On February 1st, President Trump signed executive orders (EO) imposing tariffs on Canada, Mexico, and China, effective 12:01am February 4th. The orders included:

- 25% tariffs on Canada, apart from energy imports (tariffed at 10%)

- 25% tariffs on Mexico

- 10% tariffs on China

These tariffs applied to all goods and would be over and above existing tariffs, including “de-minimus” goods. That means even a small gift bag sent from Toronto to Chicago would be subject to tariffs, not to mention small packages from China. (That’s one way a lot of Chinese exporters got around existing tariffs.) The White House placed some conditionality on these tariffs, including improvement in the immigration situation and improvement in the drug (fentanyl) situation.

These tariffs are a big deal, since it’s universally applicable across goods coming from America’s three largest trading partners, which is why markets reacted quite negatively as soon as trading started last Sunday night. However, the good news is that there was a big reprieve on Monday, as the White House hit the pause button on both the Mexico and Canada tariffs. Equity markets recovered from losses, though they closed the day lower (the S&P 500 fell about 0.8% on Monday, February 3rd). The Canadian dollar and Mexican Peso fell over 2% after the tariffs were announced, but more than recovered after the tariff pause announcements on Monday, eventually ending up with slight gains against the US dollar.

Canada and Mexico Tariffs Paused, but There’s Still Cloud Cover

The 25% tariffs on Canada and Mexico were paused by President Trump for 30 days. This was after conversations he had with the heads of Mexico and Canada on Monday.

President Claudia Sheinbaum of Mexico said they reached a series of agreements to pause the tariffs, including, reinforcing the border with 10,000 Mexican National Guardsmen to counter drug trafficking. The US is expected to prevent trafficking of high-powered weapons into Mexico.

Stay on Top of Market Trends

The Carson Investment Research newsletter offers up-to-date market news, analysis and insights. Subscribe today!

"*" indicates required fields

The pause on Canadian tariffs came later in the day, after two phone calls between Trump and Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau. Canada will spend about $680 million on border security, pushing ahead with plans that have been in the works. In addition, they will also appoint a “fentanyl czar,” list cartels as terrorists, ensure 24/7 eyes on the border, and launch a Canada-US joint strike force to combat organized crime, fentanyl, and money laundering.

But this isn’t over.

For one thing, teams from Canada and Mexico need to work with US negotiators to secure a security and trade deal over the next month. Therein lies the rub, as Trump will clearly expect trade concessions from both parties. Security arrangements will likely also need to be quantified and ensure mechanisms for verification. Trade is relatively “easier” to measure, but even here, it’s not simple. China reneged on the “Phase 1 Trade Deal” they signed during Trump’s first term in office, falling well short of their commitments to buy US goods.

Second, the 10% tariffs on Chinese goods went into effect at midnight on Tuesday. These are not as big as those proposed on Canadian and Mexican goods, but it could still be significant for some sectors (including smartphones and computers). China retaliated with tariffs on US coal, gas, and other goods — but these are not that significant, and perhaps indicates China’s willingness to negotiate. As with Mexico and Canada, there may be a temporary reprieve if Trump and President Xi of China have a fruitful talk.

Third, Trump’s next target is likely Europe. Expect more announcements on this front in the upcoming weeks. Unlike Mexico and Canada, both China and Europe may be less incentivized to reach a quick deal (they may not have much to offer anyway).

These Tariffs Are a Big Deal

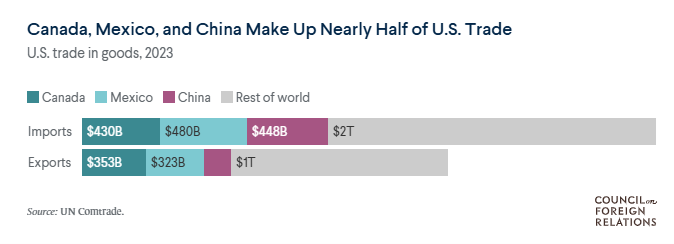

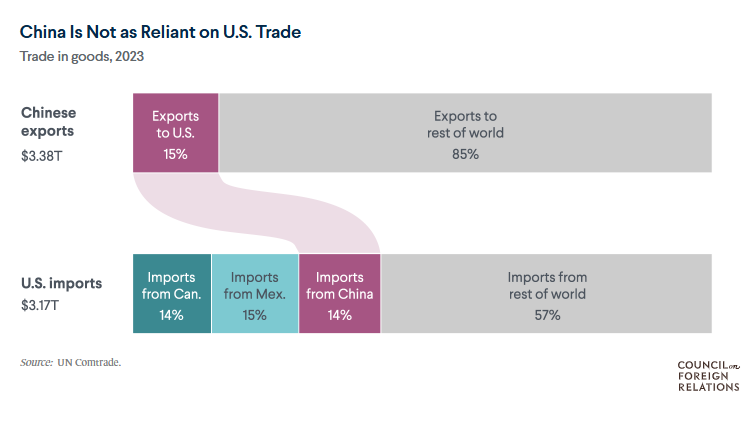

These tariffs, assuming they are imposed, are significant. Even if it doesn’t happen, the cloud of uncertainty is something businesses will have to deal with. If it does happen, that would be quite a massive shock — much larger than all the trade actions taken in Trump’s first term. Canada, China, and Mexico make up about 43% of US goods imports, and about 41% of US export destinations, as this chart from the Council of Foreign Relations (CFR) illustrates.

