Lost in all the consternation over a weak payroll report last week was the fact that we got good productivity data a couple of days before that. Labor productivity rose at an annualized pace of 4.9% in Q3. This is not entirely surprising because we already knew output surged in Q3, and hours worked didn’t change significantly – in short, private sector workers across the economy produced a significantly higher amount of output without significantly increasing the amount of time they worked. However, it has big implications.

Stay on Top of Market Trends

The Carson Investment Research newsletter offers up-to-date market news, analysis and insights. Subscribe today!

"*" indicates required fields

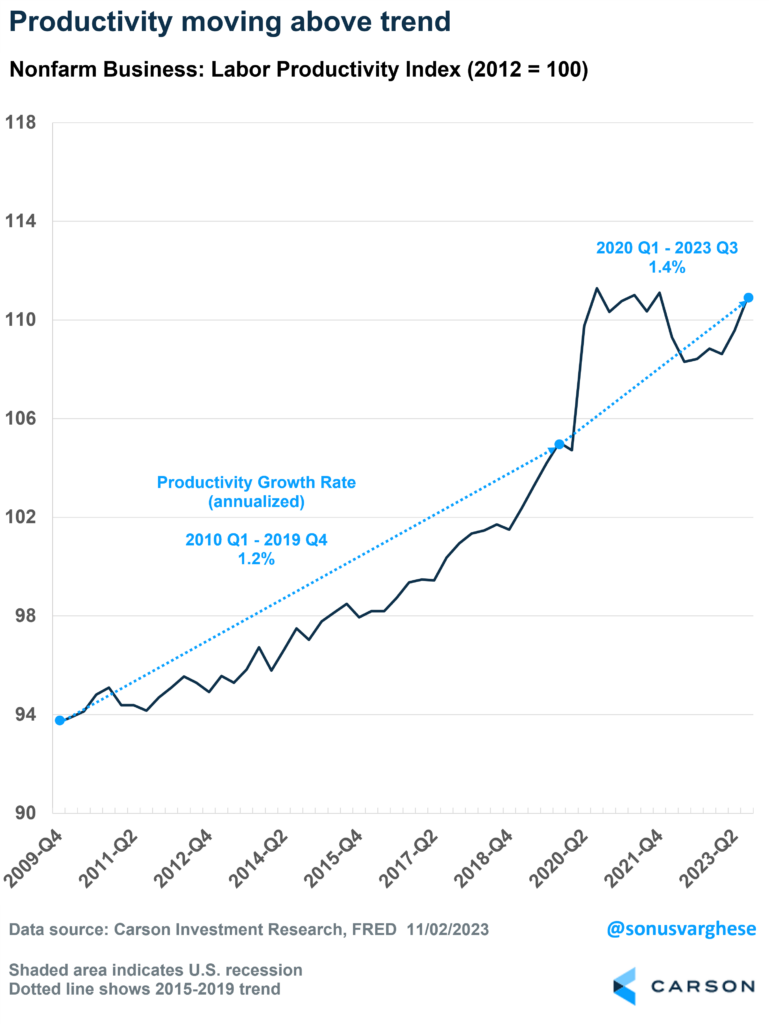

The Q3 blockbuster productivity data follows a hot number from the prior quarter when productivity rose 3.5% (annualized). Quarterly productivity data can be quite noisy so it helps to broaden the horizon. Since 2020, productivity has averaged a 1.4% annual pace, which is faster than the 2010-2019 pace of 1.2%.

Productivity surged after the pandemic hit. Economic output regained its pre-pandemic level by Q1 2021, with 8 million fewer workers – which translated to higher productivity. But this was not because the productive capacity of the economy expanded. Workers can be squeezed for a time to produce more amid downsizing – the same thing has happened amid prior recessions. But it lasts only for so long.

Productivity subsequently fell in 2022, “reversing” the gains from 2020-2021. As workers got hired once again, it looked like productivity was falling. Newly hired workers had to be trained, or re-trained, and periods like these are not great for productivity growth.

But now that the economy is normalizing, the fruits of all the investment over the last couple of years (including labor, which is the business’ largest investment) is bearing fruit, and productivity is accelerating. Over the last two quarters, productivity growth is now running at a 4.1% annualized pace – the fastest two quarter pace outside of recessions and immediate post-recession periods that we’ve seen since the late 1990s.

