An underrated story right now is the US dollar, which has appreciated by over 6% since the end of September. A big driver of the dollar is relative growth rates between the US and everyone else. So, the outlook for the dollar really depends on how you think the US economy will do relative to everyone else. Expectation for stronger economic growth in the US means interest rates are likely to remain high (with the Fed keeping policy rates higher), at least relative to other countries. That means interest rate differentials are likely to run high, driving the dollar higher. The idea is this: if interest rates are much higher in country A vs country B, money will flow into country A, thus raising the value of country A’s currency.

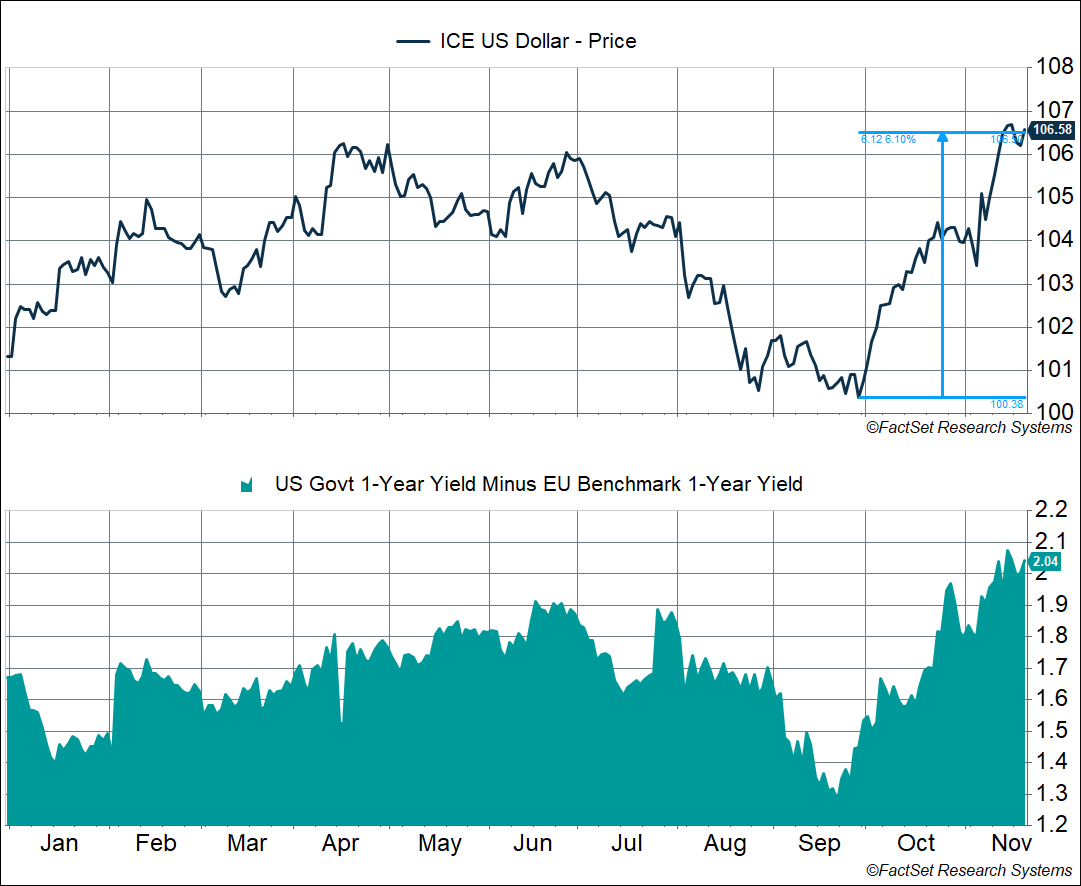

Since the end of September, US economic data has come in much more positive, and recission odds have plunged. This has resulted in lower rate cut expectations, driving longer-term yields higher. At the same time, growth outside the US is expected to remain weak, and foreign central banks are expected to cut rates more aggressively. This has widened interest rate differentials between the US and abroad, driving the dollar higher. The chart below shows the dollar (top panel) and the difference between 1-year US Treasury yield and 1-year Eurozone government yield (bottom panel).