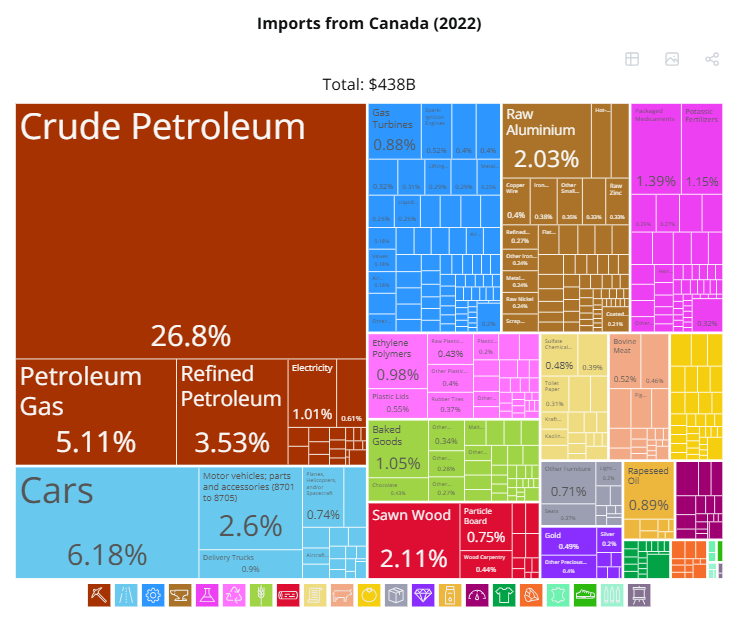

An immediate problem is oil and gas, which is especially salient for inflation and the Federal Reserve (Fed). The US is the largest producer of oil in the world. However, it mostly produces “light, sweet” crude oil. But US refineries, which refine oil into gasoline/diesel/etc., require “heavy” crude, which it imports from other countries. Especially Canada. The US’s biggest import from Canada is crude oil and other petroleum products, making up over a third of Canadian imports.

There’s a reason why the Trump administration chose to impose only 10% tariffs on Canadian energy. Prices are still likely to go up. 10% tariffs translate to ~ $6/barrel on Canadian crude, equivalent to about 14 cents/gallon. However, the impact is going to be quite localized, with the Midwest more likely to be impacted. Areas in New England may also see higher electricity prices (for example, Maine imports 100% of its heating oil from Canada).

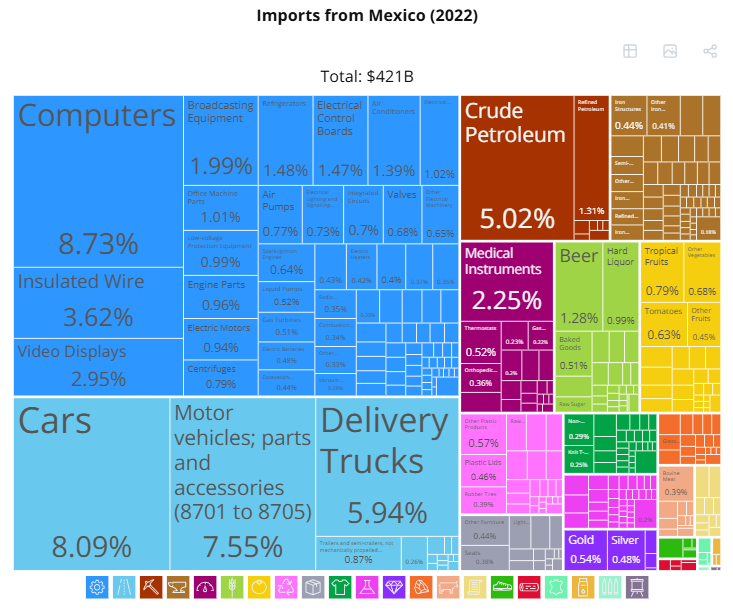

This will also be a huge blow to the North American auto industry. Vehicles and parts make up the largest portion of imports from Mexico, at about a fifth of all US imports. In reality, there really is no US-Canada-Mexico trade. Instead, it’s all one big zone, i.e. North America. This is especially true for the auto industry. Cars/trucks and various parts move across supply chains situated across all three countries, and sometimes cross borders multiple times.

In fact, a lot of the content in Mexican motor vehicle exports to the US originates in the US. Ultimately, a 25% tariff on Mexico and Canada will raise production costs for automakers, potentially adding up to $3,000 to the price of 16 million vehicles sold in the US. Most automakers are significantly exposed to Canada and Mexico tariffs hitting their plants. About half of the cars and light trucks exported by Mexico to the US in 2024 were made by the Big 3 in Detroit.

