The Federal Reserve (Fed) is poised to start the rate cut cycle in September. In his Jackson Hole speech, Fed Chair Powell explicitly said that the “time has come for policy to adjust.” In fact, minutes from the last Fed meeting in July indicated that some members thought the committee should have actually reduced rates last month. This does raise the question markets are currently grappling with: How much will the Fed cut rates by at the September meeting? Right now, there’s a lot of uncertainty around this question, with fed fund futures pricing a 55% probability for a 0.25%-point cut and 45% probability of a 0.5%-point cut. In short, coin toss odds.

At the same time, there seems to be some stubborn inertia on the part of several Fed members. A few of them have said they need to see (yet) more data and are inclined towards moving forward at a gradual pace, implying they believe the Fed ought to cut rates in a slow and steady manner, with a 0.25%-point cut at each meeting.

Investors aren’t quite sure about this. Over the rest of 2024, markets are pricing well over 1%-points of cuts, which would take the fed funds rate from its current 5.25-5.5% range down to 4.25-4.5% The Fed has three meetings left in 2024 – which means investors think the Fed will cut 0.5%-points at one of these meetings. This is likely conditioned on expectations that we may see one or more data points, including employment data, that shows economic growth pulling back.

The Fed Needs to Signal They’re Managing Risk

Powell noted that they will follow the data, but the problem with that is the data shows what happened in the past. It’s akin to driving by looking in the rear-view mirror. On top of that, Powell and others have repeatedly noted over the past few years that monetary policy impacts the economy with “long and variable” lags, which would imply any action they take now will not impact the economy any time soon.

The Fed has two mandates: ensure low and stable inflation, and maximum employment. That means they have two risks to manage:

- the risk of inflation being too high

- the risk of weak employment

Powell pointed out that the balance of these risks has shifted decisively. Upside risks to inflation have diminished and downside risks to employment have increased.

On the inflation front, the latest reading of the Fed’s preferred inflation metric – the Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) Index – shows inflation is muted. A year ago, when the Fed raised rates to 5.5%, core PCE was at 4.2%. That would imply a “real rate” (nominal interest rate minus inflation) of 1.3%. But with core PCE at 2.6% (likely lower, given it’s running at a 1.7% annualized pace over the last three months), the real rate is now about 3%. That’s a significant tightening of monetary policy even though the Fed hasn’t raised rates further – thanks to inflation pulling back. Our friend Neil Dutta, the Head of Economics at Renaissance Macro Research, has been stressing this point for some time now. Note that Fed members think the long-term real rate that is neither too tight nor too loose is 0.8%. We’ve gotten even further away from that this year.