Tariff Front-Running

At the same time, part of the recent dollar surge occurred post-election, a potential front-running of tariffs. A stronger dollar could offset some of the price increases associated with tariffs. Tariffs have a one-time price level effect, i.e. it raises prices after it’s implemented, but not after that (assuming there’s no continuous ratcheting up of tariffs).

Stay on Top of Market Trends

The Carson Investment Research newsletter offers up-to-date market news, analysis and insights. Subscribe today!

"*" indicates required fields

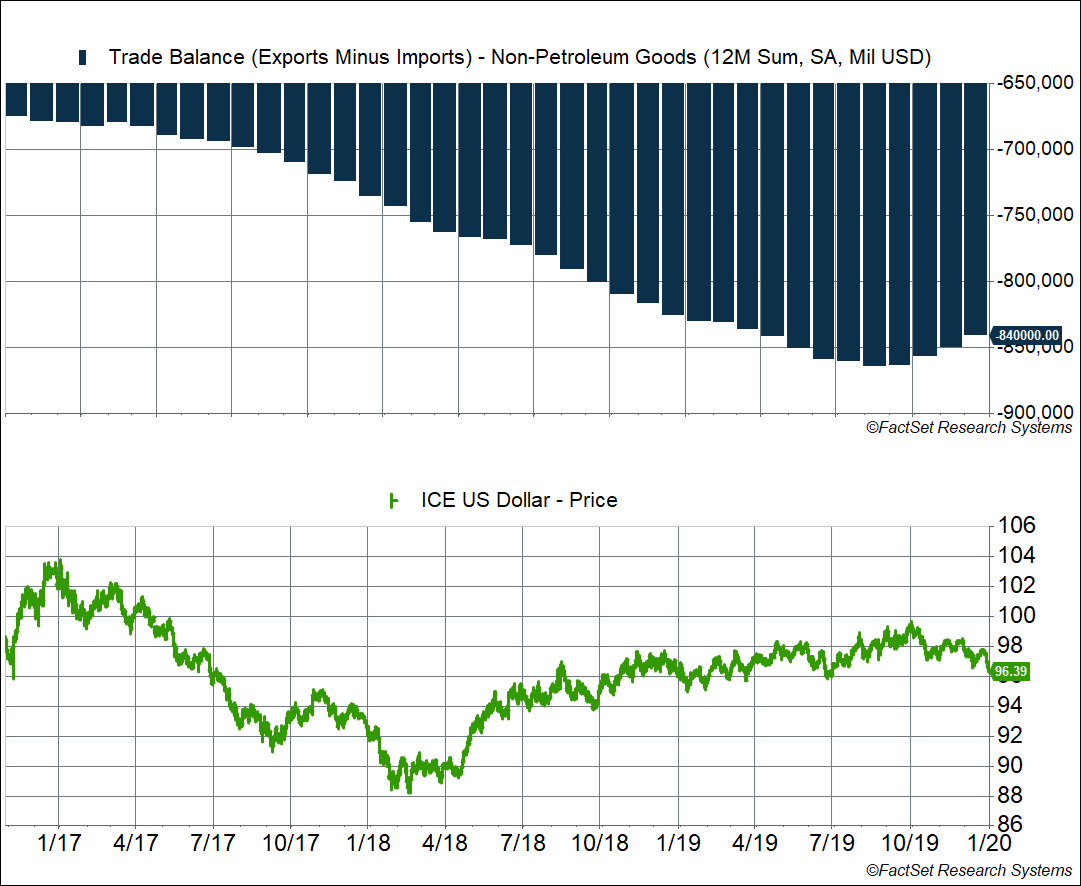

Looking back, the dollar appreciated soon after Trump’s 2016 election, but then pulled back in 2017 as the focus shifted from tariffs to tax cuts and developed economies around the world started seeing stronger economic data amid a manufacturing upswing. China was also stimulating its economy during this period. But the dollar resumed its increase in 2018-2019 amid the trade war. The strong dollar ended up making imports cheaper even as the trade war was raging in 2018-2019. At the same time, it made exports more expensive. The non-petroleum goods deficit rose by 24% between 2017 and 2019.