Mexico is also America’s largest source of imported fresh fruits and vegetables. The 25% tariffs will hit all this produce at the worst possible time, since winter is when the US relies most on imports.

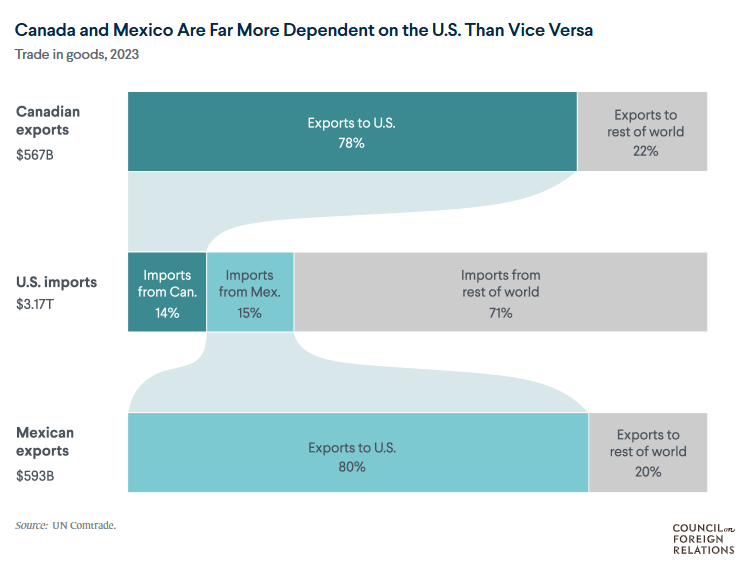

All this also tells us that Mexico and Canada are especially reliant on trade with the US, rather than the other way around. Trade makes up ~ 70% of both economies’ GDP. About 80% of Mexico’s exports come to the US, while about 70% of Canadian exports come to the US. Whereas exports are not a significant piece of the US economy. This asymmetric dependency is perhaps what Trump is hoping to leverage — to get them both at the table, and extract concessions.

China Could Be Tricky

China is less dependent on the US. Trade (imports + exports) makes up less than 40% of the Chinese economy, much lower than about 60% just two decades ago. Trade with the US has also pulled back significantly, especially areas which were hit by tariffs in 2018-2019, though China got around these by increasing trade with countries like Vietnam, and even Mexico. In fact, China’s share of global trade has actually increased by about 4% since 2016. All this means the US has much less leverage over China, relative to Canada and Mexico. But this is why there is a possibility of seeing universal tariffs. That way China can’t get around US tariffs. And why these first set of tariffs may not be the last ones we see.

In 2018, the Chinese retaliated in several ways, zeroing out soybean imports from the US for a year (hitting states like Iowa), adding tariffs on all other US agriculture imports, and halting purchases from Boeing. Another thing to keep an eye on will be their currency. Unlike the CAD and the Peso, Chinese authorities control the Renminbi. After the trade war started in February 2018, the Chinese renminbi fell about 14%. China’s currency is currently trading even below 2019 lows, and it’ll be interesting to see where Chinese authorities fix their new level over the next several days.

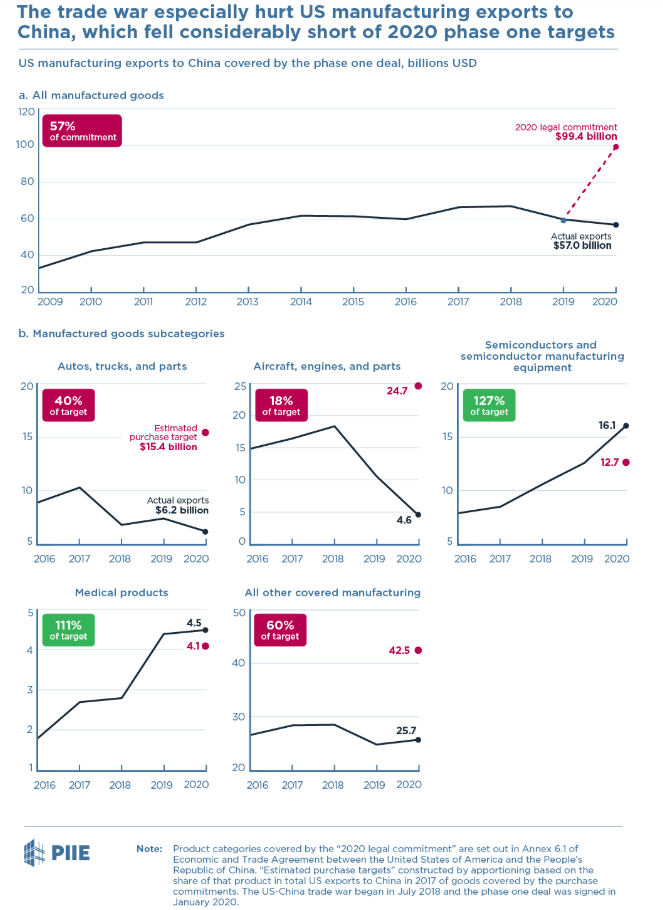

With respect to any “deal,” that would have to come after extensive negotiation. This is what happened in 2018. Moreover, China did not meet the terms of the deal. Far from it, in fact. As part of the “Phase 1 Deal” signed on January 15th, 2020, China was supposed to buy an additional $200 billion of US goods. As the Peterson Institute has detailed, China fell well short of this, buying only 58% of the US exports it committed to purchase over 2020-’21.