Higher Productivity Is a Big Deal for the Economy and Inflation

Wage growth for workers is essentially the sum of productivity growth, inflation, and the change in labor’s share of income. Faster wage growth implies:

- Faster productivity growth, or

- Higher inflation, or

- An increase in the share of output going to labor (instead of profits), or

- Some combination of the above

Higher wages can result from higher productivity by any number of ways, including businesses introducing more machines, or organizing work more efficiently. Workers can also be more incentivized to be more efficient. Higher wages can also force less productive firms out of business, raising overall productivity across the economy.

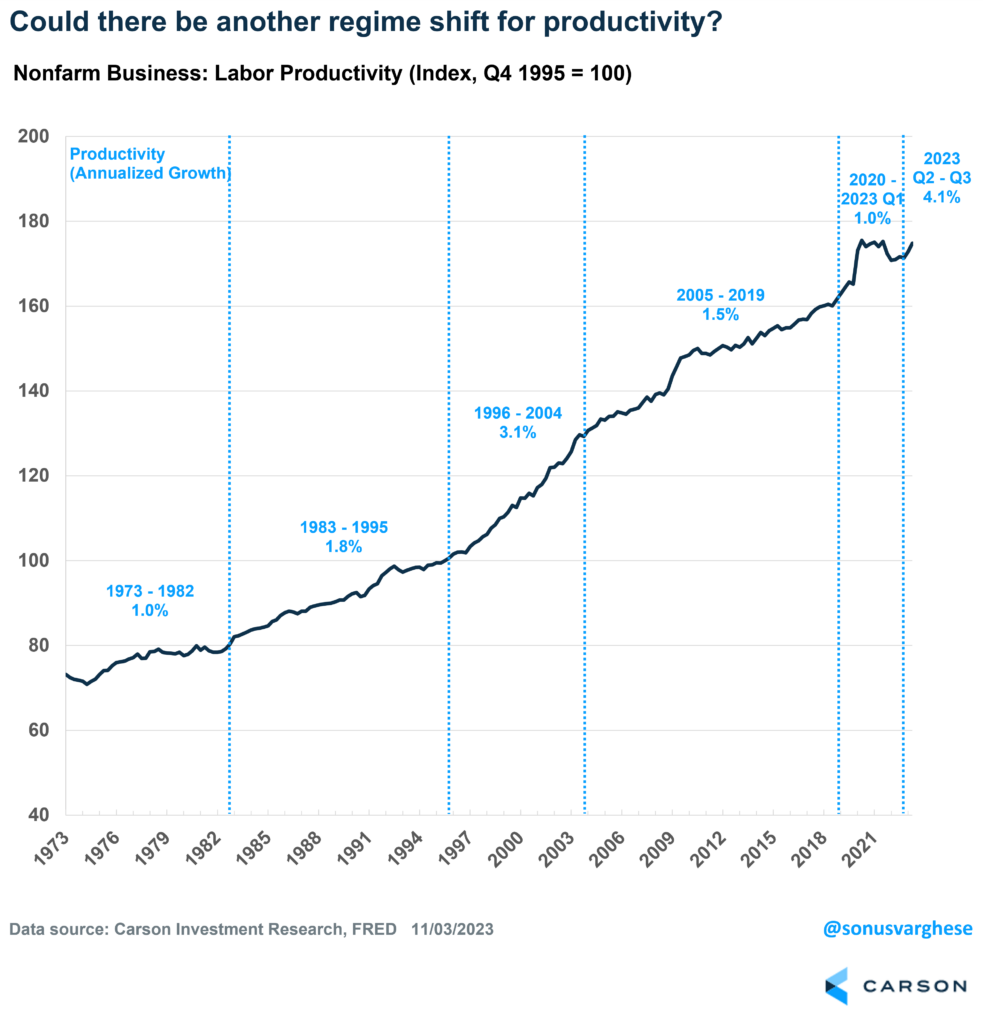

The relationship between wages, productivity, and inflation is probably best illustrated by looking back to history. Here’s a chart of productivity starting in the 1970s on, broken into various periods. I want to focus on two periods in particular: 1973-1982 and 1996-2004.

Wage growth ran at an annualized pace of 8.9% between 1973 and 1982. However, that didn’t translate to productivity increases, which rose at an annual pace of just 1%. Instead, businesses passed on higher costs in the form of higher prices, and inflation averaged 8.2% a year! A big reason for low productivity in the 1970s was the entry of a massive cohort of baby boomers into the workforce, and as I pointed out above, these sort of surges in hiring aren’t great for productivity.