A Strong Dollar Poses 3 Key Risks

One: A strong dollar hurts US manufacturing

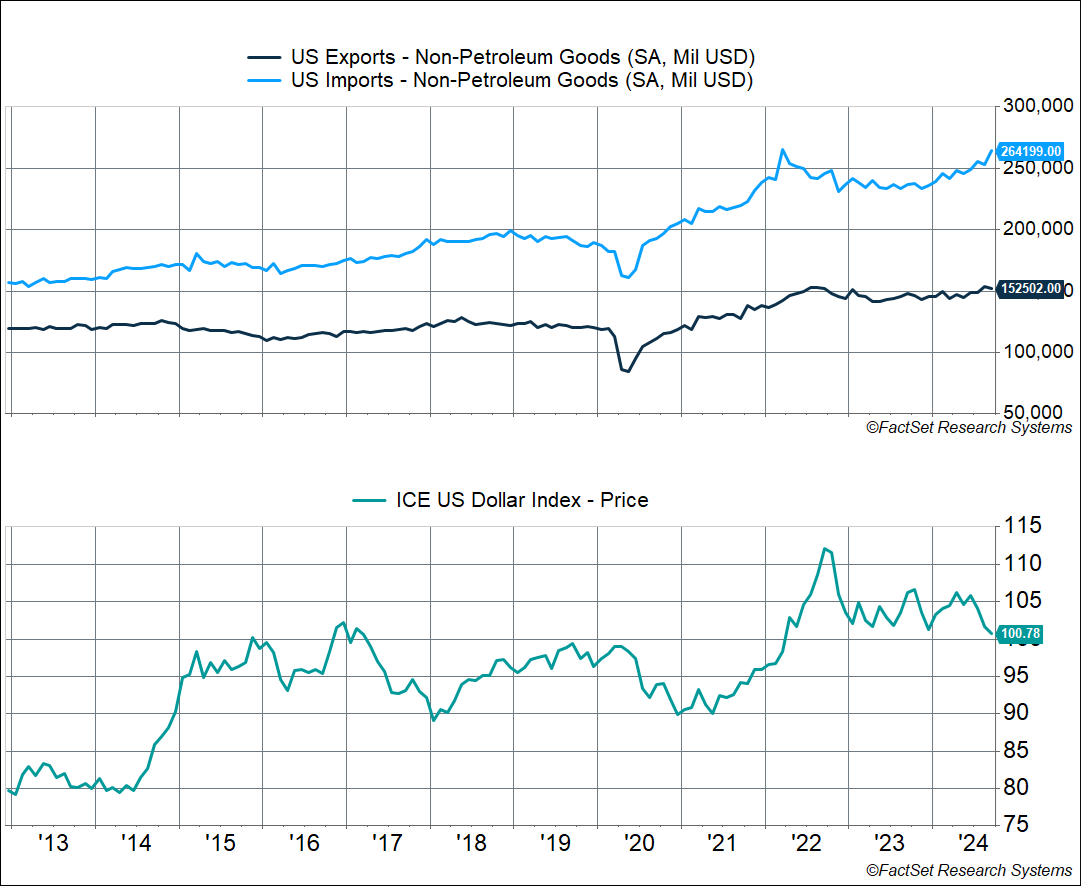

A strong dollar makes American goods more expensive for foreigners. A strong economy by itself is going to pull in imports, more so if these imports are cheaper because of a strong dollar. This is what happened over the last 2 years – non-petroleum goods imports are up 8% from two years ago. However, a strong dollar, along with global weakness, has led to a complete flat-lining of US exports – non-petroleum exports are flat relative to two years ago. As a result, the non-petroleum trade balance has continued to rise, clocking in around a massive $1.2 trillion over the last twelve months.