China purchasing manufactured goods were a key piece of that deal, making up 70% of the value of all goods covered by purchase commitments. Again, they were even further below commitments in this area. US manufacturing exports to China nearly doubled between 2009 and 2017. Then it flattened in the second half of 2018 and fell by 11% in 2019 (partly due to retaliation against Trump’s first round of tariffs). But even after the Phase 1 deal, US manufacturing exports fell another 5% (2020), falling 43% short of the legal commitment for 2020, and 12% below pre-trade war levels.

The US is going to need stricter enforcement mechanisms this time around, which is going to make things even harder. Or we get a rerun of what happened after the last trade deal with China. All of this will take time to play out.

Will These Tariffs Hit Inflation?

It’s hard to answer this question in a definitive way, because there are so many things intertwined with tariffs, including retaliatory measures, currency changes, demand shifts, and supply dynamics.

All else equal, tariffs are a tax, and that means prices will go up. Note that tariffs will send the price level higher. But technically, a one-time increase in the price level is not inflation. Prices would have to keep going up for higher inflation, which would only happen if tariffs kept ratcheting higher. But as the 2024 election showed, consumers care a lot about price levels even if inflation is low.

Goldman estimates that higher tariffs on Canada and Mexico raises the effective tariff rate by 7%-points, implying a 70 bps increase in the core Personal Consumption Expenditures Index (core “PCE,” the Fed’s preferred metric of inflation), and a 0.4% hit to GDP. Existing China tariffs already contribute 0.3% to core inflation (core PCE is currently up 2.8% year over year).

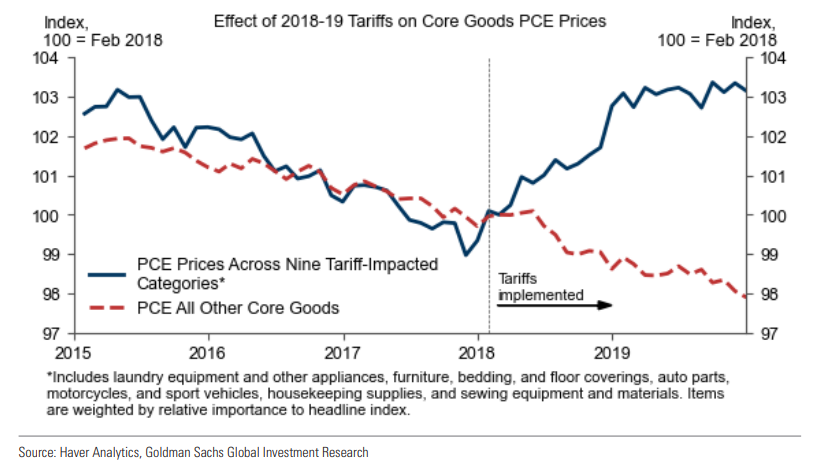

However, we don’t know any details yet, and all else is never equal. Let’s look back at 2018 once again.

Core PCE inflation ran around 1.8% annualized in 2018-’19, below the Fed’s target of 2%. So it’s natural to think that the 2018-’19 trade war didn’t have any impact on price. However, this is not the case. Prices in tariffed categories rose by almost exactly the amount of imposed tariffs , just as you would expect. However, we were already in a downtrend for core goods inflation prior to the tariffs being imposed, which continued for non-tariffed goods and offset the overall inflationary impact.

Another dynamic in play in 2018-’19 was that companies did not pass higher input costs onto customers (a lot of those tariffs were on “intermediate” goods). But we may be in a different dynamic now, where companies feel like they can pass higher costs to consumers. That’s what they did in 2021-’22, even as they maintained their own margins (and even expanded them). In fact, Raphael Bostic, the Head of the Atlanta Federal Reserve, recently said that leaders at companies he speaks to said they would pass higher costs through “100 percent.”