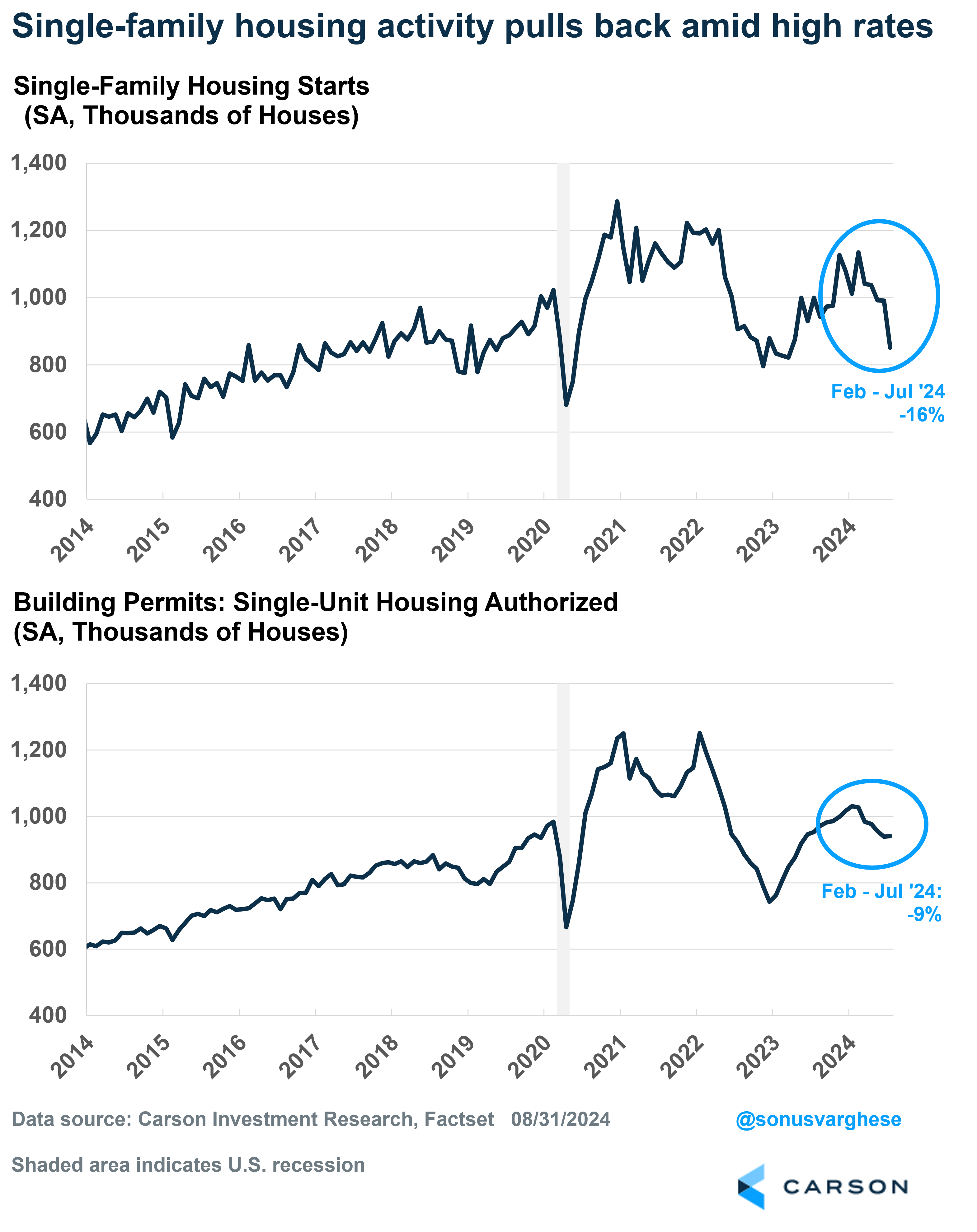

We see the impact of this in several areas of the economy that are dependent on rates, including soft vehicle sales and plateauing capital expenditures by firms. But its most noticeable in housing, where activity is in a clear downtrend. Single-family housing starts have fallen 16% over the last six months. Permits, which are a sign of future supply, have fallen 9%.

Markets have already been anticipating Fed rate cuts, causing interest rates to pull back. 30-year mortgage rates have eased to around 6.4% over the past month, down from over 7% at the end of June. Yet, this hasn’t been enough to boost mortgage applications, let alone builder activity. Builders pulling back could mean we’re going to see fewer homes in the future. Tight policy is also sowing seeds for a future inflation problem. We’ll likely need mortgage rates closer to 6%, if not lower, to see housing activity meaningfully pick up.

A very simple way to think about the adverse impact of higher real rates: Part of the reason inflation has eased is because income growth has pulled back. But with rates remaining on the higher side, it’s gotten harder to afford big ticket items via a car loan or a mortgage.