The last period of broad dollar strength was 2014-2019. This was a period when nominal GDP grew by 27%, and imports grew by 19% (imports would likely have been more in-line with GDP, if not for the pullback in 2019 amid the trade war). However, exports grew just 1% during this time.

Tax cuts in 2025 could offset any tariffs and widen the deficit. That’s likely to raise imports, on balance. However, the stronger US dollar could limit US exports (along with potential retaliation from trade partners). Keep in mind that bilateral tariffs (e.g. against China) may simply result in trade being shifted to other countries – something we saw in 2018-2019.

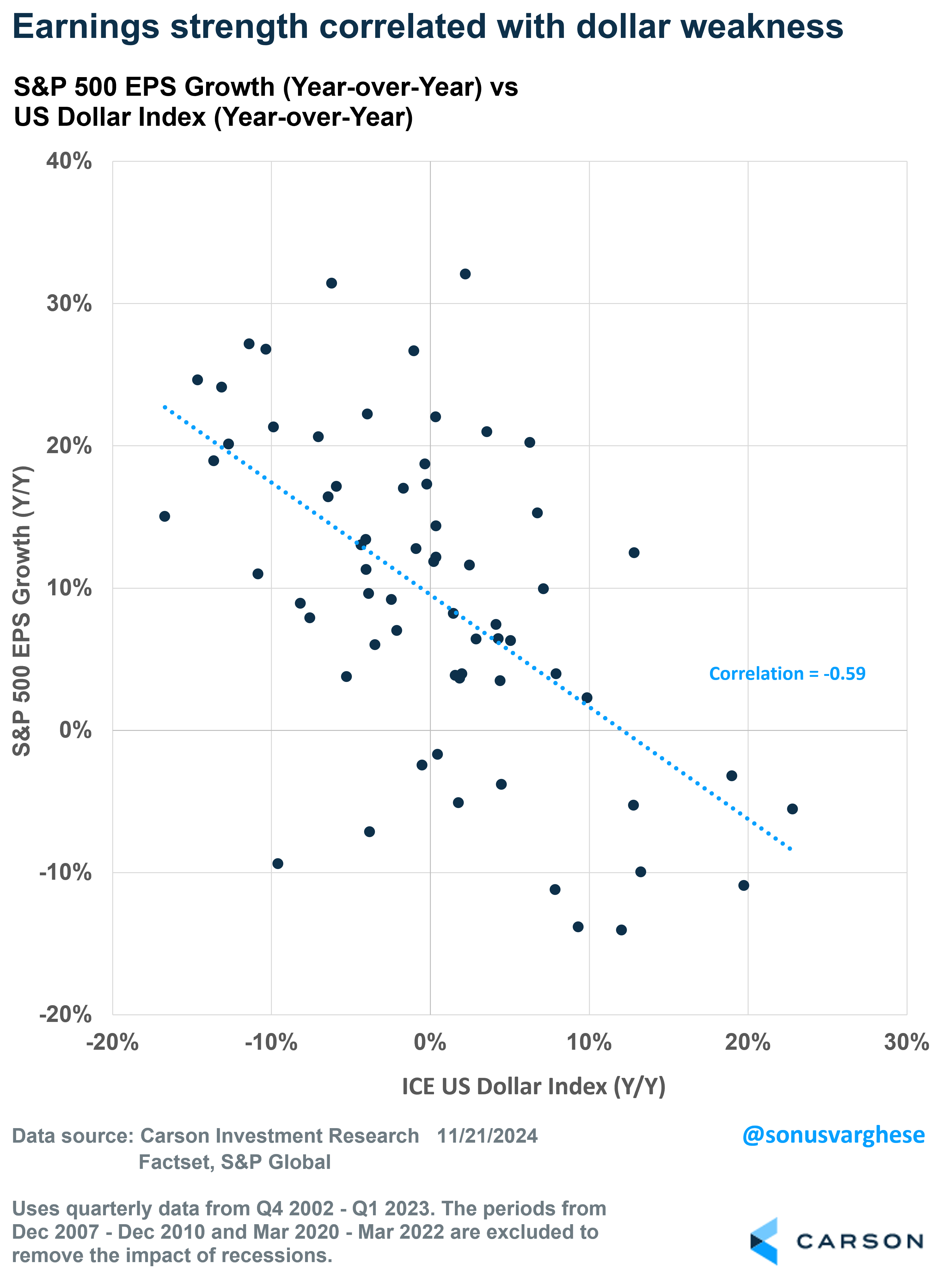

Two: A strong dollar is a headwind for US company earnings

Just over 40% of S&P 500 revenues come from outside the US, which means companies are exposed to currency risk. A stronger dollar tends to reduce revenues (and profits) generated outside the US, and vice versa. Historically, S&P 500 earnings growth outside of recessions has a strong negative correlation of -59% to changes in the US dollar. The chart below illustrates this, showing the relationship from 2022 onwards (which is when globalization really took off). I excluded recessions and their immediate aftermath because the dollar usually climbs during these periods, amid a flight to safety.