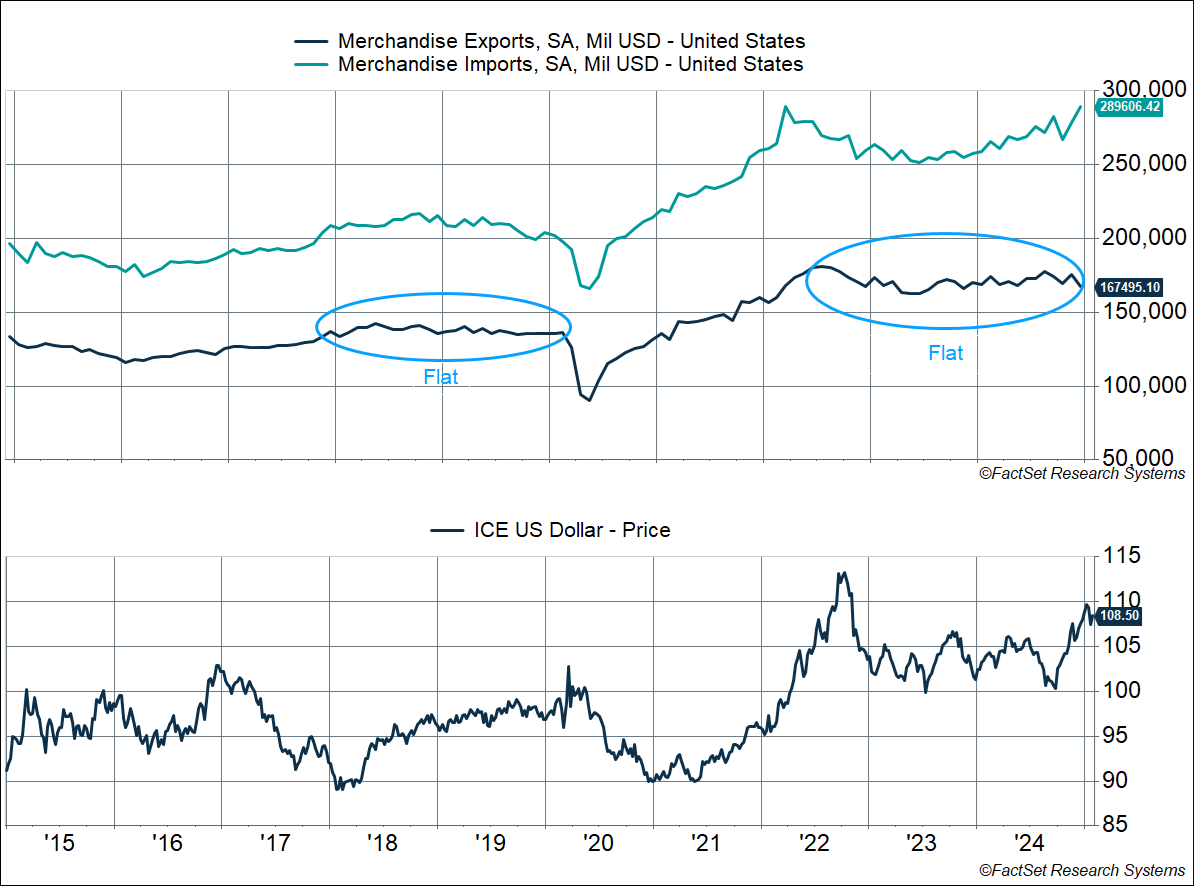

Tariffs Are Likely to Hurt US Manufacturers

Ultimately, the 2018-2019 trade war hurt US manufacturers. The trade war meant US manufacturers already started down a hole, thanks to retaliatory tariffs and a strengthening dollar. US goods exports were flat across 2018-2019. On top of that, China also failed to live up to its commitments to buy US manufactured goods, as I discussed above.

It’s likely the same happens again. The dollar has already been strengthening, rising almost 9% since the end of September — a big move over a fairly short period of time (4 months). As we wrote in our 2025 Outlook, the strong dollar does two things:

- It mitigates some of the inflationary impact of tariffs

- It makes US exports more expensive

Over the last two years, exports have been flat amid an elevated dollar. Q4 2024 was especially bad — real goods exports fell 5% (annualized), pulling real GDP growth down by 0.4%.

Market Impact – The Fed Doesn’t Like Uncertainty Either, and That’s a Problem

As I pointed out earlier, it’s going to take a while to understand any inflationary impact of the tariffs, assuming they even happen. Given the methodology of inflation metrics, it’s going to be months before we have any understanding of the impact.

However, that creates a problem, as it could push the Fed to sit on an extended pause. Thus, keeping rates elevated longer may be needed, raising the odds that something breaks.