Fast forward to 1996 and we started to see a surge in productivity. Wage growth ran at a 4.5% annual pace between 1996 and 2004. However, inflation averaged just 2.4%, translating to significant growth in inflation-adjusted incomes. This was because productivity surged to a 3.1% annual pace during that period.

A Positive Feedback Loop: Policy and Productivity

As you saw, productivity surged in the late 1990s, so we got solid wage growth with low inflation. Crucially, it could also result in a positive feedback loop between policy and productivity. Strong productivity growth that is accompanied by low inflation could lead to more expansionary monetary policy. That could lead to greater investment and a “tighter” labor market with low unemployment and faster wage growth. This could in turn fuel further productivity growth, and signal to the central bank that they can keep rates low.

This is essentially what happened in 1995, with then Fed Chair Alan Greenspan choosing to reduce interest rates despite strong wage growth. He bet that productivity would increase due to technological breakthroughs, and he was right. Part of it was also because expansionary policy led to tight labor markets that boosted productivity further.

We could potentially be in a similar situation right now, with tight labor markets leading to productivity gains rather than inflation.

Of course, there is a risk that the reverse could happen, with overly tight monetary policy leading to falling investment, more unemployment, and slower wage growth which in turn leads to lower productivity growth.

The good news is that the Powell-led Fed no longer seems to believe that a recession, and sharply rising unemployment, is required for inflation to fall. They’ve watched inflation fall over the past year even as real economic growth has accelerated, and unemployment stayed low. Powell noted last week that there’s a risk of “doing too much”, and unnecessarily sending the economy into a recession. That’s a big deal since it means we could see policy easing if inflation heads down in a sustainable way – which it could if productivity runs strong.

Another Positive: A Surge in Business Formation

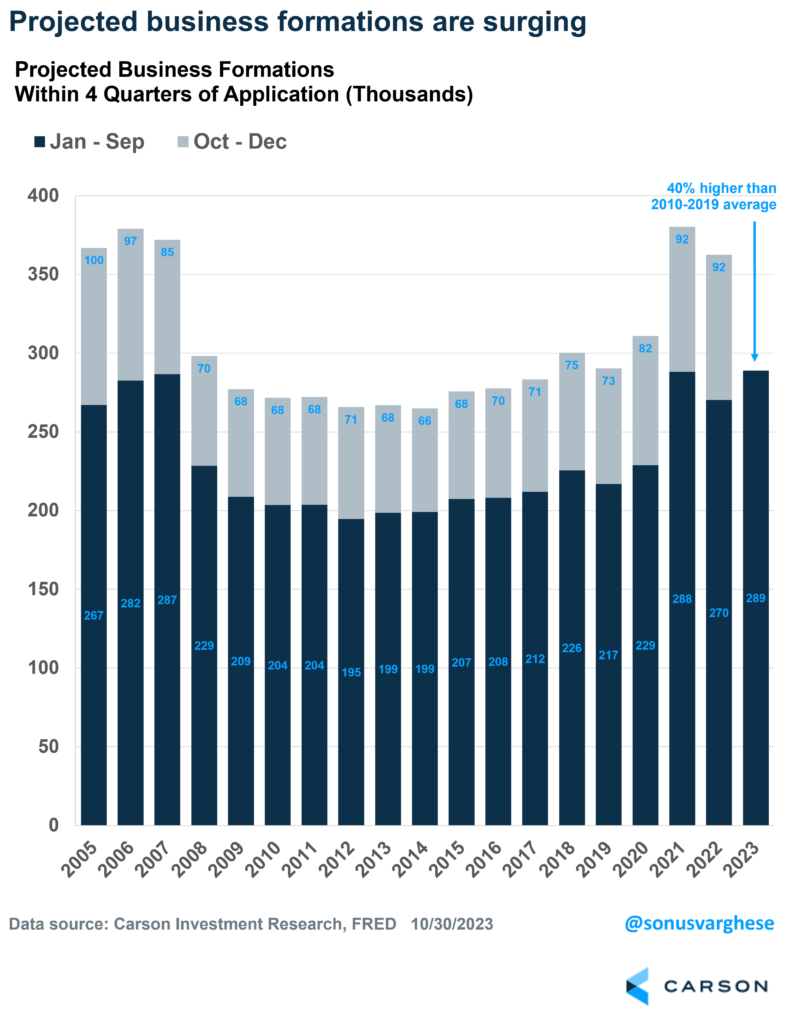

Productivity is highest when a new business is formed and then flattens as the business ages. Without new business formation, productivity is suppressed. The decline in the number of startups in 2014 vs 1980 led a to 3.1% cumulative reduction in productivity for the US economy. Business creation also provides employees with opportunities to switch jobs, for higher pay. To translate that, if this “startup deficit” didn’t occur, real median household income in 2014 would’ve been $1,600 higher, i.e. $66,500 instead of $64,900. The total lost income over the 35 years would be significantly lower!

