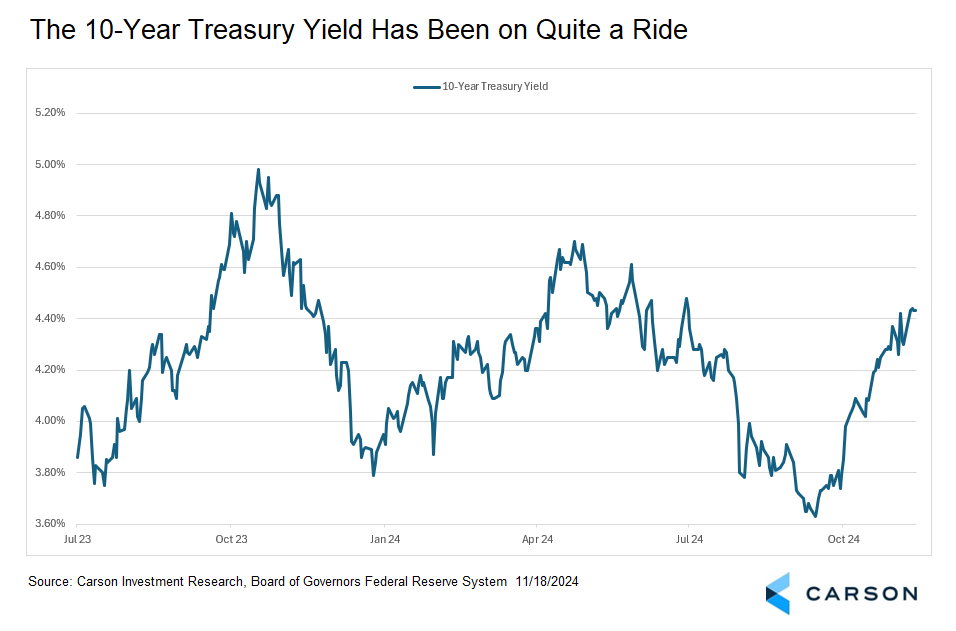

As investors look ahead to the post-election rate environment next year, there are a lot of questions, especially with the recent sharp rise in the 10-year Treasury yield. Like 2023, when interest rates started and ended the year in the same place with a whole lot happening in between, interest rates have been on quite a ride this year. Despite the Fed cutting rates, we’ve seen a vicious rise in Treasury yields the last couple of months. As shown below, the 10-year Treasury yield peaked for the year (to date) way back on April 25 at 4.71% as stubborn inflation and strong employment numbers delayed Fed rate cuts. It then bottomed at 3.62% on September 16 as the disinflation narrative took hold again, the unemployment rate started to rise, and markets increasingly anticipated a more aggressive path of rate cuts. (The Fed cut rates 0.5% on September 18.) As of close on Monday, we are back up to 4.41%, a 0.79%-point increase in about two months.

But that’s the past. Investors are more interested in what’s going to happen moving forward. Here’s the short version of what we’re thinking right now. With the help of pro-growth policy on both the fiscal side (think the president and Congress) and the monetary side (think the Federal Reserve), there’s very good reason to think we’ll see solid economic growth in 2025. (Take a look at Carson Global Strategist Sonu Varghese’s recent blogs, “The Economic Outlook Looks Pretty Good,” Part 1 and Part 2 for a deeper dive into our views.) For reasons discussed below, despite a good growth picture, it’s unlikely to be outstanding. In fact, markets are probably pricing in growth a little too aggressively right now.

Stay on Top of Market Trends

The Carson Investment Research newsletter offers up-to-date market news, analysis and insights. Subscribe today!