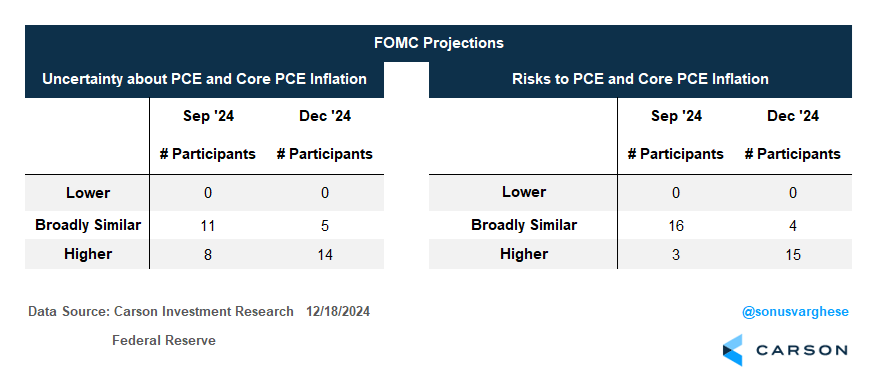

I just wrote a couple of weeks ago after positive CPI data that the inflation outlook still looks good. Powell himself said the same thing after their meeting last week. He was surprisingly positive about the inflation outlook. At the same time, the Fed is increasingly concerned about inflation uncertainty. That is why they got hawkish in December. In the first post-election Fed meeting, they cut rates by an additional 0.25%, but their dot plot projections showed just 2 cuts in 2025 (versus the prior projection of 4 cuts). Also included in the dot plot, 14 of 19 members thought inflation uncertainty is higher. And 15 thought inflation risks are “weighted to the upside”. These are big shifts from their September projections, as you can see below.

Back in December, Powell was reluctant to admit this shift was because of tariffs and deficit spending by the incoming administration. However, he readily admitted it last week after their January meeting (and it did come out more in the minutes). Powell pointed out that there is elevated uncertainty due to significant policy shifts, from tariffs, immigration restrictions, fiscal policy (deficits), regulatory policy.

Trump’s actions this weekend suggest they were right to worry. Fed members’ statements after the tariff announcements echoed their worries.

Bostic: “I had uncertainty on December 31. The amount of uncertainty that we have today is greater than that.”

Chicago Fed President, Austan Goolsbee: “Now we’ve got to be a little more careful and more prudent of how fast rates could come down because there are risks that inflation is about to start kicking back up again.”

Boston Fed President, Susan Collins: “The kind of broad-based tariffs that were announced over the weekend, one would expect to have an impact on prices,”