On the other hand, dollar weakness has historically seen a big boost to S&P 500 earnings, with 2017 being a good example. The dollar fell by 10% in 2017, amid a surprise pickup in international growth, both of which helped S&P 500 EPS grow by 21%.

Three: A strong dollar is a headwind for international equities

The math for international equities is hard. Consider two investments:

- Stock A with returns of 20% in year 1 and 20% in year 2

- Stock B with returns of 50% in year 1 and -10% in year 2

Both assets have an average return of 20%. But the compounded returns are quite different:

- Stock A: (1 + 0.20) x (1 + 0.20) – 1 = 44%

- Stock B: (1 + 0.50) x (1 – 0.10) – 1 = 35%

The compounded return for stock B is lower because of the “volatility drag.” This also gets to the reason why you always want to reduce portfolio volatility.

The currency impact works similarly.

Say an international equity basket appreciates 30% in local currency terms, but the currency depreciates 15% against the USD. The USD return is not 30 – 15 = 15%. Instead, it’s 10.5%. There are 3 pieces to understand here:

- The investor made 30% on their actual international equity investment

- They lost 15% on the currency

- But, they also lost 15% of the 30% equity gain = 4.5% (the “geometric piece”)

Combining the three pieces, we get 30% – 15% – 4.5% = 10.5%

All of which means, you need to get two pieces right when investing in international equities: the direction of the equity basket AND the USD vs. local currency