"*" indicates required fields

The range of inflation outcomes is even more uncertain. We think if inflation is going to be a problem it’s more likely a 2026 issue, especially with shelter inflation still catching up with much lower real-time data. (See Sonu’s most recent thoughts on inflation here.) Solid growth with inflation holding generally steady means the Fed will cut rates but will see little reason to be aggressive. That probably means perhaps some downside pressure on rates from here, but you can roughly take your bond yield as your baseline return. As of Monday’s close, that’s 4.84% for the Bloomberg US Aggregate Bond Index (Agg). Any decline in yields and you’ll do better (and any increase and you’ll do worse). We show some return scenarios for yield changes in both long- and short-term yields below.

Even 4.84% would be a pretty good return for bonds (but we think stocks are still meaningfully more attractive). Just getting the yield would provide a return about a percentage point above the annual return for the Agg from 2001 – 2023 of 3.73%. Even though it’s a good number, short-term yields remain competitive. But that will continue to fade as the Federal Reserve (Fed) lowers interest rates making longer maturity bonds increasingly attractive, increasing demand, which helps lower yields. In fact, we think we’re likely to see the three-month Treasury yield “uninvert” (move below) the 10-year Treasury yield by the end of next year.

That’s the big picture. Let’s take a look on why the base case for the scenario analysis is where it is, which is based on about a 0.5%-point decline in the 10-year Treasury yield.

Three Reasons the 10-Year Treasury Yield May Be Around 4% in a Year

Reason 1 – Yields

Yields can move around a lot, but they tend to be relatively stable in the big picture, although there are certainly important exceptions. Sure, we can see yields generally climbing from the early 1960s to 1981 and then generally declining through 2020 (with a whole lot of noise in between), but those movements are quite slow. If you wanted to make an extremely rough estimate for yields, start with about where you are now and then start making adjustments for current factors in play. Since yields have been moving around, if you average the top and the bottom of the range since mid-September, you get … about 4%.

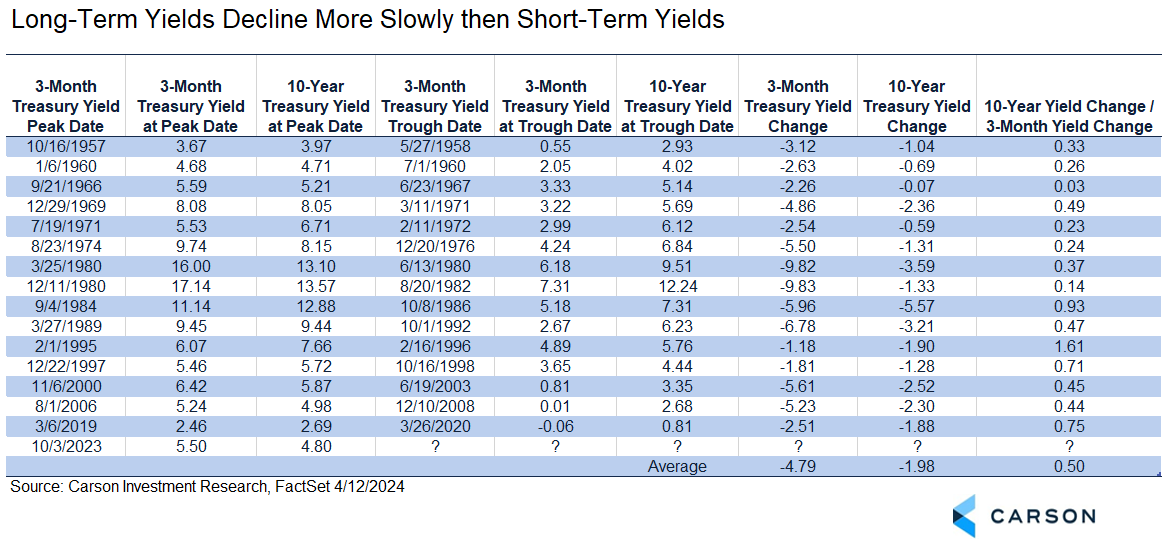

Reason 2 – Rate Cuts

During major historical declines in short-term yield due to Fed rate cuts, the 10-year Treasury yield has fallen about half as far as short-term yields, although there’s a lot of variation. If you expect the Fed to cut about four times over the next year, you would on average expect a 0.50%-point decline in the 10-year Treasury yield. That would leave you at … about 4%.