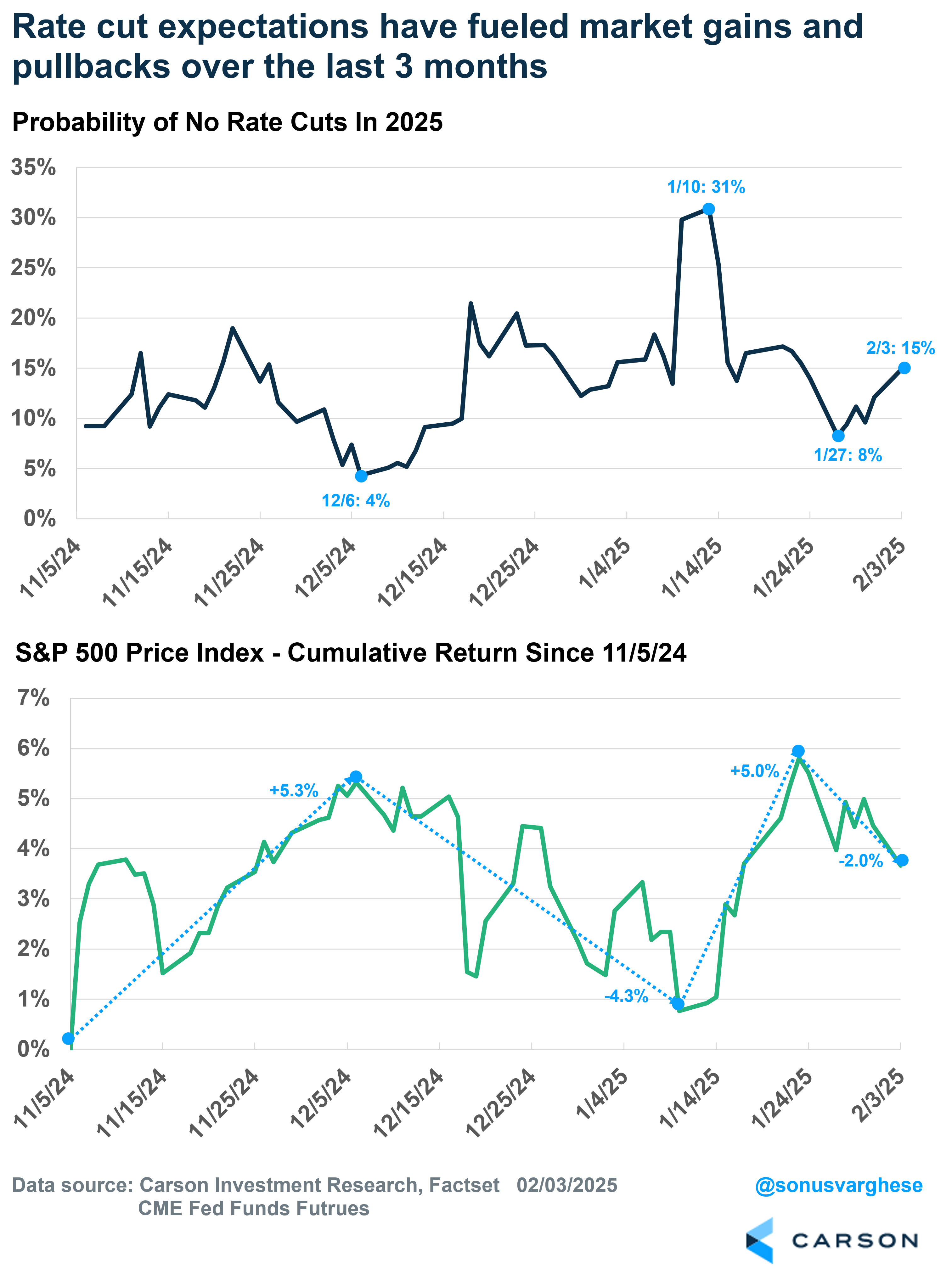

Yes, the tariffs were pulled back, but for now, it’s temporary. Ongoing uncertainty for Fed members may start to increase the probability of no cuts at all in 2025, a potential headwind for risk assets. Just look at the last three months: equity markets have moved in tandem with the probability of no rate cuts in 2025 (as priced by fed funds futures).

- From November 5th through December 6th, the probability of no cuts in 2025 fell from 10% to 4%, i.e. markets were pretty sure of cuts in 2025. The S&P 500 gained over 5%.

- From December 6th through January 10th, the probability of no cuts in 2025 surged to over 30%. The S&P 500 pulled back by 4%.

- From January 10th through January 27th, the probability of no cuts in 2025 fell back below 10%. The S&P 500 gained over 5%.

- Since then (through February 3rd), the probability of no cuts in 2025 has risen to almost 15%, and the S&P 500 has pulled back about 2%.

For now, markets appear to be betting that the inflation outlook looks good, and that we’re still on track for 1-2 cuts in 2025. But this is really the big risk, and likely how tariffs, and uncertainty around them, may impact the stock market over the next several months.

Will Deficit Spending Create A “Get Out of Jail Free” Card?