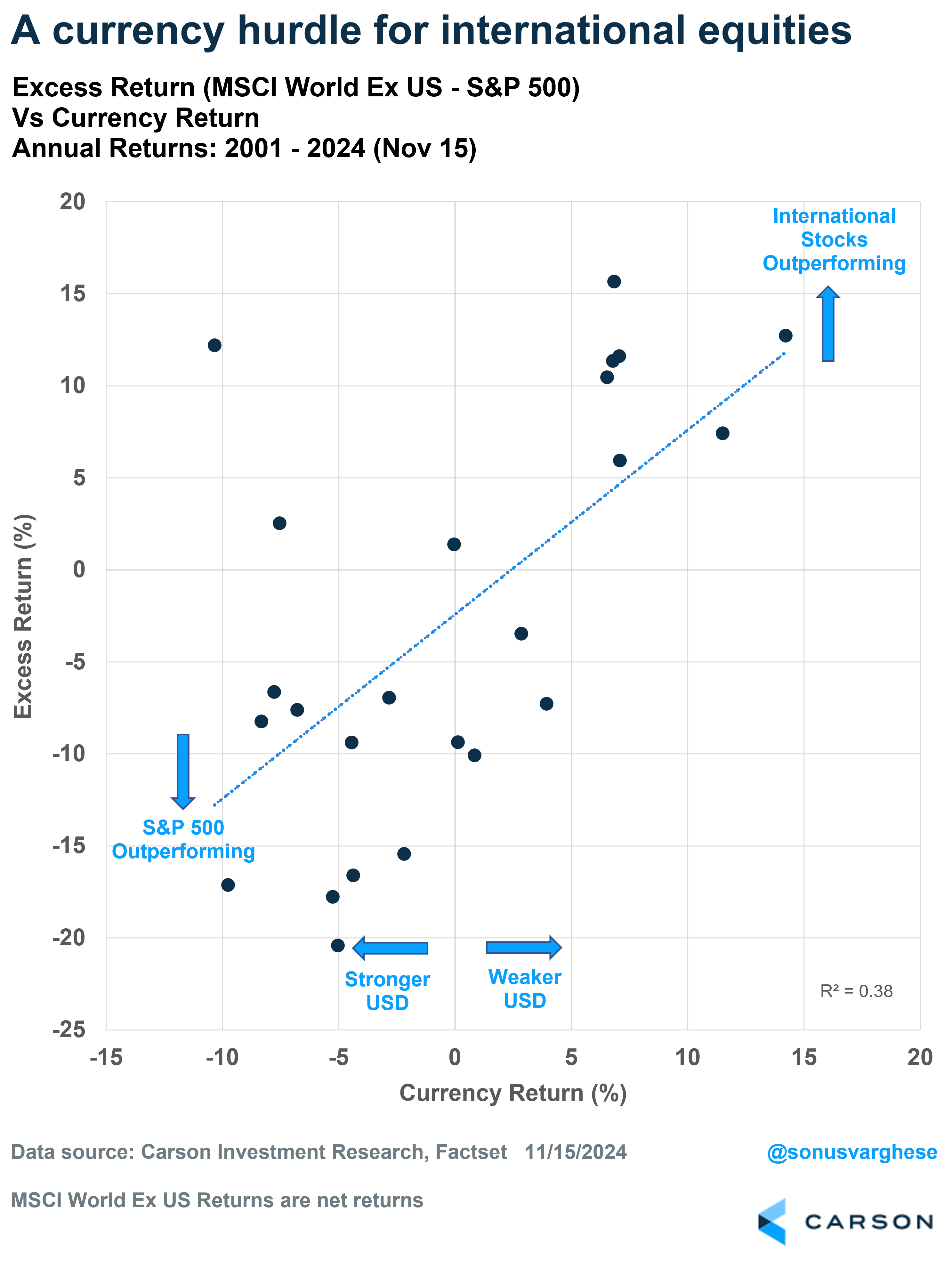

The data bears this out as well. The chart below shows the past 24 years of excess returns for the MSCI World Ex US Index against the S&P 500, versus currency returns. You can see that international market excess returns are typically negative, i.e., US equities outperform when the USD appreciates. And vice versa