Reason 3 – Good but not Great Growth with Stable Inflation

Here’s the most complicated one. We do expect growth to be good over the next year, which should be positive for equity markets in particular. If there’s any wisdom to the old saying, “Don’t fight the Fed,” there’s even more wisdom to “Don’t fight the Fed and Congress.” For 2025, at least, even the anticipation of pro-growth policy will help put a floor under growth. It should be a pretty good year.

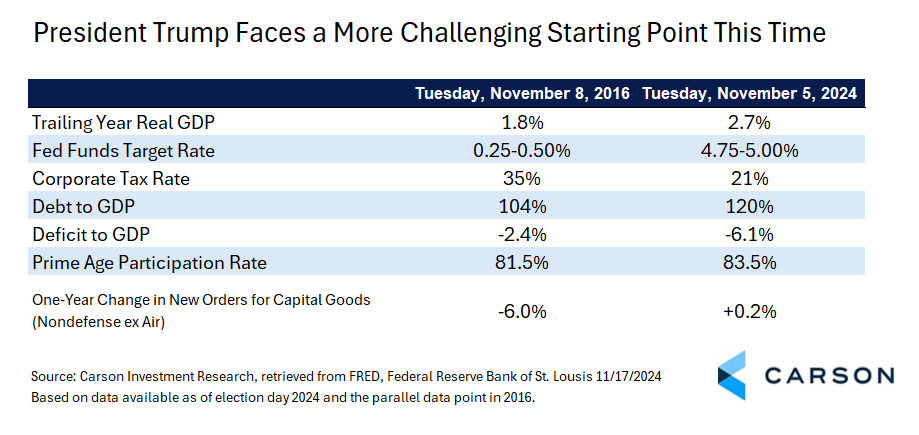

But, as the table below shows, this isn’t 2016. During President Trump’s first term there was a nice springboard for growth in place as he assumed office. In fact, global manufacturing was on an upswing in 2017. That’s not the case anymore. That’s doesn’t mean we’re going to have a bad year. It just means we’re unlikely to have a great year. Jumping off that springboard in 2016, four-quarter real GDP growth initially peaked at 3.3% in the four quarters ending in Q2 2018. It then slowed somewhat, but then reaccelerated to 3.4% in the four quarters ending Q4 2019. But conditions aren’t the same right now. Here are some key comparisons.

The most important of these is probably the interest rate environment. Rate cuts will support growth, potentially bringing some pent-up loan demand back into the market, but the level matters too. Interest rates were still ultra-low when Trump started his first term. The Fed had hiked rates at their last meeting of 2015 and once more a year later at the last meeting of 2016 after the election, bringing the target range to 0.50–0.75% when Trump took office. As the economy improved, the Fed began to normalize rates, the fed funds target reaching 2.00 – 2.50%. But as President Trump argued correctly at the time, the economy was not strong enough to absorb hikes to that level, and the Fed had to initiate a mid-cycle adjustment of a modest number of cuts.

Fast forward to today. Even with rates well above the 2019 peak, the economy has been incredibly resilient, with the adverse impact of elevated rates seen most strongly in housing, manufacturing, and among small businesses. The Fed has cut rates once since the election and the target range is currently at 4.50-4.75%. In other words, it would take nine cuts just to get the economy to the point where rates were considered too restrictive in 2019. We believe the Fed should continue to cut rates, but if the economic growth remains fairly strong, as we expect, we’ll probably only see 3-5 more cuts by the end of 2025.

The absence of a springboard means we’re unlikely to see real growth accelerate to 3.3% this time. Acceleration to 3.0% would still be very good and an upside surprise. Even maintaining the current 2.7% would be quite good. In fact, even a modest slowdown to 2.5% would be solid given the environment. (The median projection for 2025 real growth in the Fed’s last Summary of Economic Projections was 2.0%, with the highest projection at 2.4 – 2.5%. Note that this came out in September, before the election.)