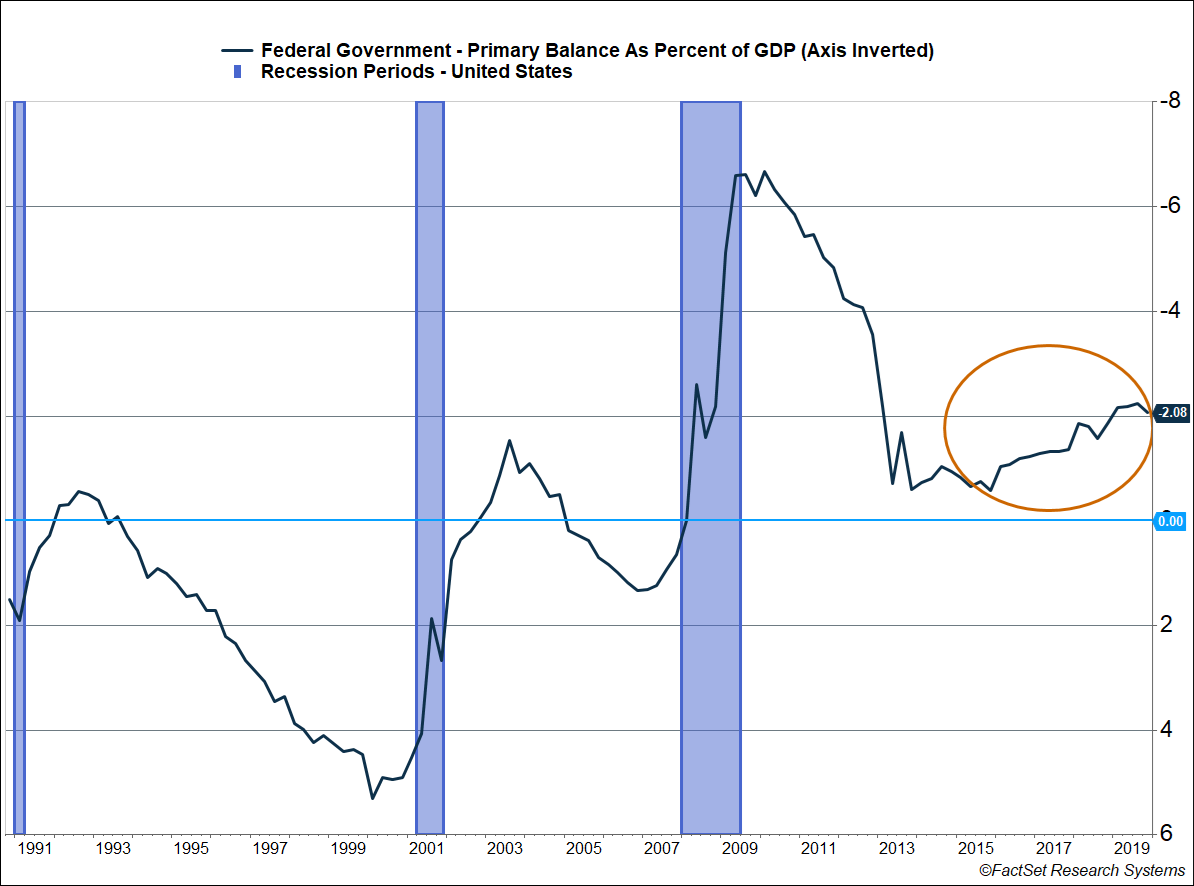

It helps to go back to 2018-2019 to understand this. Deficit spending surged after the Financial Crisis. The primary deficit rose to about 6.5% of GDP (the primary deficit is spending excluding interest payments on debt). However, the deficit started to shrink after 2010, falling to about 0.5% of GDP in 2015. This is historically what happened as economic expansions wore on. Post-recession deficits shrink, and primary balances eventually head into a surplus. But the late 2010s were an exception. A big increase in federal spending, and lower revenue on the back of the 2017 tax cuts, sent the deficit higher. The primary deficit grew to about 2.1% of GDP by the end of 2019. Just from 2018 through 2019, the primary deficit grew by 70 bps, from 1.4% to 2.1% of GDP. As you can see from the chart below, these deficits were completely outside the historical norm. In both the 1990s and 2000s, the primary balance eventually became a surplus.

Deficits provided a big boost to the economy in 2018-‘19, despite the trade war. Real GDP grew 2.7% annualized over the two years, above the 2.4% trend growth. A big part of this was fiscal spending, with government spending rising 3.3% annualized over that period (reversing close to half a decade of austerity). Tax cuts also pushed investment spending up in 2018, though it eased in 2019 amid the trade war (especially structures and equipment investments).

Can government spending more than offset any headwind from tariffs this time as well?

The short answer is yes, but I predict a couple of hurdles. One is that fiscal spending has to be authorized by Congress, and Republicans don’t have a lot of room to maneuver in Congress given their narrow majority in the House. Republicans in Congress are working on a large tax policy package. This will be needed simply to avoid tax increases on January 1st, 2026, when several provisions of the 2017 tax cuts sunset. But they’re also planning additional tax cuts, including a further reduction of the corporate tax rate from 21% to 15%, amongst other measures.

In my opinion, the tax package is likely to pass, but we may have to wait a while for clarity on provisions, let alone the amount by which it’ll increase the deficit. And then of course, final passage.

The second hurdle is that the deficit is already really large. The primary deficit is close to 3% of GDP. Once you include interest payments on debt, it’s about 6% of GDP (thanks to high interest rates). That’s going to be an issue for two sets of people: 1) members of Congress who still care about the deficit (a rarity, but still), and 2) the Fed, who’ll be worried about its inflationary impact. A big deficit-busting package may result in the Fed sitting on its hands throughout 2025, with no cuts at all. But those deficits may overcome any headwinds from higher interest rates, at least in the near-term.

TLDR or “Too Long, Did Not Read” Version for Those Who Just Want the Takeaway

The proposed tariffs on Canada, Mexico, and China are larger than anything Trump did in his first term. Yes, the tariffs on Canada and Mexico have been paused, but there’s a still a lot of uncertainty. (Will they reach a deal? What are the terms of the deal? Are those terms enforceable? Who verifies?). If anything, there’s an enormous tariff cloud cover that wasn’t there last week, including the prospect of 25% tariffs on Canada and Mexico in a month, 10% across the board tariffs on Chinese imports starting Tuesday, and higher probability of big tariffs on incoming European goods.

The economic and inflationary impact of the tariffs are very unclear, simply because we have no idea of the size of the tariffs that may happen, how other countries will respond or retaliate, and how currencies will move in response. We’re totally in the dark from that perspective, but in some ways, that’s secondary to markets. With respect to the impact on markets, there’re two key aspects.

One is the Fed. The uncertainty is likely to push them into an extended pause. They’re going to want to have a better sense of the impact of tariffs before proceeding with more cuts. If there’s a prolonged delay as the tariff can is kicked down the road, and deals are being worked out, we could even see rate cuts pushed out to 2026, assuming the labor market doesn’t falter or we don’t get some other negative growth shock (something we shouldn’t root for because bad is bad news). That’s not going to be good news for stocks.

The other key is Congress. The economy is likely to see headwinds on housing from higher rates, as well as headwinds to business investment due to tariffs (as in late 2019). But deficit-financed government spending could more than offset these. As we wrote in our 2025 Outlook, opportunities like tax cuts can potentially outweigh threats from tariffs and higher rates. However, the sequencing matters, and now we have the threats coming ahead of opportunities. That’s a recipe for volatility, and something that can sap animal spirits. But we’re barely in the first innings, and there’s a long way to go.

For more content by Sonu Varghese, VP, Global Macro Strategist click here.

7602906-0225-A