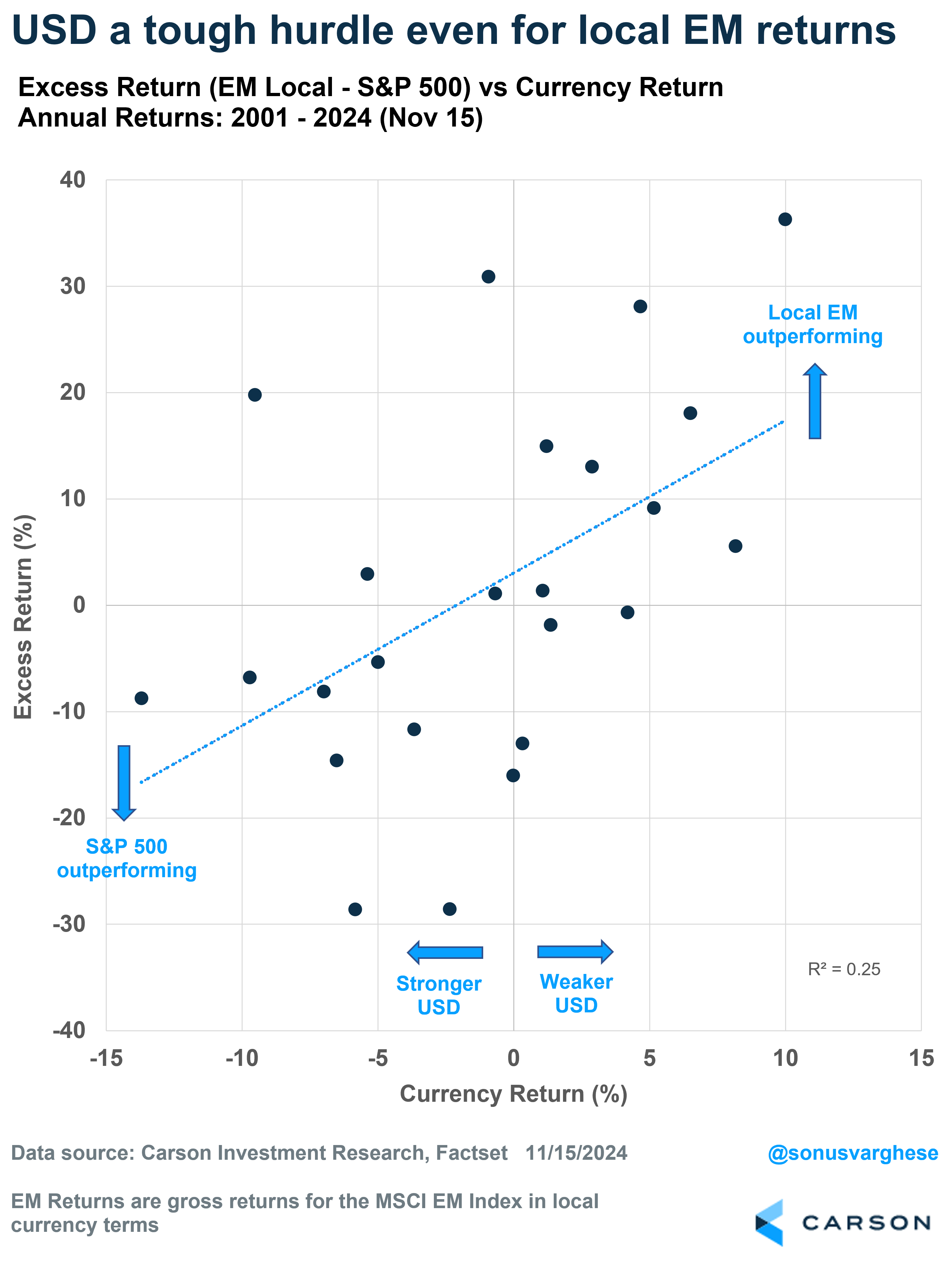

This dynamic is even stronger for Emerging Markets (EM). Part of the reason is that EM local returns are also disadvantaged by a stronger dollar. Normally, you would expect emerging countries to be advantaged by a weaker currency – since it makes their exports cheap in international markets, boosting demand for those goods and stimulating domestic activity.

However, it turns out there’s a financial channel that offsets the trade impact. A weaker currency can lead to tighter domestic financial conditions. A lot of EM companies borrow in US dollars (since it’s cheaper to do so). But their revenues tend to be in local currency. When the dollar appreciates, it increases their debt service costs relative to revenue, thus creating a tougher domestic economic environment. So, a strong dollar is a double whammy for EM equities.

None of this implies that the dollar is going to continue its recent surge. In fact, if growth optimism pulls back a bit, and interest rates follow, the dollar could fall. Even more so if we get a positive surprise on economic data from abroad. However, there’s considerable uncertainty around all of these variables. And even if the dollar doesn’t fall, the current level may be too strong to stimulate manufacturing, especially if rates stay on the higher side. As in 2019, that’s unlikely to throw the economy into a recession, but it’s a headwind.

At the end of the day, we’re still optimistic about US economic growth, much more so than growth abroad, which is why we’re overweight US equities and underweight international equities (especially emerging markets).

For more content by Sonu Varghese, VP, Global Macro Strategist click here.

02521461-1124-A