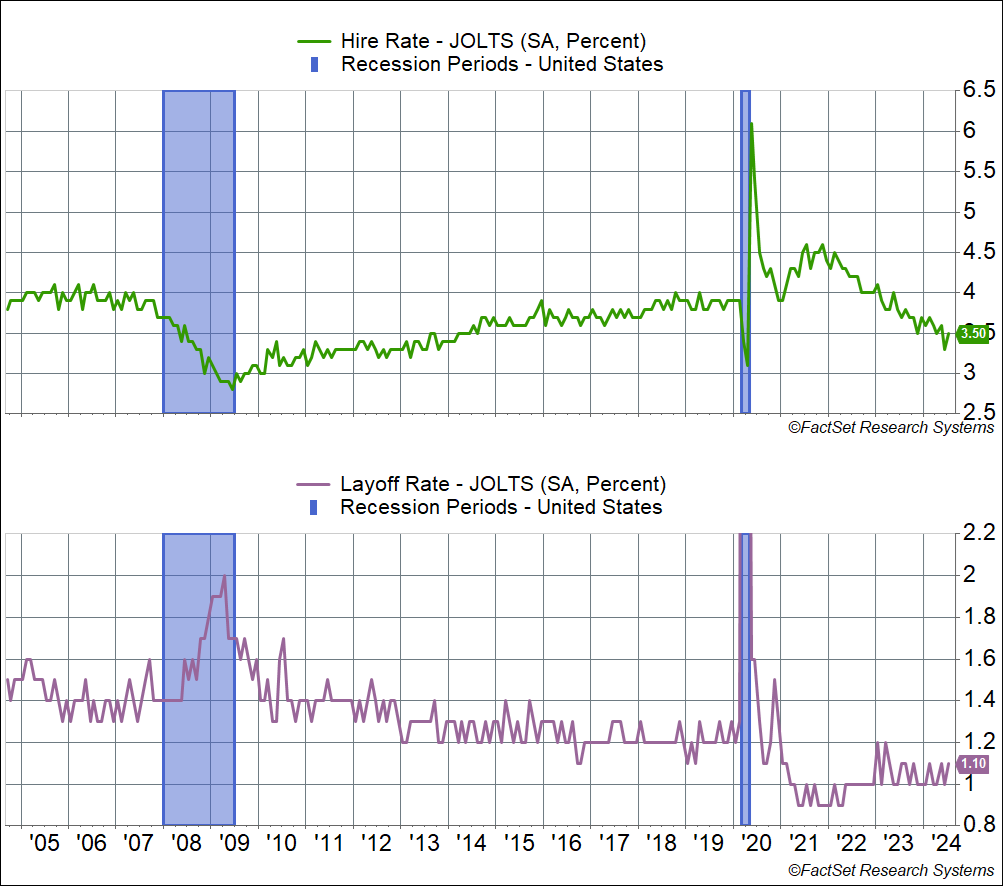

The reason wage growth has eased is because the labor market is softening. The unemployment rate has risen from 3.4% to 4.3% over the past year, and historically, once the unemployment rate starts to rise, it doesn’t stop. Hiring appears to have stalled – the hiring rate, which is hires as a percent of employment, has pulled back to 3.5%. Outside of Covid, that’s a level we last saw in 2014. The good news is that layoffs remain low – the layoff rate, which is layoffs as a percent of employment, is 1.1%, below the 1.2-1.3% rate we saw pre-pandemic. As labor economist Guy Berger points out, it’s hard to find a job now, but there’s relatively low risk of losing one.

The current levels of labor market data do not point to a weak labor market, yet. Even a 4.3% unemployment rate is low relative to history. The problem is the lines are all going in the wrong direction. Labor market weakness, and perhaps ultimately a recession, is a process that builds on itself. There’s no arbitrary threshold for data that defines the entry point of a recession. You don’t want to get to a point where the labor market is too weak to recover without significant help, which is why it’s important for any downtrend to be cut off as early as possible.

This is why the Fed needs to signal serious intentionality that they are not willing to allow further cooling in the labor market. The best way to do that is to go big at the start of their cutting cycle. Otherwise, investors are going to be left guessing whether the Fed is really serious about managing risk on a forward-looking basis. Each economic data point, especially those from the labor market, will take on outsized importance despite the inherent noise in them. We already got a taste of this over the past month. Growth fears picked up after July employment data showed the unemployment rate rising to 4.3%. These fears subsided after more positive data from initial unemployment claims (indicating layoffs remain low). Market pricing for the size of the Fed’s September cut likely rests on the fate of the August unemployment rate, which could tick up or down for any number of reasons.

Stay on Top of Market Trends

The Carson Investment Research newsletter offers up-to-date market news, analysis and insights. Subscribe today!

"*" indicates required fields

The irony is that there comes a point where being data dependent increasingly becomes being noise dependent, until reality is forced on you and you can ignore the data no longer. This happened as inflation was rising, with the Fed ignoring the data by chanting “inflation is transitory” like they were Frank Costanza chanting “serenity now” in Seinfeld. While the goal now is to manage employment risk rather than inflation risk, the potential mistake is the same.

There is a fear that going big will be bad for equities, as it could signal the Fed is panicking and perhaps knows something the rest of us don’t. However, as Dutta put it, it should be clear from the last couple of years (if not decades) that the Fed doesn’t know anything more than the rest of us. Instead, going big will be an indication that they intend to manage risk and get ahead of the data, instead of remaining behind it.

For more content by Sonu Varghese, VP, Global Macro Strategist click here.

02396811-0924-A