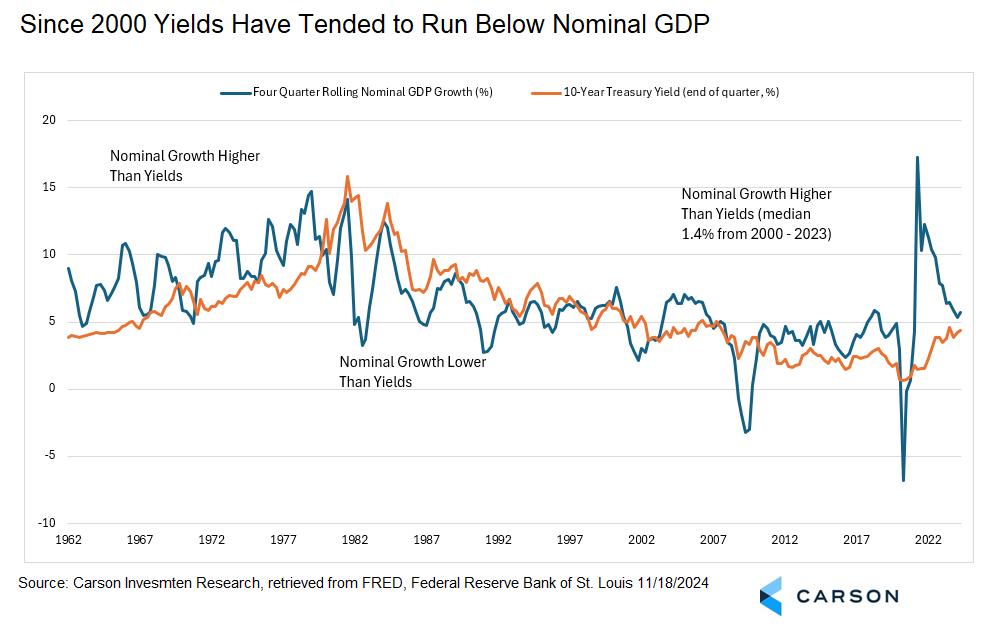

So what does that mean for rates? Since 2000, the 10-year Treasury yield has run at a median of 1.4%-points below nominal GDP. That’s across a number of different environments but outside recessions it’s been fairly consistent and may partly have been due to the negative correlation between stocks and bonds (so there was more demand for treasuries). Since that’s for nominal GDP, we need to add back inflation to real growth estimates. Let’s take the bullish scenario of 3% real growth and the Fed’s inflation expectation in the September projections of 2.1% for 2025. We’ll add in a small amount of upside risk on inflation to be conservative, call it 0.3%, although as mentioned above we think any policy impact of inflation may be delayed. That gives you an aggressive nominal growth expectation of 5.4%. Take the historical 1.4% median discount to that for the 10-year yield and you get … about 4%.

Obviously a lot can happen in the next year. Making a point estimate for where yields will be is not an exercise in futility, but it’s at least frustration. But it’s still useful to have an “all else equal” estimate as a starting point, and a framework for thinking about it as I laid out above. After that, we’ll need to follow the data.

What does that mean for investors? We still think it’s ok to maintain a level of interest sensitivity similar to the benchmark Agg right now. In fact, as short-term rates move down it becomes even more desirable. Short-term rates are still attractive, but they’re slowly becoming somewhat less so over time. The 10-year Treasury yield is likely to remain volatile and there’s some uncertainty around inflation in particular, so bond investors will need to have some patience. We think that patience will be rewarded, but we still believe in looking for some risk diversification that may have a different risk profile and economic sensitivities than fixed income.

For more content by Barry Gilbert, VP, Asset Allocation Strategist click here.

02515920-1124-A