important not to confuse the two.

Be Brutally Honest with Yourself

I did a little experiment at one point in my career where I had colleagues share their market views on a quarterly basis. It wasn’t the purpose of the exercise, but one thing that allowed me to do is to check the record when someone said, “My view last year was X and I was right.” Most of the time someone said that, they in fact were correct. I had thoughtful colleagues. But I was still surprised with the number of times people remembered having one view when in real time they said the opposite. Our memories have a tendency to put ourselves in a good light, and that’s not a bad quality to have. But when investing, it can do some damage.

Also realize that usually we only hear (or tell) the good stories, the stories of our successes. Nobody is going to make a movie about someone who invested heavily in GameStop at the wrong time and lost most of their savings. People share their wins. Just recognize that most of the negative stories out there you just don’t hear about.

Finally, sometimes ownership of a concentrated stock position is not up to us. It may be part of our compensation or a business sale. The same general principles apply. Financial advisors can provide options for diversifying some of that risk.

Happily, we don’t need to be stock pickers to be investors. There are vehicles both for getting the potential benefit from stock selection inside a well-diversified portfolio or for simply getting exposure to a broad index. Either way, there’s much to be thankful for this year when it comes to markets. We wish everyone a Happy Thanksgiving.

For more content by Barry Gilbert, VP, Asset Allocation Strategist click here.

02527436-1124-A