The good news is that business applications are surging. The Census Bureau measures applications that have a “high propensity” of turning into a business with a payroll, as well as applications that include a first wages-paid date on IRS forms. On a year-to-date basis (Jan-Sep), the Census Bureau’s projection of business formations is running 7% above the same period in 2022. It’s also 40% above the 2010-2019 average, and 4% above the 2005-2007 average.

What About Artificial intelligence (AI)?

AI is certainly an x-factor for productivity. As always, there’s a fear that automation will lead to job losses, but, it can drive cost savings and free workers to do new tasks. As I pointed out above, productivity growth tends to be accompanied by tight labor markets, and higher wages, rather than the other way around.

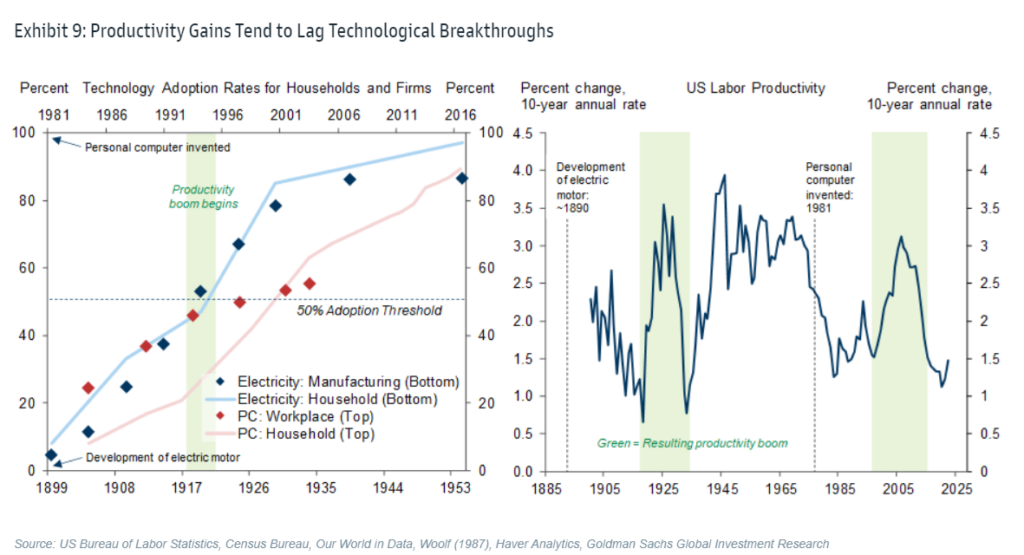

But keep in mind that it can take a while for technological breakthroughs to translate to productivity. Here’s a chart from Goldman showing how productivity booms driven by prior milestone technologies – including motor vehicles and personal computers – lagged the initial innovation by over a decade. They only showed up in the macroeconomic data after half of the impacted businesses had adopted the technology.

Given the speed at which information travels these days, it may take less than a decade for AI adoption to show up in productivity data. Plus, unlike physical automation, AI is “cognitive” automation that can be rolled out via software. As this Brookings study points out, innovation can accelerate as cognitive workers not only produce current output but also invent new things, engage in discoveries, and generate technological progress that boosts future productivity. In addition to R&D, it would also include managers rolling out innovations into production activities across the economy. If cognitive workers are more efficient, they will accelerate technological progress and thereby boost the rate of productivity growth. If productivity growth was 2% a year, improved cognitive efficiency could boost it by 20% – to 2.4%. That’s not much year to year, but these gains compound and it would mean the economy is 5% larger after a decade.

All in all, there’s a lot of reason to believe that the economy could be at an inflection point. A lot of it is riding on policy as well, and how the Fed navigates its policy path over the next year will be critical.

Ryan and I talk about the Fed in our latest Facts vs Feelings episode, and how market moves have been very tied to what’s happening with interest rates. Take a listen below.

For more of Sonu’s thoughts click here: https://www.carsongroup.com/insights/blog/author/svarghese/

1970935-1123-A